|

LEICESTERSHIRE |

|

South Kilworth (Lutterworth) (Nosely) (Old Dalby) Peatling Magna (Prestwold) (Quorn) (Rothley) (Scraptoft) (Shepsted) Skeffington South Kilworth Stapleforth (Thurlaston) (Tilton-on-the-Hill) (Wistow)

| Ashby-de-la-Zouche - St Helen |

|

|

|

| Left: R Nunby ( 1526), incised slab with inscription. Above:Francis Hastings, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon (1561) & Katherine (Pole) (1576). Alabaster effigies and tomb chest. Note the inscription. The couple had eleven children. Below left: Theophilus 6th Earl of Huntingdon (1698), With motives copied from the monument to the 2nd Earl. The upper of the two tablets to the right of the monument records that chapel was restored by the 3rd Baron Donnington (see below) and his wife, Maud Kemble in memory of their two young children: 2nd daughter, Edith Winifred Lelgarde Hastings (1908) and 4th daughter, Alicia Moira Stuarta Hastings. The lower is in memory of Gilbert Theophilus Clifton-Hastings-Campbell, 3rd Baron Donnington (1927). Centre left: Theophilus 9th Earl of Huntingdon (1746), The obelisk was designed by Kent and carved by Joseph Pickford. In front is a large vase with a demi-figure of his widow; by Rysbrack. Centre right: George Rawdon-Hastings, 2nd Marquess of Hastings (1844) Far right: Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings KG PC 1st Marquess of Hastings (1826) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Above: Detail

of the monument of the 9th Earl, showing his widow,

Selina, who has a brass in the chancel floor. Right: Margery White (1623) who gave £42 to provide gowns for the poor of the town. |

| Other Monuments | |

| A Pilgrim (15th century) alabaster effigy; one of only two in England. With staff and wide hat with cockle shells. Said to be the 3rd brother of William Hastings | John Francis Clarence Westenra Hastings, 15th Earl (1990), and his wife, Margaret Lane (1994) Tablet with modest inscription with 'shelf' above holding urn. He was a Labour politician. Wikipedia is in error here and refers to John Francis...etc as the 16th Earl |

|

Slab under arch with foliated cross;

only the head and feet of the figure show.

|

| Belton |

| No to be confused with the Belton in Lincolnshire |

/100_0035.png) |

/100_0004.png) |

/100_0003.png) |

/Resea305.png) |

/100_0022.png) /100_0030.png) /100_0041.png) |

Roseia de Verdun, foundress of Grace Dieu Priory in 1240, from where the monument was moved at the Dissolution. The tomb chest is later but the shafts and canopy surrounding the effigy, which is similar in dress to the Fontevraud effigies, are 13th century. Gray sandstone, much recut, especially the face, but still a beautiful monument |

| Bottesford - St Mary |

| St Mary's has an excellent collection of monuiments. Several of the photographs below are 'group' photographs and there are often no corresponding photograph of the individual monuments. |

|

|

Above in the background from left to

right are: 1.The Fourth Earl. 2.

The Eighth Earl. Note the brass at the base; this is referred to below. 3.

The Fifth Earl 4. William, Lord Roos (1414).

There are two wall tablets between 1 and 2;

these may relate to those listed in Other Monuments

below. And in the foreground are: 1. The Second Earl. 2. The First Earl. |

|

Left: There is an inscription plate to Robert de Ross (1285) & his Wife referring to a hear burial (not shown). This minature, incomplete figure of knight left is said to represent him. Purbeck marble. Above: William, Lord Ross (1414), alabaster knight on a tomb chest with angels. |

1. Lady in wimple, c 1310 - 20, ironstone. This figure can be partly seen in the photograph of the monument to the 3rd Earl, below, on the ground to the left of the monument. 2. John, Lord Ross (1421) Similar to William, left. Shown partly on left of the photograph of the monument to the 6th Earl below 3. George Manners, 7th Earl of Rutland. (1641) He inherited the title from his brother Francis, the 6th Earl. By Grinling Gibbons, the effigy being carved by Quellin. He married Frances (Cary) but she is not shown on the monument. The title was inherited by his second cousin, John. Baroque, standing figure in Roman dress on pedestal. This is shown on the right of the 6th Earl. 4. Henry de Codynton, Rector (1404), brass. Figure with tall canopy. This is probably at the base of the monument to the 8th Earl. 5. John Freeman, Rector in 1420, small & now headless. Sir John Thoroton, architect, (1820), plain tablet. Most of the 18th century monuments were moved to the Belvoir mausoleum. |

||

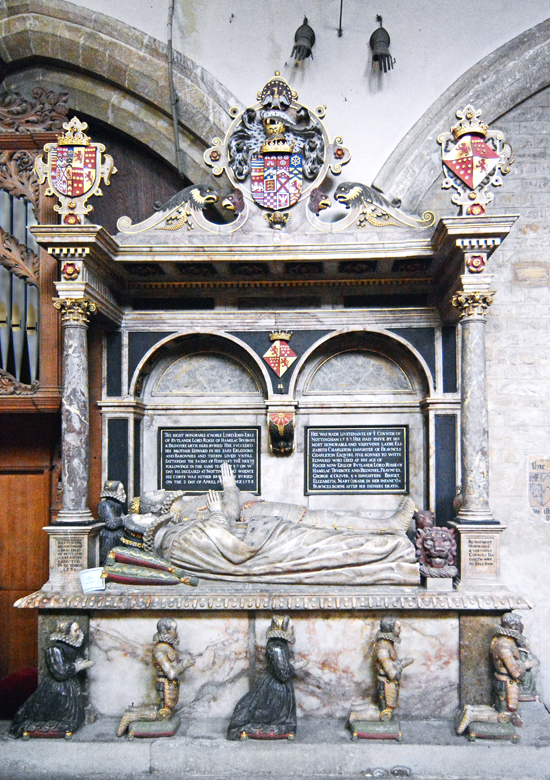

Above: Thomas Manners, 1st Earl of Rutland (1543) & 12th Baron de Ross of Helmsley and his second wife, Eleanor (Paston) (1551). Alabaster with two recumbent effigies on tomb chest with weepers. Inscription. Gothic with early Renaissance detail. By Richard Parker of Burton-onTrent; it cost £20 Right: Henry Manners, 2nd Earl of Rutland (1563) & 13th Baron de Ross of Helmsley and his first wife, Margaret Neville (1559). He married a second time after her death. Continued on the far right → |

|

Above: Alabaster table tomb, under which the effigies and on top three smaller kneeling effigies, facing the foot, between which an upright slab with arms; these presumably represent their two sons, the 3rd and 4th Earls and their (?) daughter. Note that he holds a closed book and his feet rest on a unicorn while hers rest on a lion.. |

Above (detail) and right: Edward, 3rd Earl of Rutland (1587) & 14th Baron of Ross and his wife, Isabel (Holcroft). Alabaster. Note the small kneeling figure at the foor of the monument. This - and the monument to the 4th Earl - were by Gerard Johnson in Southwark and shipped north, costing £100 each. They had one daughter but no sons. The former - Elizabeth Manners - is shown kneeling at the foot of the monument and became 15th Baroness de Ross but the earldom passed to his brother. Note right: the medieval effigy of a lady on the floor and the foot of the monument: information about this is given above but there are no other photographs. Below left: John Manners, 4th Earl of Rutland (1588) and his wife Elizabeth (Charlton) He was the brother of the 3rd Earl, who died without male issue, and had ten children who either kneel at the head and foot or on the floor at the side of the monument. Alabaster. Below centre: Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland (1612) and his wife, Elizabeth (Sydney) (1612) He was son of the 4th Earl. He was involved in the Essex Rebellion of 1601, for which he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and heavily fined. He had no children and it is speculated that the marriage was not consumated, possibly because he suffered from syphilis. Alabaster; between columns at the side, figures of Labour & Rest. By Nicholas Johnson and costing £150. Below right: Franics Manners, 6th Earl of Rutland (1632) and his first wife, Frances (Knyvet) and second wife Cecily (Tufton)Alabaster Effigies of the Earl and his two wives at different levels. He succeeded to the title following the death of his brother, the 5th Earl who died without issue. The two kneeling figures to the east and one to the west, represent his daughter, Kathryn, by his first wife and his two sons Henry (1613) and Francis (1620) by his second. As he died without male issue, the title passed to his younger brother, George.The inscription refers to his two sons being "killed by wicked practice and sorcery." This refers to three women: The Witches of Belvoir. Note: to the left of the monument is the alabaster monument with effigy to John, Lord Ross (1421), which is similar ot that of William, Lord Ross (1414), shown above. Above this can partly be seen another wall monument. To the right is the monument to George, the 7th Earl. See above. |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Left: John Manners, 8th Earl of Rutland (1679) and his wife Frances (Montagu). He inherited the title from George, the 7th Earl, who had died without issue. He was great grandson of the 1st Earl. He was a moderate Parliamentarian who took the Covenant. He had seven children. Marble by Grinling Gibbons: two standing figures in Roman dress with urn between them. Note the partying putti above! Above in foreground from left to right: 1. The First Earl. 2. The Second Earl. To the side of 1. is a floor brass; this is almost certainly that to Henry de Codynton, Rector (1404), mentioned in 'Other Monuments' above. In the background: 1. The Sixth Earl. 2. The Seventh Earl. 3. The Third Earl. There is another wall monument between 2 and 3. There may be the effigy of the lady below the window next to this |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

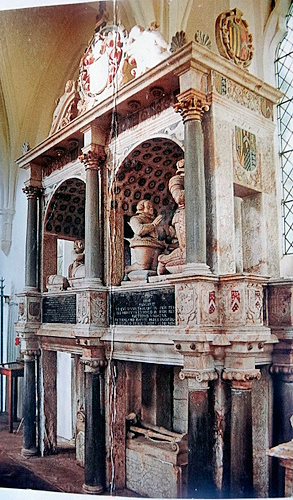

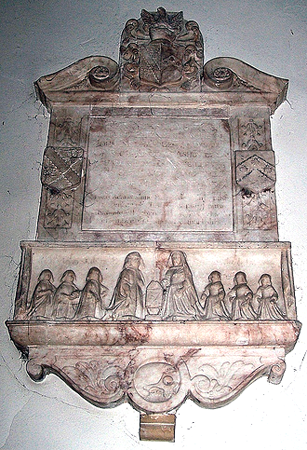

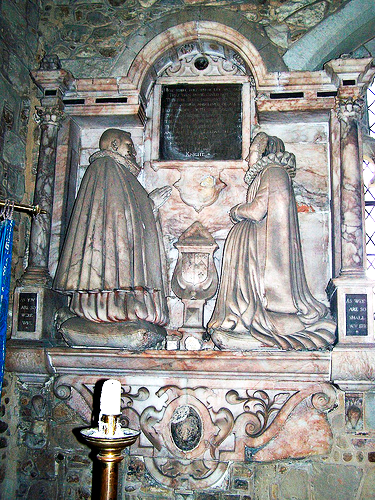

| Left and above:

George Shirley (1622) & Frances (Berkeley) (1598)

and their children. Frances died in childbirth. Their children were: George (died in infancy), Henry (1634), Thomas (1654), John (died in infancy) and Mary Father George and sons Henry and Thomas kneel in the right compartment, while Mother Frances kneels with daughter Mary in the left; two cradles with babies George and John are placed beside them. Below Father George lies a skeleton on the lower level. Alabaster. |

||||

|

|

| Left: Francis (1571) & Dorothy (Giffard)

Alabaster; sons and daughters hold the shields Above: John Shirley (1570) son of Francis & Dorothy. Alabaster by Gabriel Royley of Burton on Trent. Contract survives. |

| Edmondthorpe - St Michael |

| In the care of the Churches Conservation Trust |

|

|

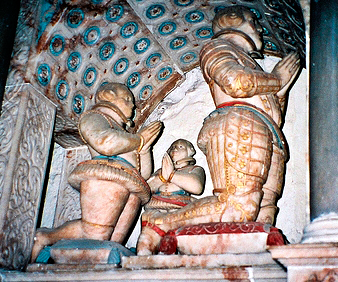

| Sir Roger Smith (1655), two wives, Jane (Heron) (1599) and Anne (Goodman) (1652); also his son, Edward (1632) at 34 & his grandson, Roger (1646) at 19. Both son and grandson predeceased Sir Rogrt.. Alabaster. | Edward Smith LLD (1769) Descended from Sir Roger Smith Alias Heriz by his second wife. See left and below. |

|

|

A Local Legend |

|

Note the red stain in the alabaster on the

wrist below the bracelets and the proximal part of the hand of

Lady Anne, the lower of the two wives in the photograph above,

which is also reproduced on the left. This gave rise to the legend that Lady Anne was a witch who could transform into a cat. When a cat she was attacked by her butler with a cleaver, injuring her paw. The cat dissappeared but when Lady Anne returned her wrist was bandaged and she bore a red scar all her life on her wrist. |

|

|

|

|

|

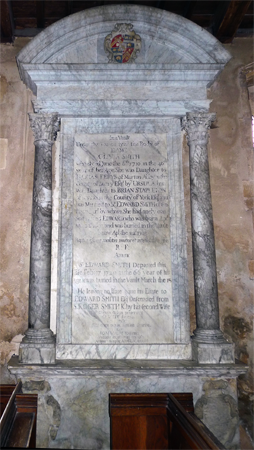

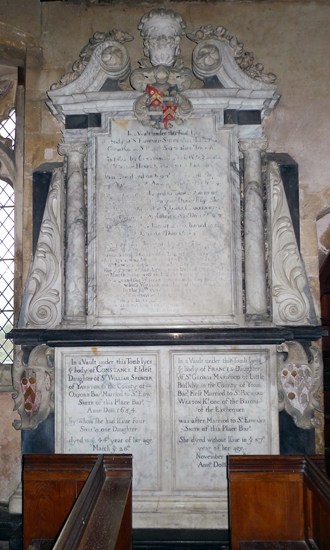

| Dame Olivia Smith (Pepys) (1710). Also her husband, Sir Edward Smith (1720). They had one son who died in 1703 so on the death of Sir Edward the estate passed to Edward Smith, descendent of Sir Roger Smith by his second wife. (see above) | Edward Smith (1762) On the panels below are obituaries of his two wives: Constance (Spencer) and Frances (Marwood) The dates are obscured by the pews. The information on this monuments is difficult to read owing to faded paint work |

Peter Boundy MA (1710), Rector.

An attempt to make a double 13th century sedilia into a monument to the Rector & his wife during the lifetime of both; thedates of death have not been completed. Inscription in English, Latin, Greek and Hebrew. |

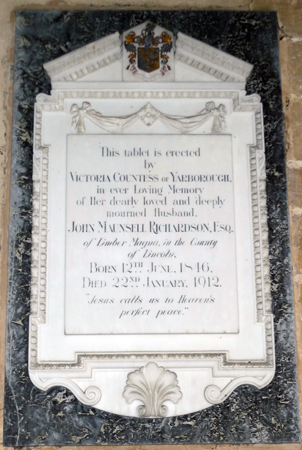

Victoria Richardson, Countess of Yarborough (1912) | Margaret Smith (Horsman)

(1780) Relict of Edward Smith LL D, whose monument is shown above |

| Also: William Ann Pochin (1901) White tablet on black backgrouns; pediment with frieze with row of pelicans. |

| Smith or Heriz |

| It appears that the name change came about as follows. The original name was Heriz but in the time of Henry VII, one William Heriz assumed the name and arms of Smith, in consideration of the manor of Withcock that he had inherited. However he still bore the arms of Heriz in the second quarter of his armourial bearings. |

| Fenny Drayton - St Michael |

| Nicholas Purefoy (1545) &

Jane.

Incised slab on tomb chest with Early Renaissance

decoration and weepers. George Purefoy (1593) & Edward (1594), erected in 1596. Two big arches on attached columns. George Purefoy (1628) & two of his three wives Six poster with recumbent effigy on tomb chest which is surrounded by kneeling children. Above the recumbent effigy are the kneeling figure of Mary (Knightley), George's first wife, and of Jane (Roberts), his third wife, who erected the monument. His second wife, Dorothy, is not represented, possibly because she had no choldren. |

| Illston-on-the-Hill - St Michael and All Angles |

|

|

|

|

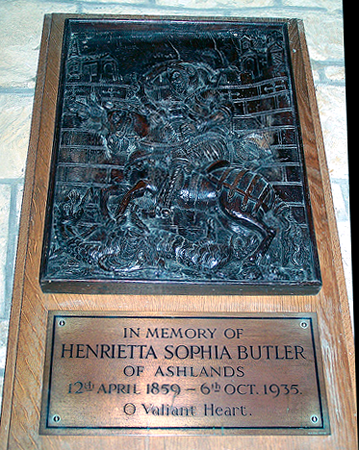

| Left:

'Neare this place

lyes interd Elizabeth

wife of John

Nedham Gent and daughter of Richard Kinge of Ashby de

la Laund in Lincs Esq. She left 3 sons & 3 daughters and dyed ye

26 Febr Ano Do'i 1639.

Twas' Adams Sinne that laide me in the dust By virtue of Christ risen, rise I must: That blessed morne whilst I expecting lye. Above: Henrietta Sophia Butler (1935) |

Two halves of an incised slab which have not been photographically joined. Edward Needham (1617) and Wife as shrouded skeletons. Mentioned in Greenhill, where it is reported partly covered | ||

|

|

| Leicester: Cathedral - Cathedral Church of St Martin |

| Leicester Cathedral is a Cathedral of the Modern Foundation, the see being founded in 1927; before that St Martin's was a parish church |

Two civilians, incised slab of Tournai marble, once inlaid. Ancaster stone slab (15th century), four times reused. John Whatton (1656) & two Wives, busts in niches by Joshua Marshall. George Newton (1746), three free standing busts on big pedestal. John Johnson (1814), architect, Rococo standing figure of Hope with anchor, designed by the commemorated and carved by J Bacon. Rev E T Vaughan (1829), standing figure, Grecian. King Richard III (k. 1485), slab erected in 1980, by David Kindersley. The King was buried in Greyfriar's Church in the city following his death at the Battle of Bosworth. Both tomb and church were destroyed at the Dissolution when his remains also dissappeared. This is a just a memorial slab although it may, to the casual observer at least, resemble an slab over a burial vault; it is not. Following the discovery of King Richard's remains they were eventually reburied in Leicester Cathedral. This and the form that the monument takes are discussed below. |

I have been visiting churches since the mid nineteen-sixties and I am sorry to say that Leicester Cathedral, when I visited in 1967, was the most unfriendly and discourteous church I have been to. I expect that this unfortunate attitude has changed in more recent times with changes of leadership and now that they have a 'tourist attraction' I am certain that it will have done so. |

The Second Burial of King Richard III A Not Uncontroversial Issue |

| King Richard III, the last Plantagenet king of England, was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 and his body put on display in nearby Leicester for three days (see note 3 below) before being unceremoniously buried in the Greyfriars' Church in that city. An inexpensive monument was ordered by the victor of Bosworth, Henry VII, some ten years later, possibly either in order to pacify any Plantagenet sympathizers, or, some say, as some form of reconciliation; I think we can dismiss this latter as Henry VII and his son, Henry VIII, both had a habit of permanently ridding themselves of any possible Plantagenet claimants to the throne. Greyfriars' Church and Richard's tomb were destroyed at the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The tomb was said to be of 'variegated' alabaster with a 'likeness' of the late King but there is no reliable information regarding the design it actually took: it may have been a table tomb or incised slab with an image of the Richard. A copy of the Latin epitaph, which may have been written on a metal plate, has survived. The site of the friary was bought by the mayor of Leicester - Robert Herrick - who converted part of the site - the choir where Richard had been buried - into a garden where he constructed a stone pillar as a grave marker of the king, so the site of the grave must have been known then. This pillar was visible in 1612 but lost by 1844. There was no reliable record of what actually happened to Richard's remains although there were rumours that his body was ejected from his grave and thrown into the River Soar. This rumour was begun by antiquarian and map maker John Speed and, although there was no reliable source for this claim, it was widely believed ⁻¹ and indeed a plaque was installed on Bow Bridge, spanning the Soar, in 1856 at the site where Richard's body was said to have been thrown into the river.. In 2009 screen writer Philippa Langley, then secretary and now president of the Scottish branch of the Richard III Society, who had carried out extensive local research into Richard's grave site, became convinced of its location. Ms Langley, an organizer extraordinaire, was determined to find Richard's body and managed to convinced the head of The University of Leicester Archaeological Services of the validity of her project as well as persuading a number of groups to provide the necessary funding. Together with historians and other interested parties she formed the Looking for Richard Project. The group initiated plans for excavation of the site which was to be overseen by The University of Leicester Archeological Services. One of the backers had to drop out before the project began and the whole thing was almost cancelled but, ever resourceful, Ms Langley organized a world wide fund raising project by the Richard III Society to eliminate this shortfall. The excavation began on August 24th 2012. The John Speed rumour was shown to be false when a skeleton, thought to be that of Richard, was excavated in September 2012 at the site of Greyfriars' Church which is now a car park. There was no coffin or any other artifacts and it appeared that the body had been hastily and clumsily buried in a grave that had been dug too small, so that his body had been forced into position. The skeleton was in remarkably good condition with only the feet and left fibula missing, which was probably from damage by later excavations for foundations, as well as some finger bones and teeth. It showed many injuries consistent with death in battle and showed that the deceased had suffered from scoliosis ⁻ ² - a curvature of the spine. All of this suggested that there was a very good chance that this was indeed the body of of Richard. Detailed examination of the remains - including matching the mitochondrial DNA with two matrilineal descendents (of Richard's sister Ann) of the 17th and 19th generations, showed that the body was, beyond reasonable doubt, indeed that of Richard. This was announced on February 4th 2013. Incidentally, the archaeologists did not discover the alabaster tomb slab - or even the slightest fragment - in their excavations which suggests that it may have been removed intact and possibly reversed so it could be used as a paving slab or similar. This has been found to occur from time to time: there is even an example in Mersham in Surrey of an whole effigeal slab having been subject to this, with the builder even taking the time and trouble to chisel away a good portion of the effigy itself so it could be more successfully used as a paving slab. The Ministry of Justice announced in February 2013 that the University of Leicester had the authority to determine where King Richard should be buried. This would necessarily be subject to the Ministry's reasonable requirement that a license for the excavation of human remains is issued subject to such remains subsequently being buried in consecrated ground as near as possible to the site of excavation. The University of Leicester confirmed that its intention had always been to bury King Richard in Leicester Cathedral. Leicester Cathedral as Richard's burial place did not receive full public support and other possible sites were suggested, as listed below; after all as Leicester Cathedral was not a cathedral at all in Richard's time but a parish church, it could be said that it was not fit for a king. In fact Leicester parish church did not become a cathedral until 1927 under circumstances (industrialization and population growth) that Richard could never have envisaged. 1) Reburial in the Car Park. This is not as callous as it sounds since it fulfills the Ministry of Justice's requirement of reburial in the nearest consecrated ground: the modern car park was built over the church of a friary so, unless consecration has an expiry date, the ground would certainly be consecrated. I presume that this suggestion was to include burial in a substantial coffin placed in a lined vault and that a fitting monument would be placed over the grave, protected by railings. 2) Westminster Abbey. A number of English and British monarchs and their consorts are buried in Westminster Abbey but many are not, although Richard's wife (Anne Neville) is interred there but without a contemporary monument. If Westminster Abbey had been chosen most of us would not have been able to afford to visit the grave all that often! 3) York Minster. It has been said that this was Richard's choice of burial place although there are no records of this or indeed of his choice of anywhere else. Richard spent his early years in Yorkshire and was even governor of the North under his brother Edward IV. It is said he was liked and respected in Yorkshire and especially York. Richard also founded a chantry chapel in York Minster. 4) Arundel Cathedral is a Roman Catholic cathedral and was another suggestion as Richard had been a Roman Catholic. We might say he had little choice, as being a Protestant was not an option and therefore he was in effect, a member of what was in his time the church in England. Arundel Cathedral was not only not a Cathedral in Richard's time, it did not even exist, having been built in the nineteenth century. 5) Worksop Priory. This was suggested by the Member of Parliament for Worksop apparently as a compromise: Worksop, in Nottinghamshire, is half way between Leicester and York. It would also give Worksop a needed lift. 5) Fotheringay in Northamptonshire is where Edward, 2nd Duke of York was buried after his death at the Battle of Agincourt. His grandson Richard, 3rd Duke of York and his son Edmund, Earl of Rutland , who were killed or executed after the Battle of Wakefield, and who were originally buried at Pontefract, were also subsequently buried there, as was the 3rd Duke's wife, Cecily (Neville), the 'Rose of Raby'. So Fotheringay church was becoming a Yorkist mausoleum and therefore this is a valid suggestion. Richard had also been born in Fotheringay. ⁻ ³ Other suggestions were St George's Chapel, Windsor, which appeared to have been planned as a royal mausoleum by Richard's brother Edward IV and was eventually to become one, although hardly a Plantagenet, let alone a Yorkist, one. Others, way down the list, are two places where Richard had founded collegiate churches: Middleham, Yorkshire and Barnard Castle chapel, County Durham. It may be interesting to record the comment that the one place Richard may not have wished to be buried was Leicester which contained the Lancastrian mausoleum! ⁻ ⁴ However this was probably said with tongue in cheek as theYorkist kings still continued to provide patronage to this church even with these Lancastrains tombs. It appears that only two of these suggestions received any significant public support with Leicester receiving 3,100 more votes that York. The Richard III Society appeared to sit firmly on the fence, rather like the Earl of Northumberland at the Battle of Bosworth. All other options were firmly rejected in Leicester with The Mayor of Leicester being quoted as saying: 'The bones leave Leicester over my dead body'. However a legal challenge did come from a group calling itself The Plantagenet Alliance ⁻ ⁵, a group founded shortly after the body was confirmed to be that of Richard and which consisted of up to forty of Richard's collateral descendents ⁻ ⁶ and others, who wished the King's body to be buried in York Minister, which was already the second option. They applied for a judicial review which, surprisingly to many, was granted by Mr Justice Haddon-Cave on the grounds that the original burial plans had ignored common law. The review opened on 13th March 2013 and the three judges of the High Court gave their decision on 23rd May that there were 'no public law grounds for the court to interfere'. This action had left the burial place uncertain for nearly a year. The Dean of Leicester had been quoted as saying that this action was 'disrespectful' and that the Cathedral would not invest any more money in Richard's burial plans until this was finally decided; it had already invested one million pounds in refitting the Cathedral. One source is quoted as saying that York already has several tourists' attractions, it is only reasonable that Leicester should also have one, quite ignoring or forgetting the basic fact that this is the burial of Christian English king that is being considered, not a branch of Disneyworld. So the Plantagenet Alliance lost their case for Richard's second burial in York Minster. Leicester City Council spent £850,000 on purchasing land opposite the cathedral, including the now famous car park. They were then to spend £4.5 million pounds on building a Richard III visitors' centre on this land which would show the original grave under a suitable cover. They estimated this would attract 100, 000 visitors per year. The Cathedral spent £1.3 million on the King's new tomb More controversies were to follow. Richard's bones when discovered were found to still be in a more or less correct anatomical relationship. However the Cathedral planned to place the bones in an lead ossuary with no attempt at articulation; many found this disrespectful as the King would not be buried in the usual manner. The ossuary was then to be placed in a wooden coffin, so giving the illusion at the funeral that a body was being buried. The Dean was reported as being quite unrepentant about the ossuary. The tomb design then caused further controversy. Leicester Cathedral had announced a competition for the design of the King's tomb after their own favoured design of a simple ledger was rejected following strong local opposition. There was already such a stone, by David Kindersley, in place since 1980: this stone certainly gives the illusion that it covers a burial site although, in all fairness, it was written on this stone that Richard was buried in Greyfriars' Church. This stone, now rather pointless, was to be discarded. A new design was unveiled in September 2013 which consisted of a deeply incised cross on a large stone block which itself stood on the floor which would be inlaid with a white rose design. This did not meet the approval of the Richard III Society who felt that this monument was quite unfit for a medieval monarch and warrior and withdrew the pledge of £40,000 they had originally offered towards the cost of the monument. The Cathedral authorities retorted that they would not be held hostage by the Richard III Society and that they had never banked on that money anyway. The Church Monuments Society did not express an opinion. The Richard III Society had designed a tomb (this is illustrated at the end of this article) which was a relatively simple limestone sarcophagus, in a medieval style certainly but not a slavish copy of a medieval tomb, with two brasses inlaid on the lid, one of Richard's arms and the other his details. I presume this would have involved the burial of Richard's remains in a coffin actually inside this sarcophagus. A second design was unveiled is year later in June 2014. This was the final design, although similar in may ways to that of the previous year but the vault in which Richard was to be buried would be closed with a dark stone plinth with the King's name, dates, arms and motto marked inscribed on it. Over the plinth was a two tonne block of Swaledale fossil limestone (so Yorkshire had to come to Richard, rather than Richard to Yorkshire) with a very deeply incised cross. Philippa Langley probably expressed the feelings of the Richard III Society about the design, criticizing the deep slashes of the cross, the black plinth and the lack of a white rose, all of which held an important significance to her and certainly to many others. The Dean had said that the design 'reflects the era in which it was designed' and that 'anything else would be a pastiche of a mediaeval tomb.' He cited the tomb of Reginald, Lord Cohham ⁻ ⁷ as something that was not wanted.. Philippa Langley's opinions - remember she was the person who initiated the whole project - were simply dismissed by the Dean., who is also reported as stating that Richard III does not belong to Philippa, nor the Richard III Society, he belongs to the whole nation. After Ms Langley reported that the people she had interviewed in Leicester, about eighty percent, did not favour the design (and I have no reason the dispute this), the Dean retorted that he had found exactly the opposite, which I suppose could have been predicted. Richard's reburial ceremony took place between 22nd and 27th March 2015 and is best described elsewhere; I will just add here that low key is not understood by those who organize such things. He was finally buried on the 26th with the attendance of the chosen few, which did include a limited number of members of the public chosen by ballot, and the tomb was unveiled to the public on the 27th Aftermath. In July 2017 Leicester Cathedral planned to stage a production of Shakespeare's play Richard III. The indomitable Philippa Langley strongly objected to this plan as the play blackens Richard's character to an absurd extent as well as being historically inaccurate. She is quoted as having said that this action was contrary to the Dean's undertaking that the King would be buried with dignity and honour. In my own personal view the play is Tudor propaganda and Richard is portrayed as little more than a pantomime villain. The Dean ignored Ms Langley's objection and the play was staged as planned; both performances were sold out. So now we know what it was all about: but then it always is. NOTES ⁻ ¹ This was certainly the current opinion when I first visited Leicester in the late 1960's. It is thought that this tale became confused with that of the fate of the body of the church reformer and Bible translator, John Wycliffe (c. 1320-1384), whose body was exhumed from his grave in Lutterworth church, also in Leicestershire, burned and the ashes thrown into the river. Another similar fate was said to have occurred to the bodies of King Stephen and his family who, with his wife Matilda and possibly their son Eustace, were buried in his foundation of Faversham Abbey in Kent. The Abbey, of which little now remains above the ground, was excavated in 1965 and two large pits - almost certainly the royal burial vaults - were discovered at the eastern end of the choir; these were empty, there being no signs of the coffins or other remains. The Abbey had been surrendered in 1538 and the burial vaults clearly robbed soon afterwards. Thomas Southouse, writing about 130 years after the events stated that the tombs were robbed for the lead of the coffins and the bodies thrown into the nearby river. However, there is a local tradition that the royal remains were reburied in a tomb in the nearby church of St Mary of Charity, which may be seen today. The brass on this tomb is Victorian. The excavations were not able to determine which of these tales was true. ⁻ ² The condition was diagnosed as adolescent onset scoliosis. As the names suggests this is not present at birth or during childhood but rather develops later, often becoming more severe over time and leading to increasing disability. In Richard's particular case, it caused one shoulder to be higher than the other but he was certainly not the rather silly deformed monster of Shakespeare's play and of popular myth. Richard led an active life style and was a skillful warrior. ⁻ ³ The First Duke of York, Edmund of Langley, was the son of King Edward III and father of the aforementioned Second Duke. He was born at the Priory of King's Langley, in Hertfordshire and buried in the priory church on his death. He tomb was moved from the priory church at the Dissolution to All Saint's Church in the town, where it may still be seen. ⁻ ⁴ The Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady of the Newarke in order to distinguish it from the older Church of St Mary de Castro, both collegiate foundations, was founded by Henry of Grosmont, first Duke of Lancaster in 1353 and contained his tomb as well as those of his father, Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster; Constance of Castile, second wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster; and Mary de Bohum, first wife of King Henry IV, the first Lancastrian king. These monuments are lost but the alabaster monument of Mary Hervey (c. 1408), a member of the household of John of Gaunt was moved to the nearby chapel of Trinity Hospital. Newarke means 'new work' and refers to a medieval development outside the original city walls. The church was part of this development. ⁻ ⁵ The Plantagenet Alliance has been much criticized and derided. However, it must be said that whatever their motives were in wishing that King Richard be buried at York, which they honestly believed to be right and proper, they were certainly not driven by one eye on any potential financial gain. ⁻ ⁶ This means not via Richard's children. Mitrochondrial DNA is not passed on through the male line. Richard had one child with his wife Anne (Neville), Edward of Middleham who died aged ten and presumably had no children plus two illegitimate children, John of Gloucester and Katherine but nothing is known of their decendents or even if they ever truly existed. ⁻ ⁷ This is a rather curious remark to make. Reginald, Lord Cobham, who died in 1361 and fought in the Hundred Years' War under Edward III and the Black Prince, was buried in St Peter and St Paul's church in Lingfield, Surrey, the earliest parts of which date from the 14th century. The church was in medieval times a collegiate church and contains the tomb and effigy of Lord Cobham which may be seen today. Leicester Cathedral, although a cathedral of the modern foundation, is itself a medieval church, although very much restored. Why Lord Cobham's monument was singled out when referring to a 'medieval pastiche' is difficult to understand; the design from the Richard III Society would have been much more in keeping for a medieval man and a medieval church yet with a modern slant and certainly far more in keeping than that which was selected. A PERSONAL NOTE As I have implied criticism about the burial site, tomb design and other aspects of this unfortunate saga I feel it would be fitting only to include photographs that I have taken myself, but I have none. Relevant photographs, especially those of the several tomb designs, can be found on the internet as can much information about the whole sorry saga. I have used many sources, a few of which are either sometimes contradictory, incorrect or vague, in compiling the above article. They are all from secondary sources so I would very much welcome any access to primary sources, hearing from any of those who took part in this tale eapecially members of the Richard III Society, or just my errors pointing out. The best book on the excavations and examination of Richard's remains is Richard III, The King under the Car Park by Mathew Morris and Richard Buckley (University of Leicester, 2013). This was written by two of the archaeologists who led the dig and the book contains many excellent photographs and other illustrations as well as much relevant and interesting information. Another good book which also deals with the background story is by Philippa Langley herself with historian Michael Jones; this is The Search for Richard III: The King's Grave (John Murray, 2013) |

|

|

| The King Richard III Society

Design for Richard's Monument These photographs are copyright and used by kind permission of The Richard III Society To whom grateful thanks |

|

|

|

| Peatling Magna - All Saints |

Above and near right: William Jervis (1614) with wives Ann & Frances |

Right: William Jervis (1618) and Elizabeth (Shepperd) Arms on the desk are those of Jervis impaling Shepperd. He married twice more. Below: Willaim Jervis (1597) with Katherine He died aged 94. There are 25 children around the tomb chests and 8 swaddled infants; they surround William of the above |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Skeffington - St Thomas a Becket |

|

|

|

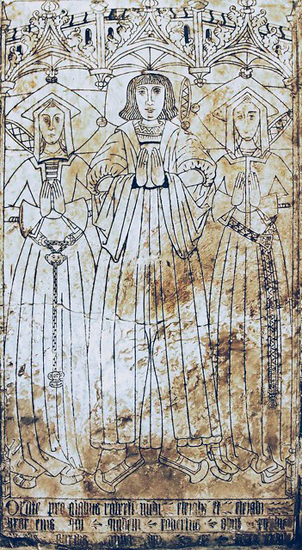

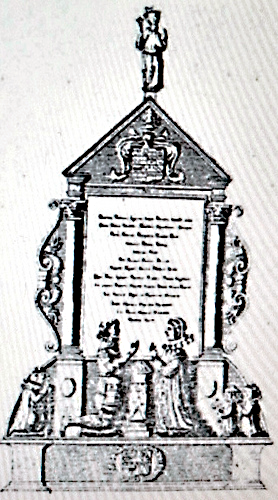

Drawing of the original Thomas & Isabella Skeffington monument. |

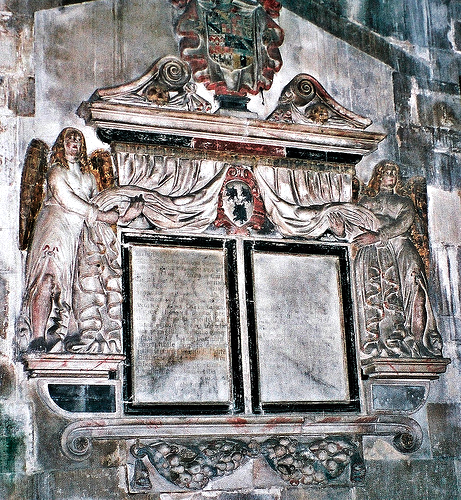

| Above: Thomas Skeffington (1600)

& Isabella (Byron) (remains). A

drawing of the original complete monument is shown on the far

right. Right: Sir John Skeffington, 2nd Bt (1651) Centre right: Drawing of incised slab to Thomas Skeffington (1543) & Margaret (Stanhope) (1539) Now only the bottom of the slab is discernible |

| South Kilworth - St Nicholas |

|

|

| Effigy of a priest |

| Stapleford - St Mary Magdalen |

|

|

| Geoffrey Sherard (1492) and Joyce brass with fourteen small standing figures of children. |

|

|

|

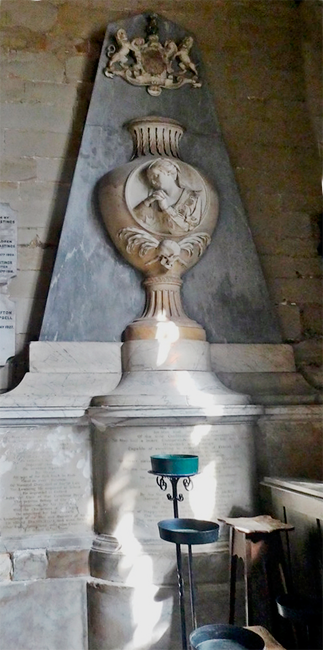

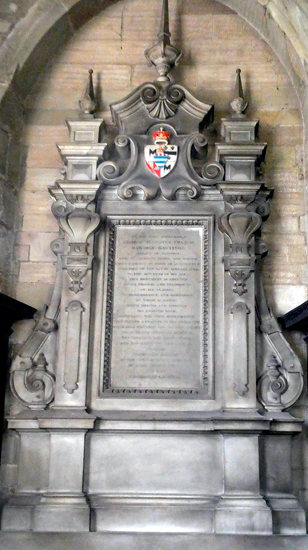

| Bennet Sherard, 1st Earl of Harborough (1732),. Grey marble obelisk with busts and arms behind. Signed M. Rysbrack. Fecit | ||

|

|

1st Lord William Sherard of Leitrim (1640) & Lady Abigail (Cave). Black & white marble. The tomb chest has black columns at the corner holding the black covering slab. Eight children kneel at borders of the slab and there are three recumbent infants. Three are shown in detail to the left, right and above. |

|

|

|

|

|

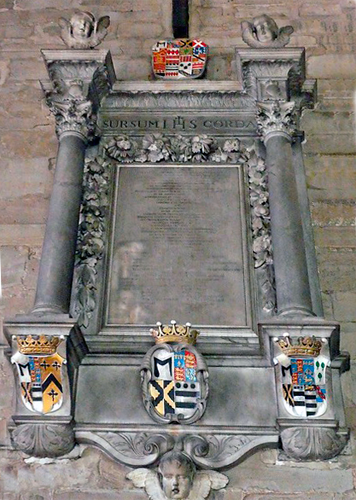

| Four

busts arranged together: At the top: Bennet Sherard,

Baron Sherard of Leitrim (1699),

son of William Sherard and Abigail Cave (above) and father of

Philip Sherard, 2nd Earl of Harborough (1750),

who was buried at Whissendine, (central bust above),

and grandfather Bennet Sharard, 3rd Earl of Harborough

(1770) (right bust above) and to

Robert Sherard, 4th Earl of Harborough (1799).

(left bust above). The monument to the Firat Earl is show separately above; he was succeeded by his second cousin Philip as the Second Earl (above) On the base of the monument is a black plaque, with the following inscription: 'Here lyeth ye bodies of Francis Sherard Eſq who was ye sonne & heire of George Sherard Eſq, who departed this life ye 13th day of December in ye yeare 1594 aged 65 yeares & Anne his Wife ye eldeſt daughter of Gregory Moore of Burne in ye Count: of Lincolne Eſqr, by whom he had iſſue 3 Sonnes Philip, William & George & 1 daughter Roſe' The further part of this inscription has not been photographed. |

|||

|

Other Monuments |

| 1. Robert Sherard, 6th and Last Earl

of Harborough (1859) Signed: T Gaffin. Regent's

Street, London (Left) 2. Philip Sherard, 5th Earl of Harborough (1807) and his wife, Eleanor (Monkton) White tablet with pediment on black base. 3. Mary Eliza (Sheranrd) Countess of Harborough (1886) Buried at Exmouth, Devon. She married: 1) Robert, 6th Earl of Harborough. 2) Mjr Thomas William Clagett of the Madras Light Cavalry. White scroll on black peidmented base. |

|

|

|