| BOOKS | ||

Lost for Words (or a Word) |

||

| In English there does

not appear to be a generic word for village, town

and city. In fact, this very question was posted on the

internet and the conclusion was reached that there is no

such a word, although some were suggested such as community, settlement

and a number of others. However, it was generally felt that

these words had other connotations, so none was generally found

to be satisfactory. It was felt furthermore that what might be

found suitable in Britain would not be so in the USA, Australia

and other English speaking countries. I suspect too that a

suitable word in England may not be suitable in Scotland. The RCHM divides Britain into counties, the counties into hundreds (an long obsolete term) and the hundreds into parishes. That last word is probably the most satisfactory for our purpose here. I am aware there are ecclesiastical parishes and civil parishes and their boundaries do not always - as you might expect - correspond. But - as Mr. Holmes would say: 'when you eliminated the totally unsatisfactory, whatever remains, even if not quite ideal, must be the word' |

This list is far from complete as I have neglected a lot of the more recent books although most of the earlier book have been included. I may add these later given the book and the time.

| A Note of Caution |

Many of these books are old - some very much so - and the information in them often needs to be revised in the light of modern research. But we do have to tread carefully here as this subject is not a rigorous scientific one. Many revisions are the result of very careful research and sound reasoning while many are not: sometimes a whole complex theory is built up from the flimsiest and most ambiguous of evidence as well as the most flawed reasoning, often in order to 'get published' as soon as possible. Then there is the 'generation game': I remember at university how we, the young, rejected, often with a smile or sneer, the ideas of the older generation as being old fashioned, unscientific, not evidence based; what we are being taught is new and everything it should be. Now that which I was taught is being regarded in exactly the same manner by the newly arrived generation, who promote their own 'new' ideas, which are often not so new but revised views of those we had rejected! |

every brass,

not just the very fine ones but even those very simple brasses which

often go unnoticed, such as those small rectangles of brass screwed to

the back of chairs. The books are profusely illustrated but the text is

almost in note form, which is all that is really needed. Those who conceived

this series of books and continue to compile them must be congratulated.

every brass,

not just the very fine ones but even those very simple brasses which

often go unnoticed, such as those small rectangles of brass screwed to

the back of chairs. The books are profusely illustrated but the text is

almost in note form, which is all that is really needed. Those who conceived

this series of books and continue to compile them must be congratulated.

I regret to say that there is nothing similar about church monuments; that is to say there are no series of volumes which have been produced as a county series solely about church monuments. There are certainly a number of books about church monuments in general, some beautifully illustrated with photographs, etchings, engravings and lithographs; there are also books about specific monuments such as wooden tombs, alabaster tombs, military monuments, some of these listing as many monuments as could be discovered. There are, in fact, a few single county books but these, with one exception, are not particularly well illustrated; the exception is Chancellor's Essex, a massive and hefty book wonderfully illustrated with lithographs of drawings but you will have to carry it in the boot of a car rather than your pocket! More on this subject later.

There are a number of such books and more are appearing all the time. I will only deal with a handful here. Some are beautifully illustrated while others have no illustrations at all, or very few. I have presented the various books in sections more or less of the same type

monuments was evident in his

earlier work. He made a lengthy survey of the inscriptions on monuments

in the dioceses of Canterbury, Rochester, and Norwich. He did

not, however, make any sketches of the monuments nor did he record

heraldry or genealogy. So from those latter aspects the book is

probably not of great interest; however Weever does record

epitaphs which have since been lost. His book was published in

1631. monuments was evident in his

earlier work. He made a lengthy survey of the inscriptions on monuments

in the dioceses of Canterbury, Rochester, and Norwich. He did

not, however, make any sketches of the monuments nor did he record

heraldry or genealogy. So from those latter aspects the book is

probably not of great interest; however Weever does record

epitaphs which have since been lost. His book was published in

1631.John Weever died the following year, 1632, and was buried in St James, Clerkenwell. A monument was constructed to his memory which was destroyed when the church was demolished in 1788, despite efforts of the Society of Antiquaries whose intervention failed to save it. As mentioned no sketches were made of the monuments at the time of the survey but there are eighteen woodcuts in the book, which were probably supplied by other antiquaries at a later date for publication. |

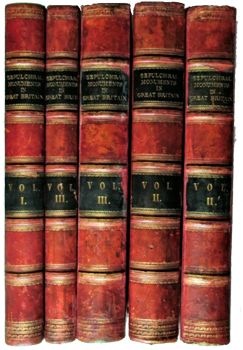

Gough's

Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain. Richard Gough

(1735-1809) was

another English antiquary. His book about church monuments was a

major and thorough study and was formally titled

Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain Applied to lustrate the

History of Families, Manners, Habits and Arts at the Different Gough's

Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain. Richard Gough

(1735-1809) was

another English antiquary. His book about church monuments was a

major and thorough study and was formally titled

Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain Applied to lustrate the

History of Families, Manners, Habits and Arts at the Different Periods from the Norman Conquest to the Seventieth Century.

Periods from the Norman Conquest to the Seventieth Century.

Volume I was in two parts and dealt with the first four centuries, part I being published in 1786 and part 2 in 1796. Volume II consisted of three parts and dealt with the fifteenth century; they all were published in 1796. This work is a fine and detailed example of historical and topographical research and contains many illustrations engravings. However Gough was not an artist so employed a number of artists to execute the initial drawings and the final engravings. Many of these are inaccurate and many rather coarsely produced. The work never did reach the seventeenth century, ending at the fifteenth. These books are big, measuring 1' 2" X 1' 8", and heavy. |

|

Fred H Crossley, FSA.

English Church Monuments A.D. 1150-1550.

(Published by B T Batsford, London. 1921) The secondary title of this book is An Introduction to the Study of Tombs and Effigies of the Medieval Period. We - or the books now come - to a period of the twentieth century when photography had been around for a century but had become more practical when George Eastman invented the 'safety' roll film.† So it is not surprising that photography would replace drawings reproduced by photo-lithography as the latter had replaced etching as a means of the reproduction of images of church monuments. This book deals with roughly the same period as Charles Boutell's book and is divided into three main chapters which, after a detailed general introduction, deal with The Architectural Decoration of Tombs and Chantry Chapel and Effigies, and Costumes. Each chapter is then subdivided into a number of sections dealing with such subjects as the change of style over the years of the monuments as well as of dress and armour, heraldry, the materials used in the construction of monuments, contracts for monuments, associated metalwork, and brasses. There is useful glossary of terms but this is unfortunately combined with the index, a feature which never really works all that well. The book is illustrated with a large number of excellent photographs taken by Mr. Crossley himself and which he rightly considers more important than increasing the amount of text at the expense of illustrations. Frederick Herbert Crossley (1868-1955) was a Yorkshireman but travelled early to Cheshire to become an apprentice farmer. He later studied at Manchester School of Art and became an instructor in drawing, wood carving and design in Cheshire. Church architecture became his great interest and he would travel the country making sketches and taking photographs of his subject. He accepted commissions for designing and actually carving church wood work. He served on a number of committees which were concerned with the repair, restoration and preservation of churches. He wrote a number of books for the publisher Batsford which specialized in books about topography, architecture and other non-fiction subjects. As well as the above, his titles included English Church Woodwork, The English Abbey and Timber Framed Buildings. † The first roll film was introduced in 1885 on a paper backing. In 1889 this was replaced by a plastic one, the highly flammable nitrocellulose. The later 'safety' film simply meant that the backing plastic no longer had this dangerous property. |

Brian

Kemp PhD, D Litt, FSA English Church Monuments

(Published by B. T. Batsford Ltd, London, 1980) This is certainly the best introduction to the subject of church monuments. Professor Kemp writes - and also lectures - in a clear, conscise and logical style with none of the waffle too often associated with this subject. As the title suggests he deals with all church monuments from the earliest Christian times to the nineteenth century. There are 216 pages with 176 illustrations. The book is divided into several chapters dealing with, after an Introduction, each of the following: 1) The Middle Ages, 2) Renaissance of the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries 3) The Seventeenth Century and the Rise of the Baroque. 4) The Nineteenth Century. There is then a chapter on Symbolism and Allegory and section on Further Reading. There are three indices, each dealing with a separate aspect of the subject.  Each chapter is divided into a number of subsections: for

example the chapter on the Middle Ages deals separately with

early grave slabs, monumental effigies, tomb chests and similar

related topics.

Each chapter is divided into a number of subsections: for

example the chapter on the Middle Ages deals separately with

early grave slabs, monumental effigies, tomb chests and similar

related topics.The dust cover has a brightly coloured photograph but all of the other photographs are black and white and skillfully taken. They were produced by the University of Reading Department of History. This subject needs illustrations and books without any or with few, are certainly (as Alice might say) of at least limited use; Professor Kemp does not disappoint. Professor Brian Richard Kemp Ph D, D Litt, FSA (1940-2019) was Professor of History at the University of Reading. He was a long time member of the Church Monuments Society and former President. He was a most helpful person, always willing to answer questions, give advice and discuss many matters. He was also a keen natural historian and musician. |

Brian

Kemp PhD, D Litt, FSA Church Monuments

(Shire Publications Ltd. No. 149 First published 1985, reprinted 1997 and

2010) Softback. This is the younger

sibling of Brian Kemp's other book on

church monuments Following an introduction there are chapters on Historical Development, Effigies, Symbolism and the Making of Monuments. There is then a useful section on places to visit to see a good selection of monuments and a short bibliography. The cover of the latest reprint has a colour photograph but all those inside are in black and white, a few taken by the author himself; still, my copy cost less than £5 a few years ago.

|

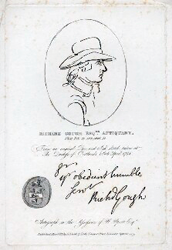

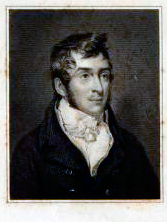

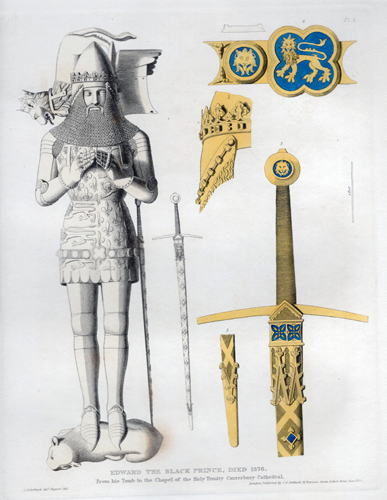

Charles Alfred Stothard FSA The Monumental Effigies of Great Britain. (For the author, by John Murray 1817 - 1832) The twelve original planned parts were eventually bound together in book form. This is a large book about the size of Gough mentioned above.  C. A.Stothard (1786 - 1821) was a historical draftsman, son of the

painter Thomas Stothard. He planned a twelve part work on (as

the title states) the monumental effigies of Great Britain

from the Norman Conquest until the time of Henry VIII,

although this included some in France also. The work includes

very fine etching of the effigies, sometimes with several aspects

of the effigy itself and

details, such as swords, belts etc as may C. A.Stothard (1786 - 1821) was a historical draftsman, son of the

painter Thomas Stothard. He planned a twelve part work on (as

the title states) the monumental effigies of Great Britain

from the Norman Conquest until the time of Henry VIII,

although this included some in France also. The work includes

very fine etching of the effigies, sometimes with several aspects

of the effigy itself and

details, such as swords, belts etc as may be seen in the work on the Black Prince, below. Many are coloured. There is also information

about the individual monuments and a lengthy introduction to the

work. Charles Stothard completed all of the preliminary drawings

for this work in the several churches. He

also completed the etchings for ten of planned parts but the artist met

with a fatal accident in Bere Ferris church in Devon so the

actual etchings for final two parts were carried out by other

artists, including Robert Stothard (Charles's brother), Edward

Blore, Bartholomew Howlett, and C J Smith. The final work was

edited by his wife and the introduction and additional text by

his brother-in-law Alfred John Kemp.

be seen in the work on the Black Prince, below. Many are coloured. There is also information

about the individual monuments and a lengthy introduction to the

work. Charles Stothard completed all of the preliminary drawings

for this work in the several churches. He

also completed the etchings for ten of planned parts but the artist met

with a fatal accident in Bere Ferris church in Devon so the

actual etchings for final two parts were carried out by other

artists, including Robert Stothard (Charles's brother), Edward

Blore, Bartholomew Howlett, and C J Smith. The final work was

edited by his wife and the introduction and additional text by

his brother-in-law Alfred John Kemp.A second edition with additions by and edited by John Hewitt was published in 1876. Further information about C. A. Stothard may be found on this page. |

George Hollis &

Thomas Hollis The Monumental Effigies of Great

Britain

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

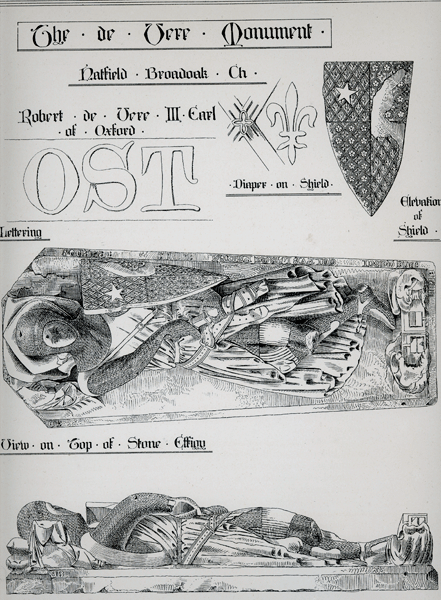

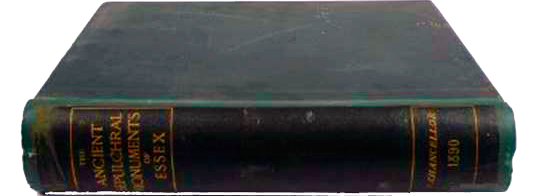

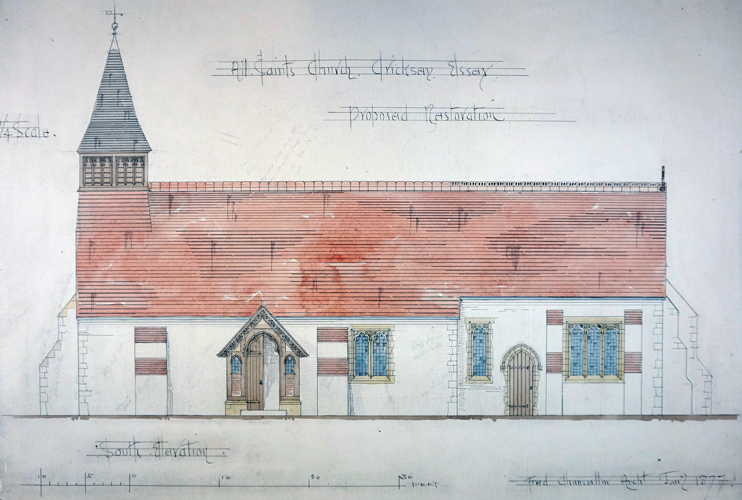

Chancellor's The

Ancient Sepulchral Monuments of Essex (1890)

(Published by Messrs Edmund Durrant Co.

Chelmsford) Frederic Chancellor FRIBA (1825-1918) was an architect, archaeologist, and antiquarian as well as being the first Mayor of Chelmsford, Essex; he later served six further terms in office. His architectural practice was based in that town and he also had a branch office in London . His son, Fredric Wykeham Chancellor BA (1865-1945) later  became a partner in his father's practice. There is a building in Chelmsford designed by Frederic

Chancellor, originally intended as an art school and museum,

which is called the Frederic Chancellor Building in

his honour.

became a partner in his father's practice. There is a building in Chelmsford designed by Frederic

Chancellor, originally intended as an art school and museum,

which is called the Frederic Chancellor Building in

his honour.This book is very large (16" X 12" X 3½" ) and heavy, containing full descriptions of the monuments, their position in the church, the materials of which they were made, any inscriptions, heraldry, family histories, genealogical tables and, most importantly, full page drawings of all of them. None of these were actually carried out by Mr. Chancellor, although he did visit the churches and study the monuments himself, but were executed by a number of artists: John Shewell Corder, Frank Brown, Fred Oliphant, Ernest A Coxhead, Arthur Kent, and F E L Harris. Sometimes J S Corder and F Brown appear to have worked together, although the majority of the work was carried out by John Corder alone. One is signed by F. Wykeham Chancellor, Fred's son and two are unsigned. All of these artists were architects (at one point Fred Oliphant adds ARIBA after his name) so it is not surprising that the drawings have an architectural feel about them, but they are certainly none the worse for that; so we see plans, elevations, renderings of certain details and examples of the lettering as well as the monument's measurements. The printing was carried out by C F Kell, photo-lithographer of London, who may well be the rather obscure subject of the link. Below is a drawing of a church building restoration undertaken Mr. Chancellor's practice and which is signed Fred Chancellor. |

|

|

|

|

|||

Ida M Roper, FLS. Monumental

Effigies of Gloucestershire and Bristol. (Published

by and printed for the Author by Henry Osborne,

Gloucester 1931). Only 100 copies were published,

numbered and signed by the Author. As the title states this book is concerned with

monumental effigies

in the county of Gloucestershire but also the somewhat

mobile city of Bristol. It includes all effigies of

persons who died

As the title states this book is concerned with

monumental effigies

in the county of Gloucestershire but also the somewhat

mobile city of Bristol. It includes all effigies of

persons who died before 1800. It is a small thick

book measuring 6" X 9" X 2¼", so a

bit bigger and much thicker than the original Pevsner

hard backs. The binding appears professionally executed,

but not of the mass produced variety. There are 729

pages and 40 plates, a few containing two actual photographs, in this case black and

white photographs. These were taken by a number of

photographers, mainly

Sidney Pitcher, W. Moline but some

by F H Crossley (see above), R W Dugdale and a few others. The

number photographs would probably not be considered

adequate in a similar book today. before 1800. It is a small thick

book measuring 6" X 9" X 2¼", so a

bit bigger and much thicker than the original Pevsner

hard backs. The binding appears professionally executed,

but not of the mass produced variety. There are 729

pages and 40 plates, a few containing two actual photographs, in this case black and

white photographs. These were taken by a number of

photographers, mainly

Sidney Pitcher, W. Moline but some

by F H Crossley (see above), R W Dugdale and a few others. The

number photographs would probably not be considered

adequate in a similar book today.The author writes in a no nonsense style and the layout is reminiscent of a science text book; we shall see the reason for this later in this short article. The book is divided into rural deanaries,which although the smallest of ecclesiastical geographical divisions (other than a parish, of course) is not particularly helpful to the majority of readers. It is then divided into civil parishes and then churches. Each effigy is described in its own separate section, headed by the name and date, if known, and then there are a number of subsections, namely, (1)Type (knight, lady, judge, abbot etc), (2) Form (recumbent, upright etc), (3) Material, (4) Dimensions, (5) Costume, (6) Supporters to head, (7) Supporters to feet, (8) Description of tomb, canopy and heraldry, (9) Inscription, (10) Remains of painting etc, (11) Condition. (12) Position and former position(s). (13) References. (14) General remarks. (15) Historical notes. There is a good bibliography and index. Ida Mary Roper (1865-1935) was the daughter of a pharmacist and herself a botanist. She was a Fellow of The Linnean Society, the first woman member of the Council of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, and the first woman president of the Bristol Natural History Society. She never married and died in 1935 being buried in the family plot in Arnos Vale Cemetery, Bristol. |

||||

|

Harry A Tummers

Early Secular Effigies in England: The Thirteenth

Century (E. J. Brill Leiden 1980) This is a small hardback rather attractively produced book, 6¼"

X 9½", of 196 pages and 185 plates - that is photographs - of

which there are up to three per page.

This is a small hardback rather attractively produced book, 6¼"

X 9½", of 196 pages and 185 plates - that is photographs - of

which there are up to three per page.Although Dr Tummers is from the Netherlands he writes in beautiful English and has produced a very well researched and detailed book on 13th century secular - that is men, women and children in civilian dress and military effigies ('knights') rather than men (and rarely women) in various ecclesiastical dress. The first 171 pages are written in a rather formal, academic style and consist of several chapters: i)  Preliminary Remarks, ii) The

Tomb, iii) Costume. iv) Attitude, and v) Summary and Conclusions.

In the section on attitude, Dr Tummers discusses in detail the

often misunderstood meaning of crossed legs. Preliminary Remarks, ii) The

Tomb, iii) Costume. iv) Attitude, and v) Summary and Conclusions.

In the section on attitude, Dr Tummers discusses in detail the

often misunderstood meaning of crossed legs.There then follows a useful list of all 213 effigies of the title, divided into three principle sections which he calls, Knightly Effigies, Lady Effigies and Civilian Effigies. This list is divided into several columns: Place name, Length and State, Material, Special Features, Date, and References; this list, so as not to be unwieldy, gives only the most important details. There then follows extensive notes, a bibliography and an index, after which are the many photographs. Last of all is a pull out map which is rather small but helpful when you transfer to a larger scale map. Harry Tummers is a university academic from the Netherlands and a very affable and agreeable man. |

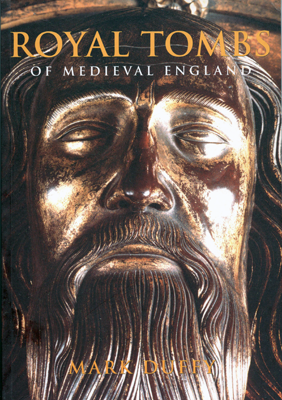

Mark Duffy The Royal Tombs of Medieval England (Tempus 2003) Softback It is curious that two book about similar subject should be published a year apart. However this books only deals  with royal tombs of the medieval period and the layout

is slightly different. By Royal Tombs, is

meant not just monarchs but members of the royal families as

well.

This itself is has a wide definition as we see the Tomb of

the Black Prince (who might have been king) and people like

Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk whose grandson made a bid

for the crown, as of Yorkist decent against HenryVII. Again it is very well

illustrated with photographs, and reproductions of etchings,

engraving, and drawings. A number of the illustrations are in

colour and the reproduction of photographs is generally

better in comparison with Dodson's book. Particular interesting are drawings of tombs that

were planned but never, for various reasons, construction;

the planned effigy of Henry VI, the least martial of kings,

curiously shows him in full armour. Medieval England

means that the book ends in the reign of Henry VII although

it begins with the Norman Conquest. with royal tombs of the medieval period and the layout

is slightly different. By Royal Tombs, is

meant not just monarchs but members of the royal families as

well.

This itself is has a wide definition as we see the Tomb of

the Black Prince (who might have been king) and people like

Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk whose grandson made a bid

for the crown, as of Yorkist decent against HenryVII. Again it is very well

illustrated with photographs, and reproductions of etchings,

engraving, and drawings. A number of the illustrations are in

colour and the reproduction of photographs is generally

better in comparison with Dodson's book. Particular interesting are drawings of tombs that

were planned but never, for various reasons, construction;

the planned effigy of Henry VI, the least martial of kings,

curiously shows him in full armour. Medieval England

means that the book ends in the reign of Henry VII although

it begins with the Norman Conquest.The book is divided into three principle section: 1. 1066-1307 (William I - Henry III), 2.1307-1400 (Edward I ), 3. 1400-1509 (Henry IV-end of reign of Henry VII). Each part is further divided into a varying number of subsections, each slightly different. The longest subsection is that of the tombs themselves but others include burial location, funerary rites, tomb design, and tomb production. |

Mark Downing FSA Military Effigies of England and Wales Nine volumes. (Published by the Author 2010 - )

This is a series of books that I feel we have needed for a long time. It lists, with essential details and photographs, every military monument ('knight') in England and Wales; this includes all the aesthetically unappealing hulks and fragments, and quite rightly so. The volumes are A4 size which can be rather awkward but works well enough for the purpose. They are not professionally bound (meaning not as by a professional book binder); the binding - which is rather like the way an accountant 'binds' your annual accounts - may well prove to not be as durable as this work deserves. Should there be a fine lady with the 'knight', she is summarily chopped off and never mentioned again, a great pity. There are one or more counties in each volume depending on size of the county from the standpoint of the military effigy count. There is usually one effigy per page although there may be two pages for this purpose if there are a number of photographs. The monuments are listed according to county and then to parish, no rural deaneries or archdeaconries here! For each effigy there is a list of the following: i) location, ii) date, iii) identification iv) position v) length and condition, vi) heraldry v) posture vi) description, vii) references. Position includes where in the church the effigy can actually be found, which is very helpful as I, for one, have sometimes had the unpleasant task of searching behind that odious organ, or other dark and dusty places. A grid reference in location would have been a helpful addition. There is - for me at least - just about enough information - concise, accurate, and brief - as I have no wish to read lengthy, wearisome speculations and baseless theories. Following the list there is a useful - essential actually - glossary of armour terminology; this is followed by excellent line drawings of armour of different times with all the bits clearly labeled. Then comes the inevitable bibliography. The only complete book on this subject. Aidan Dodson The Royal Tombs of Great Britain : An Illustrated History (Duckworth 2004) This is a very comprehensive and well laid out book with a large amount of  illustrations, both photographs, drawings, and

plans, all, perhaps disappointingly in black and white. Some of

the photographs are frankly below standard. The drawings and

plans include those of coffins and their contents and plans of

the burial vaults.

Royal here means ruling monarch; Great Britain

means just that the whole island or parts thereof, even if the

tombs are elsewhere that Great Britain. illustrations, both photographs, drawings, and

plans, all, perhaps disappointingly in black and white. Some of

the photographs are frankly below standard. The drawings and

plans include those of coffins and their contents and plans of

the burial vaults.

Royal here means ruling monarch; Great Britain

means just that the whole island or parts thereof, even if the

tombs are elsewhere that Great Britain.After a useful introduction - more of an overview - part I deals with the several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms; many of the burial sites here are unknown or possible. Actual monuments are few and the majority of these are not contemporary. The mortuary chests in Winchester Cathedral have had the names of the occupant painted several times and the bones are now mix up. See here for information about the mortuary chest inscribed Edmundus Rex, which is described in this book as a son of King Alfred.  Part II deals with England as such, beginning with this time Edgar, yet

another candidate for this role. There are many more surviving

monuments Here Matilda does get a mention and so does the

future French king Louis VIII the Lion who, when prince,

who was invited to England by the rebellious barons to replace

King John; fortunately the latter died and the barons changed

side. So does Lady Jane Grey, and Oliver and Richard Cromwell,

who were no way royal were heads of state. Part II deals with England as such, beginning with this time Edgar, yet

another candidate for this role. There are many more surviving

monuments Here Matilda does get a mention and so does the

future French king Louis VIII the Lion who, when prince,

who was invited to England by the rebellious barons to replace

King John; fortunately the latter died and the barons changed

side. So does Lady Jane Grey, and Oliver and Richard Cromwell,

who were no way royal were heads of state.Part III covers Scotland before the Union with England. The paucity of monument in Scotland is disappointing: for example many of the early kings were buried on Iona but you will find not a single monument there. Finally is shown the grand monument of Mary, Queen of Scots. Part IV takes us to Great Britain, the two countries now having united. The first king listed is George I, who was not buried in England but Hanover. Here are plans and photographs of burial vaults which the common traveller may not visit. The photographs of King Edward VII and George V monuments shows the difficulty of photographing white marble against a dark background. Aidan Dodson is an Egyptologist. |

| Arthur Gardner

Alabaster Tombs of the Pre-Reformation in England.

(Cambridge University Press, 1940) Ernest Arthur Gardner MA FSA (1878-1972) was a writer, art historian, and photographer with a particular interest in medieval sculpture and architecture. ( He is not to be confused with an archaeologist of the same name, his dates being 1862 - 1932.) Arthur Gardner graduated from Cambridge University and joined the family firm of stockbrokers, where he worked for forty years. This life style allowed him the time and the income to follow his particular interests. He learned photography from his father. He travelled Europe and the British Isles photographing medieval sculpture and architecture. These are being digitalize by the Courtald Institute of Arts. This book is divided into two principal sections: text, of 103 pages, and photographs, all black and white of course, on a different, glossy paper, of which there are 305, several per page. This  is presumably because binding in simpler

to set the pages in this fashion, although it is less convenient

for the reader. Arthur Gardner in a very lucid writer and a

superb photographer, especially so, bearing in mind that these

photographs were presumable taken in the 1930's. is presumably because binding in simpler

to set the pages in this fashion, although it is less convenient

for the reader. Arthur Gardner in a very lucid writer and a

superb photographer, especially so, bearing in mind that these

photographs were presumable taken in the 1930's. The first chapter is 'The Alabaster Men' in which we learn what alabaster actually is, a useful beginning as there are basically two types: here we are dealing with calcium phosphate dihydrate or gypsum. Follow the links if you wish to learn about the chemistry.We learn that alabaster is, especially in its purer from, a beautiful, somewhat translucent, material which is rather soft (in the resistance to abrasion sense) and easy to carve: this latter feature is double sided as it has allowed the sculptors to produce magnificent results but also allowed vandals and the careless to damage the monuments. There is then a brief history of alabaster. I notice that Mr. Gardner uses the term gablette for those horizontal canopies surrounding the head of the effigies; there seems to be confusion about this terms as many authors use the term canopy, which is a vertical structure. This is followed by a chapter on Tomb Chests and Weepers and then one on effigies, with sections on portraiture, symbols of rank, colour and posture. Next is a chapter of effigy classification, which has been partly deal within the previous chapter, dealing with them in overlapping periods and the form of dress worn by the effigy, both ecclesiastical, male and female civilian and 'knights'. Next we two appendices: the first is a not that good drawings of armour, which may be helpful in following the text. The second is very useful, being a list of all the alabaster known at the time in table form of several columns: county, class, place, description, attribution (if known or even if not guaranteed), state of preservation, tomb chest, special features, and reference to the illustrations. The author at the beginning tells us there are 342 tombs and 507 alabaster monument, the number difference because husband and wife often share the same tomb chest but have individual effigies. He admits there may be a few more which have escaped his notice. An excellent book, not pocket size but not car boot size either: carry it in your camera bag |

Which are, nevertheless, an excellent source of information about church monuments

Scotland and Wales

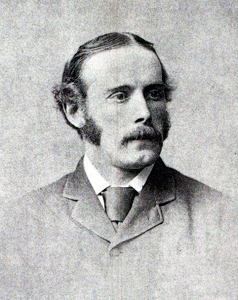

Governments are not noted for their foresight, ability to learn from the past, or the understanding of all the ramifications of what they are about to do. They are the very people who should be capable of this, of course, but their actions, as we have seen only too often, can lead to chaos and even disaster. But occasionally, although unintentionally, their actions can lead to the proverbial 'good thing'. One of these good things was the birth of the Royal Commission of Historical Monuments of England (hereafter RCHM (Eng)). This is how it happened.

In 1882 the government passed the laudable Ancient Monuments Protection Act and this was followed by the even more laudable and wider ranging Ancient Monuments Protection Act of 1900. All very

commendable,

of course, and the

government had the best of intentions in passing these acts but, as

is often

the case, the government had not actually thought it through.

commendable,

of course, and the

government had the best of intentions in passing these acts but, as

is often

the case, the government had not actually thought it through.The problem was that no one had identified quite which ancient or historic monuments should be covered by this protection legislation because the government had not thought about that simple but important point. This was pointed out by David Murray in Archaeological Survey of the United Kingdom (1896) and a little later by Gerard Baldwin Brown (right) in Care of Ancient Monuments (1905). Brown stated what should have been obvious, although clearly had not been so to the government, and that was in order for the legislation to be effective a detailed list of monuments needed to be compiled. The Learned Societies (such as the British Archaeological Association) also lobbied for action to be taken. Gerard Brown proposed that the issues should be addressed by a Royal Commission.

A Royal Commission is an ad-hoc formal public enquiry. It has powers much greater than those of a judge but which are restricted to the terms of reference. It is created by the Head of State (in Britain, the Monarch) on the advice of the government and formally appointed by letters patent. Once begun a Royal Commission cannot be stopped by the government.

Gerard Baldwin Brown's and the Learned Societies' proposal did not go unheeded and a Royal Commission was granted by Royal Warrant in 1908. In that year the Royal Commission of Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, the Royal Commission of the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales and finally the Royal Commission of the Historical Monuments of England were all established with a short interval between the three. Thus the Commission covered Britain but not the United Kingdom. The commissioners were appointed by the various learned societies and other interested bodies and individuals. So the RCHM (England) was born in 1908.

Cut-off dates were set for what was to be recorded: the start date was 'the earliest times', not a limit at all really, but what was the finish date to be? Initially this was set at 1700, a nice round figure, but a later warrant of 1913 reset this this limit to fourteen years later at somewhat awkward date of 1714, the date of the death of Queen Anne, that is, the end of the Stuart dynasty. Of course all dates are quite arbitrary so none can be correct and a later warrant of 1946 gave the Commissioners discretion to go beyond 1714 but with a discretionary terminal date of 1850, a century and a half later than the initial set date. As it was to turn out only one complete county (Dorset) and two towns (Stamford and Cambridge) were to benefit from this later date.

The work started well with the publication of the

very first inventory in 1910: this was Hertfordshire (left)

and was contained in a single volume. And what a work it

proved to be! The work began as

it was to continue for the next ninety odd years with some variations.

Hertfordshire contains St Albans Cathedral: the RCHM would, with a few

exceptions, tend to avoid cathedrals in the future.

The work started well with the publication of the

very first inventory in 1910: this was Hertfordshire (left)

and was contained in a single volume. And what a work it

proved to be! The work began as

it was to continue for the next ninety odd years with some variations.

Hertfordshire contains St Albans Cathedral: the RCHM would, with a few

exceptions, tend to avoid cathedrals in the future. The individual volumes were, until the final days, hardbacks measuring 10¾" X 8¼" and bound in gray or red cloth. The inventories were to be published county by county; for some counties (like the very first Hertfordshire) the inventories occupied single volumes but for others, especially when the cut-off date was extended, they occupied more than one, and some of the volumes were even published in several parts. Each separate volume was concerned with an arbitrary geographical region rather than following the previous one alphabetically so that, unless your geography was first rate, finding an individual village or town could be a little difficult. However it did ensure that the volumes appeared at regular intervals rather than waiting for the whole county to be have been surveyed.

Each book followed a similar pattern. Inside the back cover a flap housed a folded coloured map of the area covered of the relevant county and beautiful coloured folded plans of any cathedral or large building that was being described in the text. There are then several introductory sections, which always followed the same form, before the actual inventory began: i) A list of plans and illustrations. ii) A short preface. iii) Material related to the Royal Commission. This included a list of those monuments deemed 'especially worthy of preservation.' iv) Sectional Preface, this was an overview of what was to follow in the inventory. v) A large (about 70 plus plates) section composed entirely of photographs arranged according to monument type. v) A list of hundreds and parishes of the whole county; those which were in that particular volume were italized. vi) Then the inventory itself, by far the largest section of course. This will be dealt with below. vii) A short list of relevant heraldry viii) A well produced glossary of terms, and finally, ix) The index. This was not sectional.

The inventory proper was arranged in alphabetical order of the individual parishes. Each individual parish, following a general introduction, was then divided into several individual sections, some of which might not always be applicable: these were a) Prehistoric monuments and earthworks. b) Roman monuments and Roman Earthworks. c) English ecclesiastical monuments. d) English secular monuments. e) Unclassified monuments. These sections were further divided into subsections, for example, a church would be divided thus: a) A general introduction. b) The architecture of each part of the building described separately. c) The fittings which were further divided alphabetically into: Bells, Brackets, Brasses and indents, Chairs, Coffin lids or slabs, Communion Table, Doors, Font, Glass, Monuments and floor slabs; not all of these would be present, of course, and there may well be others as the situation required. This was strictly logical but it might be found slightly irritating that church monuments appeared in three different subsections; however if you keep this in mind there is not insurmountable.

The great beauty of these RCHM books were the excellent and large amount of illustrations. There were many photographs, all of a remarkably good quality bearing in mind some of these books are now more than a century old, which occurred, apart from those mentioned above, scattered throughout the book in batches of plates. Then there were drawings, maps (some pull out), plans of the buildings and streets, diagrams all scattered throughout the pages. This was quite the right approach: reading descriptions of a church monument (or anything else for that matter) can eventually become tedious and produce an inaccurate picture in your mind. After all, 'what use is a book without pictures?'

The next county to appear was Buckinghamshire which was published in two volumes, North, and South; these were published 1912-1913. Essex was next and this appeared in in four volumes, North-West, Central & South-West, North-East, and South East. These appeared 1916-1923, there being no pause during World War I. This was a major work with everything proceeding according to plan. Essex was followed by an even more ambitious work when London was published 1924-1930 in five volumes. One volume was devoted to Westminster Abbey alone while St Paul's Cathedral appeared in the volume devoted to the City. The one volume covering Huntingdonshire seemed to sneak in during 1926 in the midst of the publication of the London volumes. Huntingdonshire no longer exists at the time of writing but may make a come back one of these days. This volume did not contain the elusive Soke of Peterborough with Peterborough Cathedral. Herefordshire came next and this was published in three volumes between 1931-1934. This work contained Hereford Cathedral. The work was still proceeding very well and according to plan; you might have felt you would have to wait more than a life time to see the work completed but better that than a rushed and thus inaccurate and incomplete work. In 1936 Westmoreland was published in one volume. Westmoreland also no longer exists being combined with Cumberland (with Carlisle Cathedral) in the 1970's to produce Cumbria. Cumberland was never published. The next volume to be published was Middlesex in 1937. Middlesex was absorbed by neighbouring counties in 1965. They still have a cricket team and remember Denis Compton, however. Following this the RCHM changed their approach somewhat and published The City of Oxford in 1939 as a separate volume; this included Christ Church Cathedral. The County of Oxfordshire was never published. I have no idea how the counties which were to be selected for survey were selected but curiously they were often ones that disappeared during local government reorganization.

Work on the inventories ended with the outbreak of World War II and the RCHM was, understandably, to remain silent for several years after the war.

Then they returned with what seemed like a new confidence and certainly with a flourish. Everything was now as it was before (but even better) and as it should have been. The county inventories continued with Dorset which began in 1952 and was not completed until 1975. Dorset was contained in five volumes, one of which had two and another three parts. This is a magnificent work and certainly their magnum opus. On the shelf the width of all the volumes is a little over 11 inches. A county with no cathedral, of course. These were the first of the RCHM volumes that I bought and they were quite reasonably priced at the time. But was this the beginning of the end of these inventories?

We had become accustomed to complete counties arriving at regular intervals but Dorset proved to be the last to do so. From now on counties were begun but never completed and then eventually the volumes published were no longer in the form of the familiar inventories. The prices increased considerably and I was told by the local bookseller, from whom I bought the volumes, that this was because the government had removed the generous subsidies which had lowered the real cost of these books considerably.

During the work on the Dorset volumes The City of Cambridge appeared in 1959. This was published in two volumes and there was also a box of maps to accompany the books. Again during the Dorset publications two volumes covering parts of the County of Cambridgeshire was published 1968 - 1972. Cambridgeshire was never completed so we were never unsurprisingly to see an inventory of Ely Cathedral.

Another massive work was begun again during the work on Dorset. This was The City of York which was begun in 1962 and completed, well it was never completed; the last volume - Volume Five: The Central Area - was published in 1981. I was living near York at this time and I remember buying Volume Five from a bookshop in Petersgate. I - and almost certainly many others - eagerly awaited the next volume, Volume Six, which would certainly cover the Minster. What did happen is described below.

When the last of the Dorset volumes was published in 1975 the RCHM moved on to Northamptonshire and published several volumes, the last appearing in 1986. However the RCHM seemed somehow to have lost its way as Volume I concerned the Archaeological Sites in North-East Northamptonshire. Volume II was about those in Central Northamptonshire, Vol III in North-West Northamptonshire and Volume IV in South-West Northamptonshire. What on earth was actually going on here? These volumes must surely have been of considerably less appeal than the previous superb inventories and this is borne out by the fact that you can still buy these volumes quite new and in their original unopened box from second hand book dealers. Did someone in authority perhaps deliberately plan these books knowing that they would sell poorly and then announce, with some truth, that the project was losing money so that the RCHM could be justifiably be wound down? Then the RCHM changed its way again: Volume V was Archaeological Sites and Churches in Northampton but this was, for the first time, a paperback volume and, although the churches were listed and described, with the usual drawings, plans and photographs as before, the actual inventories appear on three microfiche sheets in the back pocket with the maps. Unfortunately I have never been able to examine these. Was this volume destined for libraries where there are microfiche readers? If so a paperback binding is really not robust enough for this purpose. In the introduction to this volume it is explained that the book appeared is this form, meaning paperback and microfiche, because of the high cost of hard back book production to the very high standard with which we had become familiar. More paperbacks were to follow but we can be thankful that this was the first and last venture into microfiche. But then in 1985 a RCHM book in the style with which we were familiar arrived: this was Northamptonshire Vol VI: the Architectural Monuments of North Northamptonshire. Not quite as of old: all of the photographs were gathered at the end of the volume rather than some being at the beginning with many scattered through the book, and there was no pocket at the back full of maps and plans. Never mind: they're back! Unfortunately no more volumes appeared.

In 1976 during the production of the Northamptonshire volumes the first - and, as it turned out, the last - of the Gloucestershire Volumes was published: Volume I: Iron Age and Romano-British Monuments in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds. But we never saw any further volumes.

At the same date there were published two town/city inventories: An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford, and Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury Volume I. This latter covered the area of the former municipal borough, exclusive of the cathedral close and its walls and gates, but included Old Sarum castle and cathedral, but not Salisbury Cathedral as was anticipated.

And that was that according to the Google list of counties covered by the RCHM ...although not quite as more were to follow.

Many including myself must have been eagerly awaiting City of York - Volume VI: The Minster. In 1985 there appeared Excavations at York Minster Volume II, followed in 1995 by Volume I. This latter was a very fine publication indeed, consisting of two separate parts in a slipcase. It was also a whopping £100.00! These were all of interest and beautifully produced by the RCHM so we eagerly awaited the inventory volume. It never appeared: instead York Minster: An Architectural History 1220-1500 was published in 2003 no longer by the RCHM but by English Heritage, which had swallowed up the former organization in 1999. An excellent book with superb photographs and drawings, but, sorry I'm afraid this is not what we had been waiting for and just would not do. Volume VI had been in preparation it appears but was never completed.

Wiltshire did not fare well itself but far better than Hampshire, and many other counties, cities, towns and villages, which did not fare at all. I mention Hampshire because I was looking forward to a possible Winchester Cathedral inventory. In 1987 was published a stand alone paperback: Churches of South-East Wiltshire. This was very much in the high standard of the RCHM with superb photographs, drawings, plans, and maps but was not an inventory at all. However the churches were listed and described individually. In the same year was published another Salisbury volume: Salisbury: the Houses in the Close. Again this was a paperback and again the illustrations were of the highest standard. It was followed by Salisbury Cathedral. Perspectives of the Architectural History in 1996; again a paperback and again very well produced: there was even a folded plan of the cathedral in an attempt at a pocket attached inside the rear cover. But worse was to come: in 1999 appeared Sumptuous and Adorn'd: the Decorations of Salsbury Cathedral. Now, apart from the layout following the unsatisfactory thematic form, even the title was quite unsatisfactory too: no longer Salisbury Vol Something. And there was not even a folded map in a pocket: you had to buy the earlier volume for that.

That was the end of those wonderful inventories, their maps, building plans, and photographs. End of an era! Unfortunately there was not even a Friends of the RCHM to protest.

The Pevsner Architectural Guides

These are the books that everyone (or nearly everyone) knows, some people carry around, others even quote from , and if they follow the precedent set by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World, may even swear by. However personally I am more likely to swear at!

The history of the Pevsner Guides is a very different one from that of the RCHM. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner came to Britain as a refugee from Germany in 1930; he was once referred to as a 'Pedantic Prussian' by no less then John Betjeman, who, it is said, was later to write a scathing article about the Pevsner volume on County Durham, referring to the numerous errors and omissions in that volume. Pevsner, it is reported, found that in Britain, unlike other European countries, had little or no information about local architecture, especially for travellers. (Is this actually true? It would seem not to be the case in France, at least, and, in fact, the publishers of the Pevsner volumes replied to me, when I asked that if there were a similar equivalent series in France, that there was not. But see the section on France below.) He must also have been aware of the very comprehensive RCHM volumes which began publication in 1910 (see above) but these are large, heavy volumes (although not academic tomes) and certainly not intended as pocket sized guides. He gained the backing of Allan Lane of Penguin Books, for whom he had written a work earlier, and work began on the Pevsner Guides in 1945. Lane employed two part time assistants (both German refugees) who prepared notes from published sources. Pevsner himself spent his academic holidays touring the country making personal observations.

The first 'Pevsner' appeared in 1951 and this was about the buildings of Cornwall. It is interesting to note that John Betjeman had begun the Shell Guides, sponsored by the oil company and aimed at the up and coming breed of travelling motorists, with Cornwall in 1934.

Each county volume begins with a foreword, and this is then followed by a lengthy introduction which deals with, in separate sections: general, geology and topography, building materials, early architecture, medieval architecture and sculptures, fortified buildings, architecture 1550-1800, small domestic buildings, the 18th-20th centuries including transport and industries, and 19th and 20th century architecture. There is variation on this general arrangement as the situation requires. You will find church monuments alluded to in the relevant sections which avoids having to trawl through the lengthy topographical sections; this is just a rough guide but still very useful.

The Pevsner volumes are very well laid out indeed and the largest section - what we might call the topographical section - is excellent and never descends into thematic mode, as has been done necessarily in the sections of the introduction. The section is arranged alphabetically according to parish which then lists separately the various buildings of interest in that parish. Some parishes have an introduction, where relevant, of varying length. In the larger towns the building list is followed by a perambulations sections (with a clearly drawn map) so you can wander round the town, Pevsner in hand and see for yourself the buildings (in the most general sense of the word) that he describes, as well as showing the world that you are not just a tourist in the most negative sense of that word.

Following the topographical section is a thorough glossary of terms with helpful diagrams, and then a number of separate indices for places, artists etc.

The Pevsner volumes are therefore especially useful for the church monument hunter, being by far the best books to discover the sites of nearly all the church monuments in the British Isles. The simple slabs or tablets, which might have been of no interest to some but, nevertheless, may be of great interest to others are not, of course, included; in fact it would be quite unfair to consider this a serious omission in books of this size. The RCHM series would have been the best source of all - allowing for the cut-off dates - but these were not - and will never now be - completed. As mentioned above each entry for a parish there is a quite distinct church (or occasionally a churches) section and this is further divided into further subsections for general architectural overview, woodwork, stained glass, monuments etc. Note that, unlike the RCHM volumes there is one section for all types of church monuments. Occasionally - but I am glad to say very rarely - a monument is described, presumably because the author considers it 'of importance' (as art historians are wont to say), in the main section rather than later in the monuments list.

Unfortunately, at least in my opinion, these volumes have their faults: as John Betjeman once commented the work has too many errors and omissions. You will find example of the former scattered about the pages of this web site and just one example of an omission is as follows: on the east wall of the south aisle of the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral are three wall monuments all together, being to Mary Wren, Edmund Wiseman, and William Blake. I doubt if many people will know of the first two (I didn't) but many will be familiar with the latter (I was) and even more his poem, And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time. But Pevsner includes only the former two, as to him being more 'important'. Another type of omission seen from time to time is to label a monument, for example, as Gen Ross, without even an initial or a date of death; this may well show carelessness, failure to check details, or that the proof reading is quite inadequate. I get the impression that these volumes were somewhat rushed to publication. I am sure that these errors and omissions will be corrected in due course in later editions but I do find the frequency of them unsatisfactory in what has become a standard work.

While agreeing that the Pevsner series is a fine achievement and very well organized, I dislike the style of the writing in these volumes. The descriptions are far, far too subjective, at times bordering on being arrogantly opinionated and even somewhat offensive. For example we see words such as 'ghastly', 'comic' or 'foolish'; is this really needed in such books? In Canterbury the gilt-bronze effigy of the Black Prince (as all military monuments of that time) is referred to as 'stiff' (hardly surprising with armour of the period!) but nothing about the amazing skill of the medieval craftsmen; while in Ewelm Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk, is referred to as 'looking like a horse'; very droll, of course. What I found particularly irritating when I visited Hereford was the petulant rant about the series of bishops' effigies in Hereford Cathedral: Pevsner may not approve but they are of curious interest and often photographed so obviously some people do find them worthwhile. What is required is an objective list and description of what is being referred to and not one man's unchallenged opinion. Where other writers have taken up the work the style remains unchanged, although the later editions are improving..

Other failures of style I find disagreeable would appear to be a lapse of good manners or even frank rudeness .One which is seen from time to time is this:...tablets by J. Joplin, 1822, and G. Green, 1837 as if the commemorated were of no importance. These books were designed as popular guides to the buildings of England not as an art historian's companion. I feel sure that the majority of people would rather read the names of the commemorated, which are often difficult to decipher owing to fading of the inscription or the height of the monument, rather than a sculptor or mason with whom they are probably quite unfamiliar. Another, which is seen very frequently is this: ...Sir Robert Throckmorton and wife ..., that is not even his Wife, as if his wife were of so little importance or regard that her name is not worth mentioning.

These failings may be forgivable in an inexpensive, popular guide books but Pevsners are not such books: they academic books which have been edited and proof read but not all that thoroughly, it seems.

The Pevsners are being extensively revised by others and many are in the second and a number in their third editions. I hope these criticisms - including the poor manners - will be corrected. For now I have to say that the Buildings of..... is an excellent series but I wish someone else had written it.

In contrast to Britain there is no similar series of books in France which list church monuments clearly and concisely as do the RCHM and Pevsner series. I once contacted the Pevsner publishers to ask if there were such books but was told that there was not.

Hachette's Le Guide de Patrimoine. In the 1990's the publisher Hachette began to publish a series of books on the cultural heritage of France; only four, as far as I can tell, were actually published and then the series

simply appeared to fade away. The aim appeared

to be to produce a series of books similar to the Pevsner

series which itself aimed to - and will eventually - cover the whole of the British Isles, and, in fact, the

Hachette books

were the same size and shape as the later 'elongated' Pevsner volumes.

They appear to have been planned to be published as one volume per

French region, that is the original regions, but only Centre, Isle de

France, Languedoc-Rousillon, and Champagne Ardenne were actually published. Regions are big and were created in 1956, each regions consisting of a

varying number of departments which are, more or less, equivalent to but

generally much bigger than the British counties: for example the

department Pays de la Loire consists of five actual departments. This was

not such a massive undertaking as it would seem at first glance: the

Pevsner volumes list all buildings of note and their contents where

as the Hatchette volumes are concerned only with buildings of

historical interest.

simply appeared to fade away. The aim appeared

to be to produce a series of books similar to the Pevsner

series which itself aimed to - and will eventually - cover the whole of the British Isles, and, in fact, the

Hachette books

were the same size and shape as the later 'elongated' Pevsner volumes.

They appear to have been planned to be published as one volume per

French region, that is the original regions, but only Centre, Isle de

France, Languedoc-Rousillon, and Champagne Ardenne were actually published. Regions are big and were created in 1956, each regions consisting of a

varying number of departments which are, more or less, equivalent to but

generally much bigger than the British counties: for example the

department Pays de la Loire consists of five actual departments. This was

not such a massive undertaking as it would seem at first glance: the

Pevsner volumes list all buildings of note and their contents where

as the Hatchette volumes are concerned only with buildings of

historical interest.The Hatchette volumes are beautifully illustrated. There are photographs, and reproductions of drawings, etchings and engraving as well as many maps, plans and diagrams, all within the text. In fact the series is a visual delight!

However when it comes to the subject of church monuments the Hachette volumes are totally inadequate: church monuments rarely receive a mention at all and when they do it is a brief one in the general text rather than a short separate section. For example, in the Centre volume the lovely monument of Agnès Sorrell at Loches receives little more than a mention and no drawing or photograph at all.

These books are not an adequate source to hunt for church monuments and certainly vastly inferior to the Pevsner volumes in this regard.

This is a massive multi-volume work- almost Victorian in concept - undertaken in the 1960's. There are sixteen volumes covering the whole of France - plus, for good measure, Belgium, Luxenbourg, and

Switzerland - as well as a separate introductory volume. Altogether

there are 10,000 churches included with 7,000 illustrations. This latter

consist of black and white photographs, with a few full pages in full colour, plans, and reproductions of engravings, etchings, and

drawings. Each volume measures 8½" X 11" and the

length of the whole work measured along a shelf is massive 1' 4".

There are about 200 pages per volume. Each volume has a large and

excellent folded map in a pocket in the back, rather like those the RCHM

used to provide.

Switzerland - as well as a separate introductory volume. Altogether

there are 10,000 churches included with 7,000 illustrations. This latter

consist of black and white photographs, with a few full pages in full colour, plans, and reproductions of engravings, etchings, and

drawings. Each volume measures 8½" X 11" and the

length of the whole work measured along a shelf is massive 1' 4".

There are about 200 pages per volume. Each volume has a large and

excellent folded map in a pocket in the back, rather like those the RCHM

used to provide.This is a magnificent work on the subject but actually finding the church you are looking for might present a problem. The books were written before the French government introduced the régions which when sub-divided into their separate départements made the individual communes and their churches very easy to find. The volume shown is titled Auvergne, Limousin, Bourbonnais; the first two were former régions but are no longer individual régions while the latter was a province and never a région at all. To make it even more difficult the volume is not divided into sections corresponding to the three units (for want of a better word) of the title but is an alphabetical list of all the départements in these combined 'units'. However after the main heading of each commune there is bracketed the départment of which that commune is situated. All of which means you will have to do some cross referencing from time to time.

After each commune is listed the names of the church or churches it contains. However this is not divided into subsections as Pevsner and the RCHM, which makes any monument difficult to find. Skimming through the text of 8½" X 11" of book to find a monument is no easy task, especially when one's French is, at the best, described as basic. Monuments are not particularly well featured but, to date, this is the best series of books to find them.

Classes of

Sepulchral Monuments which have been in Use in this

Country from about the Era of the Norman Conquest to the

Time of Edward IV.

Classes of

Sepulchral Monuments which have been in Use in this

Country from about the Era of the Norman Conquest to the

Time of Edward IV. (mentioned opposite) and one of the

Shire Library's series of excellent

pocket books on just about every subject conceivable. As we might expect

it is very well illustrated and generally well produced. There

are 32 pages and a large number of photographs.

(mentioned opposite) and one of the

Shire Library's series of excellent

pocket books on just about every subject conceivable. As we might expect

it is very well illustrated and generally well produced. There

are 32 pages and a large number of photographs. monuments.

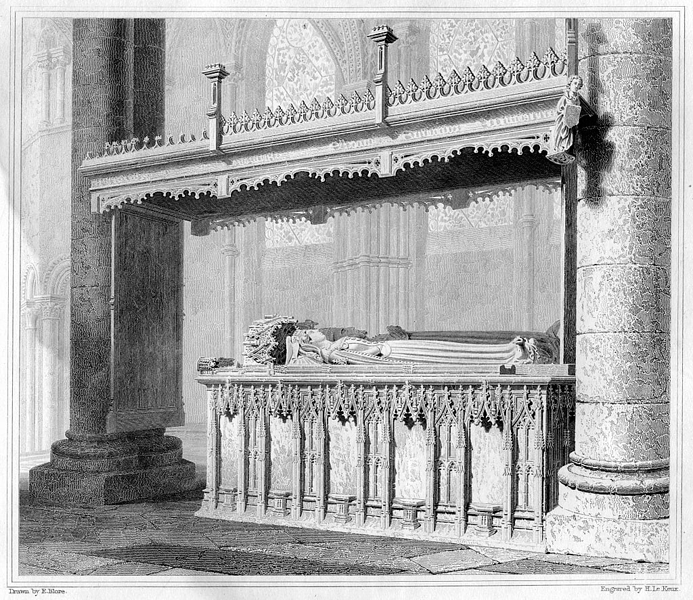

The initial drawings in the churches were executed by

Edward Blore while the engravings were carried out by

Edward Blore himself as well as John and his younger

brother Henry le Keux. Note that these are engravings

rather than etching, the former being a more difficult

and lengthy process to execute than the latter, as is explained

elsewhere. Another difference from the Stothard and

Hollis illustrations is that there are many

engravings of the whole monuments and the surroundings

and not just, as is often the case, the effigy alone,

although these do occur as well.

monuments.

The initial drawings in the churches were executed by

Edward Blore while the engravings were carried out by

Edward Blore himself as well as John and his younger

brother Henry le Keux. Note that these are engravings

rather than etching, the former being a more difficult

and lengthy process to execute than the latter, as is explained

elsewhere. Another difference from the Stothard and

Hollis illustrations is that there are many

engravings of the whole monuments and the surroundings

and not just, as is often the case, the effigy alone,

although these do occur as well. the effigy alone as well as the whole

monument; the last is of Sir Anthony Browne (1548) at

Battle Abbey. There are thirty engraving in all.

the effigy alone as well as the whole

monument; the last is of Sir Anthony Browne (1548) at

Battle Abbey. There are thirty engraving in all.

This books does exactly what its title says: it lists over four hundred and

fifty monuments and burial places of those associated

with the Wars of the Roses, some of which sites, as the author

states in the preface, are conjectural, although every

attempt has been made to be as accurate as possible. It then

lists in alphabetical order of county and then of

parish where these sites and monuments are

located, giving very

full information of the latter, if they still exist;

there is also good information about the commemorated, some of whom may

well be

unknown to those not familiar with this period of

history, while others will be well known to most.

This books does exactly what its title says: it lists over four hundred and

fifty monuments and burial places of those associated

with the Wars of the Roses, some of which sites, as the author

states in the preface, are conjectural, although every

attempt has been made to be as accurate as possible. It then

lists in alphabetical order of county and then of

parish where these sites and monuments are

located, giving very

full information of the latter, if they still exist;

there is also good information about the commemorated, some of whom may

well be

unknown to those not familiar with this period of

history, while others will be well known to most. This is very much

a Victorian book in that it is completist, rather too

much, and there is much speculation; its

style is irritatingly flowery and finally it is

dedicated to Queen Victoria herself. By kings the

author also means queens, as Good Queen Bess

gets a whole section to herself, although the Empress

Matilda does not even get a look in. By England

he means more or less the geographical area called England not

the Kingdom of England as such; so after the Union of

the Crowns under James I, Mr. Wall, although mentioning

this union, still refers to Kings of England, which is

true enough but not the whole truth..

This is very much

a Victorian book in that it is completist, rather too

much, and there is much speculation; its

style is irritatingly flowery and finally it is

dedicated to Queen Victoria herself. By kings the

author also means queens, as Good Queen Bess

gets a whole section to herself, although the Empress

Matilda does not even get a look in. By England

he means more or less the geographical area called England not

the Kingdom of England as such; so after the Union of

the Crowns under James I, Mr. Wall, although mentioning

this union, still refers to Kings of England, which is

true enough but not the whole truth..