The earliest

illustrations of church monuments were produced by

intaglio printing; these are also the most

beautiful. This, of course, was well before the

invention of photography and the first stage involved

drawing by pencil the monument in the church, sometimes

a very difficult task in itself and I greatly

admire the artists who undertook this skillful

work. The image is then transferred onto a metal

plate by creating a number of lines or dots cut

into this plate, the various tones being created

by varying the depth of the line and by cross

hatching. There are other methods and one of

these will be briefly mentioned below. The plate

is then inked and passed though a press to

produce a print. The plate is then

cleaned, reinked and another print made, although eventually the

plate will begin to show signs of wear. Different

artists may be involved in the different processes of

this work.

Can you see a problem here? The image on the

plate has to be drawn in reverse otherwise the resulting print

will itself be reversed. However there are ways around

this problem, obviously, but I will not describe the

minutia here. Three methods of producing the plate will be

described below.

The prints made by intaglio printing are

often loosely - although incorrectly - called

etchings; this latter term, in fact, refers to just

one of several processes by which prints

can be made.

Etching, engraving and

aquatint will be described here but there

are others such as

dry point and

mezzotint; readers of ghost story writer M.

R. James will be familiar with the last term.

There are intaglio processes on other materials,

such as

woodcuts and

wood engravings

but

these will not be described here.

Engraving

In this process

In this process the lines are cut

directly into the metal plate (a steel plate, in the example shown

on the right) by using a tool called a

burin

(left).

The depth of the line is controlled simply by

engraving it more deeply but the direction of the line

is changed by rotating the plate not the

direction of the burin.. A burin as shown, as may be deduced,

has a wooden handle

which is held in the palm of the hand; a number

of different blades are available. This is very

skillful work and a very lengthy process, taking

days, weeks or even months to complete a

plate. Woe betide you should you make a mistake: you

just do not! However the results are truly magnificent:

look at the engraving of King Henry IV and his Queen,

Joan of Navarre, from Canterbury Cathedral on the right. Here the drawing was

executed by architect

Edward Blore, which was a major achievement in itself

and if you are familiar with this monument you will,

like I am, be baffled by how on earth he managed to do it!

As is sometimes the case the another hand carried out

the engraving: here it was

John Henry Le Keux. I certainly admire the skill and

dedication of

these Victorian gentlemen.

I have never attempted engraving and, because I

do not have the skill to do so, the time to develop

that skill, nor a master to teach me, I almost certainly never will. I

have tried to use a burin on softer copper plate which was

easy enough, but to execute a full detailed plate is

certainly another matter.

The plate then has to be printed and this process

will be described below in the

etching

section. Etching was introduced because the

process is speedier and more forgiving than

engraving.

Etching

The term etching

The term etching

strictly refers to the process of cutting the very fine lines in a

metal plate by a chemical process, rather than cutting

them directly with a burin, as is

done

in engraving. As

mentioned above the

finished image, often

called simply an etching, is strictly

a print.

The plates are made of copper, zinc or occasionally

other metals and

the chemicals used - called the

etchant - are

nitric acid, ferric cholide and or, again,

occasionally other chemicals. I use copper

because of its beautiful colour and because it

was used by etchers in the past; ferric chloride

because it is a powder one dissolves in water and this can

be easily sent through the pos. Suppliers and the post

office are probably

more reluctant to send concentrated nitric acid by a similar method!

The

first stage is to clean and degrease the copper

plate otherwise the ground will not stick. The

ground

is a waxy like substance which is melted onto the

plate while it lies on a hot bed which is heated by gas or

electricity. Then this layer of this ground is

rolled so that it is absolutely even. The ground is to

prevent the etchant biting into the plate: you

will soon be 'scratching' through the ground (a

process called

needling), so exposing

the underlying copper and this is the first

stage in creating the actual image. The back of the plate

may already be covered in a resistant layer but, if

not, a liquid ground or varnish must painted on to

prevent the etchant from biting the

copper on the back of the plate.

Next you

smoke the ground by holding the

still warm grounded plate over smoking tapers or a

candle.

(shown below, left) This is great fun and makes you feel you are

using a centuries old technique, which of course you are,

and not tapping on a keyboard, as I am doing at

the moment. The purpose of this is to give the

ground a blackened appearance so that it is

easier (more visible) to draw on and so

needle the plate. Oh, and don't

forget to turn off your smoke alarm: Rembrandt and

Stothard didn't

have one!

Then the drawing

Then the drawing

is transferred to the plate by the following

process: you first make a tracing of, for

example, your pencil drawing of an effigy. This

need only be an outline tracing as only the

general proportions need to be copied. You then

turn the tracing paper over and lay it on the

grounded plate with a sheet of

trace down

paper between them (white or yellow, is

best), remembering to place it the correct way

up. You then draw with a pencil over the lines

you made on the tracing paper (but on the other

side!). Trace down paper resembles old fashioned

carbon paper in allowing images or text to be

copied onto the

paper, in this case the grounded plate, below so you will find there is an

outline, white or yellow, of the reversed drawing on

the ground over the copper. This reversed

drawing will

print the correct way in

due course.

Now we have a problem: the reversed drawing on the

ground is mainly in outline but you need to fill

in the detail and shading from your non-reversed

drawing. So now you can cheat and return to the

21st century but only for a while: scan your

drawing into the computer, reverse it and then

print the reversed image. Computers, scanners,

and printers do have their use, after all, but

if you are tired of things not working and

screen messages you cannot understand, work

through a mirror as did the etchers of old!

Now we are ready to

needle the plate:

scratching though the ground to expose the

underlying copper, being guided by the lines

made by the trace down paper and the reversed

image you somehow prepared. Try to just go

through the ground and not cut into the soft

copper, or errors will be more difficult to

correct. Here you draw the image outline and

detail with all the shading by a variety of

cross hatching; you cannot at this stage alter

the depth of the line (this will come later) but

you

can make it wide or narrow. An etching

needle is shown below right, but there are other

designs available.

When ready

When ready the plate is immersed in the

etchant - usually nitric acid or ferric chloride - for a measured length of time - several minutes

- and then removed. It is then washed and

examined. If you want the lines deeper to give a

stronger line on the forthcoming print the other lines

are

stopped out by painting a liquid varnish

over these lines. The plate is then returned to the

etchant bath and again left for several minutes but this

time the etchant will only bite into the lines which

have not been stopped out. This process may be repeated

several times, etching deeper and deeper lines. This

process requires a good deal of experience to

develop the necessary skill.

Initially the copper plate is

inked: the aim is to cover all of the plate

with ink and especially to force the ink into all of the

etched lines on the plate. Etching ink is very thick and

this work

is carried out with the copper plate placed on a heated

bed. Black ink is shown here but other colours are

available. You can also produce coloured prints with

different coloured inks

but this technique is beyond the scope of

this short article and certainly well beyond my skill!

This is very messy work!

Next you wipe the ink off

again! Well, not all of it just that which is on the

surface of the plate and not in the etched lines. This

is a difficult procedure as if any ink is left

on the surface you will end up with a dirty

looking background (that is, if you

want

it white, as in the etching of effigies)

when you come to produce the first print: and

then you will have to wipe all of the ink off

the plate and start all over again. There are

various techniques for removing all the surplus

ink from the plate, one of which is to wipe it

with the side of your hand, rather like brushing

crumbs off the table for someone else to Hoover

up!

|

|

| Inking the Plate |

Wiping the Plate |

Now you are ready to print the plate:

the copper plate is laid on the bed of the etching

press, which is a special rotary press rather like an old

fashioned mangle, protecting the bed and blankets with clean paper to

avoid any ink marks. This is then covered by the dampened

printing paper, then by a protective paper layer

and a series of thick blankets to even the

pressure from the rollers. You turn the wheel

and the bed with the plate and the paper passes

between two rollers. This can be quite hard

work but the large and very heavy press in operation in the photograph is

geared to make the work easier.

Etching

paper is quite thick and needs soaking in water

for a period before printing can be done.

The plate, paper

and protective layers on the bed of the

press thus travel to the other side of the

rollers and now

is the moment of truth. In the penultimate

photograph below our etcher has thrown back the

blankets, which passed through the rollers with

everything else and is just about lift the

protective layer from the paper underneath. You

can see the image showing through the damp

paper. In the final photograph, she lifts the

damp paper away from the copper plate and

there is the image. Success! Note that the image

covers the whole plate so this does not need to

be wiped completely clear of ink as when trying to

achieve a white background such as in etchings of

effigies.

If you are not happy with the result, or if

you want another print...or another, you clear

off all the remaining ink from the plate and start again.

|

|

|

|

| An Etching Press |

Turning the Wheel

The Work Appears at the Other End |

Lifting the

Protective Paper Which Keeps the

Blankets Clean

You Can See the Back of the Work Thru

This Paper |

Lifting the paper

back and showing the printed image.

The copper plate is below |

If you think about it - you are printing from a metal

plate with ink

in fine lines, not a

raised surface and you are using damp paper: it

shouldn't really work or at least not so as to

produce such fine effects: but it does!

Other Methods

.jpg) There are other ways

There are other ways

of producing plates for intaglio

printing which you are much less likely to come

across and these may be found on the internet in

articles about intaglio printing

,

if you are interested.

I will

mention just one other

method

here, not because I have or have

.jpg)

ever seen original prints produced by this

method, but

because it is a

technique that I have

used

myself on two or three occasions; this is called

aquatint. This

method,

although related to etching, produces

prints which resemble pencil drawings rather

than those produced by etching, which

resemble

pen and ink drawings. It is

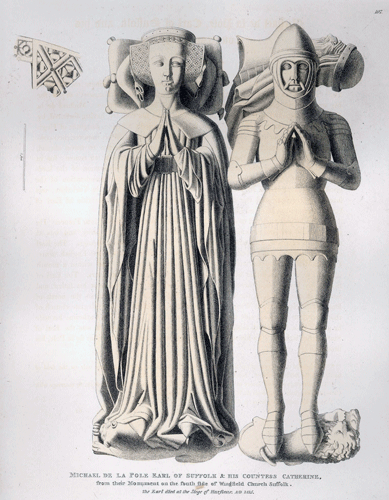

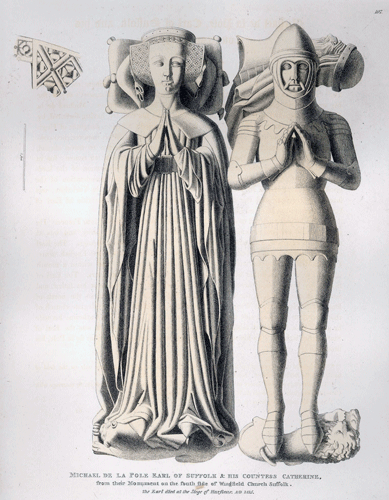

difficult to see at this magnification but

compare the image on the left, which was

produced by aquatint, with that on the right,

which was produced by etching. On the left the

tones are solid blocks of shading while on the

right the difference in tone is produced mainly

by cross hatching but also by different

depths of the incised line. This latter process,

produced by using different times in the etching

bath, is actually similarly used in aquatint

although for whole blocks rather than individual lines.

Aquatint can be combined with etching to produce

a line and wash effect: this was used on the

print on the left.

The method of aquatint is, in outline, thus: again you

begin with a clean, grease free copper plate but

this time instead of covering the plate with a

melted, solid ground, it is

covered with powdered

rosin, a solid

form of resin obtained from pine and other

plants; rosin is also used by violinists and

ballet dancers. The aim is

to spread this rosin powder evenly and

completely

over the copper plate. This is difficult to do

well but there are

aquatint boxes to

carry out this process so as to achieve the

desired result; these can be operated by turning

a handle manually so spreading the powder but

there are also mechanically driven ones. These

boxes are expensive to buy: my limited aquatint

work was carried out in a professional studio.

It is possible to spread the rosin powder by a simpler and

considerably cheaper method. The rosin powder is

placed in a silk bag and simply shaken over the

plate; I have never used this process but it

rather sounds like one of those procedures which

is considerably easier said than done. It does

have one advantage in skilled hands: with the

box the rosin is evenly spread but with a silk

bag, it is possibly to vary to amount of rosin

over different areas of the plate. This may

produce interesting (and possibly

unpredictable) effects but my interest is to

simply produce a record rather than any

artistic effect.

This spreading of rosin powder

will simply dust the plate

but the rosin will not adher to it, so

the plate has to be taken (with great care:

eject the cat, turn off the fan, and close all doors and windows!)

to the heated bed which is used for melting the ground in

etching

.

The plate is then warmed until the

white rosin dust begins to melt and turns

yellow; it is then removed before the rosin

completely liquifies and spreads over the whole

plate. Th

is result will

produce nothing! What you are trying to achieve

are dots of rosin spread evenly over and fixed

to the plate.

The desired

apperance are tiny islands of rosin

grains with bare metal between them

.

If

you now etch the plate in

the acid bath the result will be tiny tiny

raised islands of unetched metal, which have

been protected by the rosin, surrounded by a sea of etched and

so very slighly lower bare metal.

If you now ink

the plate as before, the ink will

remain

in the 'sea' while the 'islands' with

be bare uninked metal

,

and

the printed result a uniform gray area

depending on how long you have left the plate in

the etching bath. Actually it will not really be

uniform at all but rather like a

photograph in reverse: the 'islands' all white

(the paper) and the 'sea', which holds the ink

like the etched or engraved line, a shade of gray.

But like a photograph, unless a very grainy one,

it will look a flat gray. Not very exciting but

now if you use stop out varnish as in the

etching process, the stopped out areas will

appear white and the other areas, depending on

how long they are in contact with the etchant,

will turn out to be increasingly darker shades of

gray. The aquatint on the left was begun with a

line etching for the outlines and the aquatint

used later for the shading.

Note that

several of the etchings you may find in

the works of Stothard and T & G Hollis appear

coloured; although coloured etchings can be

produced by a technique using different coloured

inks, these are not the method used in those works.

Rather they are hand coloured etchings, each

print being hand coloured after they were

printed. Actual coloured etching is beyond the

scope of this article and quite beyond me as

well.

| The

Artists |

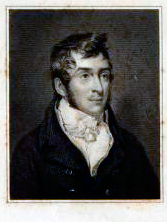

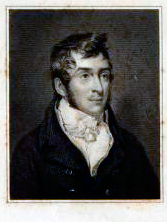

Charles Alfred Stothard (1786-1821)

was the son of the painter

Thomas Stothard RA

by his wife, Rebecca Watkins; incidentally Thomas was

the son of a publican and was born in the Black Horse

Inn, Long Acre,

Charles Alfred Stothard (1786-1821)

was the son of the painter

Thomas Stothard RA

by his wife, Rebecca Watkins; incidentally Thomas was

the son of a publican and was born in the Black Horse

Inn, Long Acre, London.

In 1807 C. A. Stothard was admitted as a student of the

Royal Academy and in 1811 exhibited his first historical

painting. In the same year he published the first part

of what was to be the twelve part work, The

Monumental Effigies of Great Britain. Charles himself

executed the pencil drawings of all the monuments in the

various churches and subsequently reproduced the majority

of them as etchings. The

artwork was accompanied by information about the

monuments themselves and those they represented. Charles Stothard died before the work was completed

so the etchings in the last two parts were executed from

his drawings by other artists. All the parts were bound

in a hefty book with an introduction, including a life

of the artist by

Alfred John Kempe, his brother in law, in 1832. London.

In 1807 C. A. Stothard was admitted as a student of the

Royal Academy and in 1811 exhibited his first historical

painting. In the same year he published the first part

of what was to be the twelve part work, The

Monumental Effigies of Great Britain. Charles himself

executed the pencil drawings of all the monuments in the

various churches and subsequently reproduced the majority

of them as etchings. The

artwork was accompanied by information about the

monuments themselves and those they represented. Charles Stothard died before the work was completed

so the etchings in the last two parts were executed from

his drawings by other artists. All the parts were bound

in a hefty book with an introduction, including a life

of the artist by

Alfred John Kempe, his brother in law, in 1832.

In 1809 Charles Stothard made the acquaintance

of Alfred John Kemp, a fellow antiquarian, who would later

assist with the text of

Monumental Effigies. Alfred Kemp was the son of a

bullion porter at the mint and had a sister Anna Eliza

to whom Charles became devoted.

In 1815 the artist was employed by

Daniel Lysons to produce drawings for the latter's

topographical work, Magna Britannia, and he

journeyed throughout England to carry out this work. While

he was away Mr. Lysons procured Charles the post of

historical draughtsman to the Society of Antiquaries in

London. In 1816 he was employed by that society to make

drawings of the of the Bayeux Tapestry. At this time the

tapestry (actually not a tapestry at all but rather an

embroidery) was stored in a roll on a drum which was

unwound for visitors; today the display is more

convenient for visitors!

The artist made three journeys to post-revolutionary

France, these being in 1816, 1817, and 1818, where he

sought the effigies of the early Plantagenets. It had

been assumed that these effigies had been destroyed

during the French Revolution, when there had been a wave

of destruction of monasteries and churches, rather

similar to that during the

Dissolution of the Monasteries in England in the 16th

century. The burial place of four of the early

Plantagenets was at Fontevraud Abbey (Maine-et-Loire) and

here Charles discovered the effigies of Henry II; his

wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine; their son, Richard the Lion

Heart; and their daughter-in- law; Isabelle of Angoulême,

the wife of their son, King John. The Abbey had been

turned into a prison by Napoleon but the artist

discovered the effigies preserved in a 'cellar' there. I

am uncertain what is meant by 'cellar': this may refer

to the Romanesque Kitchen (similar to the one at

Glastonbury, England) or to one of the underground

passages with which the Abbey abounds. He also travelled

to L'Epau Abbey near Le Mans (Sarthe) where Berengaria

of Navarre, wife of Richard the Lion Heart, had been

buried. This abbey had been converted into farm

buildings but Charles Stothard discovered Berengaria's

effigy there too; this must have been during the 1816

visit, as he records that he returned the following year

to make a drawing. At Le Mans itself he made a

drawing of the enameled plaque that had originally hung

over the tomb of Geoffrey Plantagenet in Le Mans

Cathedral; I do not know where he found this monument

but it is now preserved in the new museum in that city, Le Carré Plantagenêt.

He also visited Caen

(Normandy) to record the tombstone of Queen Matilda,

wife of William the Conqueror, which presumably was, and

still is, preserved in the Church of the Trinity there. All

of these drawings were converted into etchings by Charles

Stothard himself and may be seen The Monumental

Effigies of Great Britain.

In 1816 the artist also visited Paris

where he made a drawing of the effigy of Bernard du

Guesculin, then at the Museé des Monuments.

This effigy was originally at St Denis

and has now been restored to that cathedral. The story

of the destruction and recovery of the monuments is

described in the Paris page of this

website. In 1817 he visited

Chartres Cathedral (Eure-et-Loire) and recorded

two of the standing figures on the south door, and on

the same trip he visited Compiègne (Oise) and

recorded a medieval effigy there; I have not been able

to locate this effigy to date.

Many French monuments had been

destroyed but many

had not. Perhaps the French were more careful with

their cultural heritage than were the

English, and especially the Scots, but, more likely,

people had become more sensitive to their heritage during

the three hundred years between these two waves, as well

as valuing things for their historical and artistic worth

rather than destroying them for what they assumed they

represented. So we can thank Charles Stothard for

discovering these effigies and to

at least have contributed to their preservation, and the

fact we may see them today. It is

to be regretted that his own monument at Bere Ferrers has not received

the same care, the inscription being now virtually obliterated.

In 1818 Charles

married Anna Eliza Kemp

and his new wife accompanied him on a final (1818) visit

to France; his wife wrote a detailed account of their

journey, and so began her career as a

writer. They first journeyed through Normandy and visited

the church of Our Lady and St Laurent at Eu

(Seine-Maritime), where they descended down a ladder

into the unlit crypt through a hole in the pavement of

the nave. The monuments were originally in the body of

the church but only the effigies survived destruction,

being thrown into the crypt. The artist recorded

three of these monuments there, although there are now

several more, all restored and which may be seen in the crypt, now lit and accessible via a staircase.

The Stothards visited Rouen, Paris and then

Bayeux (Calvados) where the artist completed the

drawings he had begun earlier, of the famous tapestry,

aproject that he had taken him three years.

They left Normandy and travelled into Brittany,

seeking two effigies of the Dukes of Brittany at

Ploermel (Morbihan), which had been moved to an

Ursulines Convent. Charles executed three drawings of

these two effigies; they were later moved in 1821 to St Armel's

Church, where there are now two further effigies. Next they visited Josselin (Morbihan)

where they found the effigies of Oliver de Clisson and

his wife Marguerite de Rohan, which were badly damaged

with several fragments in a garden. The artist executed

a drawing of these effigies, which are still in

the Basilique Notre-Dame-de-Roncier in the town.

The next place visited was Vannes where, in the ruins of

the Church of the Cordeliers, the couple discovered two

broken effigies, one being of Arthur Duke of Brittany

-1 (c. 1330) and Charles duly recorded them.

The effigy of Arthur is said to have been repaired and

on display but to date I have been unable to locate it.

He did not only draw monumental

effigies but other sculpture and views of the

environment as has been indicated above. At some point

the couple must have visited St Maurice's Catherdral at

Angers (Maine-et-Loire) where Charles recorded the

figures around the doorway.

These drawings of French effigies were intended to

be included in a further book, a companion volume to

The Monumental Effigies of

Great Britain,

although some of the etchings in that latter book

did include effigies he had recorded in France: these

were relevant, being of members of the Norman and Angevin houses of England's ruling families. This

unfortunately was never to be, although Anna Eliza did

keep his drawings in an album or albums. These were

dispersed at some later time, possibly following her death. Two

albums of drawings of monumental effigies came up for

auction several years ago and were published in the

Journal of the Church Monuments Society. (Vol.XIII

1998). I do not have access to the original drawings but

I will add my own pencil drawings of them to this site in

due course.

In 1819 the drawings of the Tapestry were completed and

presented to the Society of Antiquaries together with a

paper on the dating of this magnificent work. Later that

year the drawings were published and Charles Stothard

elected a Fellow of the Society. In 1820 the artist

worked on the ninth part of The Monumental

Effigies and in the autumn of that year the couple

visited the Netherlands.

In 1821 Daniel Lysons commissioned Charles Stothard to

visit Devon to make drawings for the Devon volume of

Magna Britannia, so he left London on May 16th, rather

reluctantly without his wife who was now in the later

stages of pregnancy. He worked at Linton, Coombe Martin

and Ilfracombe, travelling mostly by foot; he reached

Atherington - where he made drawings of the excellent

double monument on May 24th. He spent the night

of the 25th - a Friday - at Hatherleigh, where his

journal ends.

He arrived at Bere Ferrers on the Sunday

afternoon, so had spend all of Saturday travelling, a distance of some thirty miles.

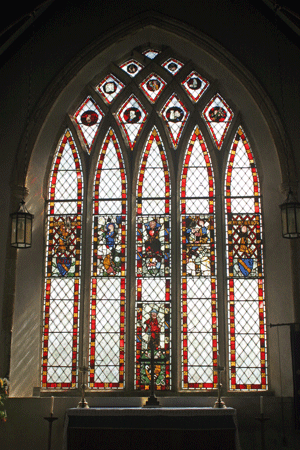

He met the Rector

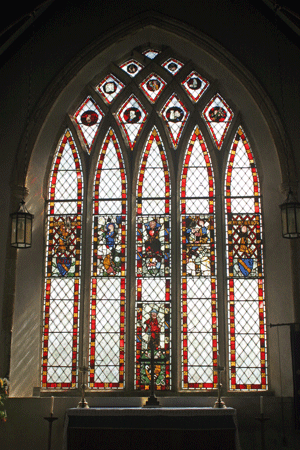

-2, Mr. Henry Hobart, in the churchyard of

the parish church, St Andrews. I

know the route well and it is quite possible that

Charles

Stothard, who was young and clearly very fit, could have

walked all the way. The Rector give permission to the

artist for his project which was to draw the stained glass

window at the east of the chancel, even borrowing a

ladder from a local gardener and arranging for it to be

set up in St Andrew's for Charles to begin work

on Monday morning; furthermore he invited the artist to

stay at the rectory for as long as he needed to complete his

work.

Charles Stothard began his work as planned at ten

o'clock the following morning. The Rector arranged

for his curate, a Mr. Servante, to accompany the artist

to the church and remain with the artist a short time to

make sure he had everything he required. At two o'clock

in the afternoon Mr. Servante visited the church to see

how the work was progressing: the ladder at this time

was in its original position, to the north of the altar

but the artist indicated he would soon be moving the

ladder to the opposite side. The Rector was visited by

the local doctor and he was asked by Mr Hobart to call

into the church to see how the work was progressing and to

remind the artist that dinner at the rectory was taken at

five in the afternoon.

However, the artist was destined never to return to the

rectory as the doctor found him lying on the floor,

unconscious but still alive. It was discovered that the

ladder had sustained a broken rung and that the artist

had fallen and struck his head on the slab with the

effigies of a knight and lady which was nearby. Within three

minutes of the doctor's arrival Charles Stothard died.

Mr. Hobart attempted to trace Charles Stothard's family,

and found an envelope in the artist's pocket on

which was written the name and address of a London

publisher, to whom he wrote a letter explaining what had

happened. Bere Ferrers is a remote village by road and

must have been even more so 200 years ago, so Mr. Hobart

explained in this letter to initially go to Plymouth and

take a boat up the River Tavy to 'Beer Church Town', as

it was delightfully known then. The publisher replied

two days later to say the artist's father, Thomas Stothard, had left for

Plymouth that morning.

The inquest found no suspicious

circumstances and it must be added that the gardener, a

heavily built man, from whom the ladder was borrowed,

stated that he had been using it regularly. The artist

was buried on the 4th June that year: his grave stone

and further information is shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

.png) |

| Above

left: St

Andrew's in Bere Ferrers

where Charles Stothard was accidentally killed.

Above right: The brass plaque marking

the place where he died. Near right:

The stained glass window he was drawing when he

fell. Center right: The chancel at Bere

Ferrers. The plaque can just be made out in

front of the monument. Centre left:

Charles Sothard's grave stone in the church yard

below the window he was drawing. The stone is

very eroded and now virtually illegible, from the wind, rain and spray from

the River Tavy. The stone is now resting on the

ground and clamped to the church wall. There are

no official burial records but various notes

indicate this this is the site of his burial. I

presume a path has been excavated around the

church. Far left: Etching of the

monument in the chancel. |

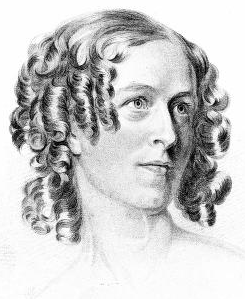

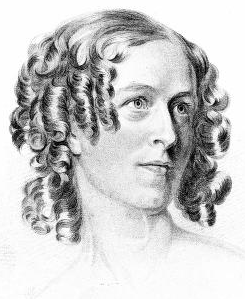

Anna Eliza Stothard, Charles's widow, gave birth to a

daughter, Blanche, on 29th June 1821, just a

month after her husband's

death. Sadly the little girl died at six months of

age on the 2nd of February the following year. Anna

Eliza and her brother, Alfred Kempe, to whom I have

alluded above, completed the work on Monumental

Effigies, now using other artists to prepare and

print the plates from the drawings that Charles had

executed. These artists included Charles's brother,

Robert Stothard, and Edward Blore, the architect, who

has been mentioned on these pages. The etchings of the

double monument at Atherington, which Charles Stothard

had drawn on his Bere Ferrers trip, was etched by one C.

J. Smith.

I find it curious to relate that Anna Eliza

Stothard married Rev. Edward Bray, the Vicar of

Tavistock, the year following her husband's death. We

cannot know the exact circumstances of this, we never

shall, but she mentions in a letter, very peculiar

events. During this second marriage she continued

and developed her writing career, which included

topographical works, biographies, novels and romances.

She returned to London after her second husband's death

and died at the grand age of 93.

-1 I assume that this

effigy is of Arthur II, Duke of Brittany, who died in

1312. The is confirmed by comparing the drawing, by an

unknown artist, on the right to Charles Stothard's

drawing of Duke Arthur; although the work shown is

nowhere near as finely executed, they are similar enough

to be considered to represent the same man. As mentioned, although this

effigy, seems to have been badly damaged when the

Stothards visited, it is said to have been restored

,although I have been unable to locate it. Unfortunately

I do not have access to the original Stothard drawings.

-2 The rector of Bere Ferrers is given the curious title of archpriest.

In earliest times the archpriest was the head of the priests

of a diocese and an archdeacon was the head of the

deacons; the meanings of these terms and the function of

their offices has changed over the years with an archdeacon

now having jurisdiction over an archdeaconary, a

subdivision of a diocese. An

archpriest is now just a curious - and rare - title,

although there are associated privilages. An

archpriest had a supervisory roll - but not jurisdiction - over

a number of priests, with the archpriest being the

priest of the principle parish, in other words with a

similar funtion to the modern rural or area

dean. The number of archpriests diminished over the

years, especially following the Reformation, until now

there appear to be only two, at Bere Ferrers and at

Haccombe, also in Devon. The title of archpriest was

confirmed as late as 1913. In theory the archpriest is

not under the authority of the bishop but only

acknowleges the Archbishop of Canterbury although, in

actual practice, the usual procedure of the church

heiarchy is followed. The title archpriest does not

follow the incumbent should he move to another parish,

but remains with the parish.

I was

given a course in etching by my wife as a birthday

present, at a studio near Gunnislake in Devon which, by a

curious coincidence, was about six

miles from Bere Ferrers.

George Hollis (1793-1842) & Thomas Hollis

(1818-43) Father and son who began work on what

was to be a continuation of Charles

Stothard's

Monumental Effigies of Great Britain in 1839,

following the premature death of the latter. For

example, Charles Stothard never executed an etching of

Richard II and Anne of Bohemia, in Westminster Abbey,

but these are included in the Hollis collection; whether

Charles Stothard had intended to do so, or perhaps he

made the preliminary drawings only, I do not know. George is

described as an engraver and his son, Thomas, as a

painter and draughtsman. Initially Thomas executed the

drawings while his father made the etching plates.

George died in 1842 so then Thomas continued the work

alone, executing the original drawings as well as making

the plates. Unfotunately Thomas died of

tuberculosis the

following year at the early age of twenty-five so

the work was never completed. I am afraid I have no

images or or further information about this father and

son.

Their work was published in a similar form to that of

Charles Stothard but there is no accompanying text.

|

Pencil drawing is an excellent method for

producing good, accurate renderings of church monuments,

especially

while in

the church. This is what the etchers, such as Charles

Stothard and Thomas Hollis, used to do all those years

ago in order to produce preliminary drawings for their finished work. I

use a series of pencils from hard to soft with which it

is possible to produce clear lines and good shading.

Highlights can be added by using a plastic eraser to

lighten the shaded area. But pencil drawings, no matter

how fine they may look, do not reproduce particularly well on the

internet. Compare the drawing on the left of the lady at

Wear Gifford, on the banks of the River Torridge in Devon,

which I drew in the church around twenty years ago with

the pen and ink drawing on the right, which I produced

at home more than forty years ago. However having seen

Charles Stothard's original pen drawings, I think I

shall have to sharpen my rechnique!

Pencil drawing is an excellent method for

producing good, accurate renderings of church monuments,

especially

while in

the church. This is what the etchers, such as Charles

Stothard and Thomas Hollis, used to do all those years

ago in order to produce preliminary drawings for their finished work. I

use a series of pencils from hard to soft with which it

is possible to produce clear lines and good shading.

Highlights can be added by using a plastic eraser to

lighten the shaded area. But pencil drawings, no matter

how fine they may look, do not reproduce particularly well on the

internet. Compare the drawing on the left of the lady at

Wear Gifford, on the banks of the River Torridge in Devon,

which I drew in the church around twenty years ago with

the pen and ink drawing on the right, which I produced

at home more than forty years ago. However having seen

Charles Stothard's original pen drawings, I think I

shall have to sharpen my rechnique! I

executed this drawing of Prince William of Hatfield,

young son of King Edward III, by copying an etching by

Charles Stothard. The lady in Wear Gifford is under a

very low arch and behind the choir stalls and so is

difficult to draw and not easy to photograph well from a

good angle. William of Hatfield is in an

even more difficult position in York Minster so how Mr.

Stothard produced his original drawing is quite

amazing.

I

executed this drawing of Prince William of Hatfield,

young son of King Edward III, by copying an etching by

Charles Stothard. The lady in Wear Gifford is under a

very low arch and behind the choir stalls and so is

difficult to draw and not easy to photograph well from a

good angle. William of Hatfield is in an

even more difficult position in York Minster so how Mr.

Stothard produced his original drawing is quite

amazing.

could

correct a mistake, remove a blot and, especially

useful, gently scratch the line with a scalpel to make it

less black which makes the drawing, as may be seen,

resemble an etching. If you removed an error there would

still be a usable

drawing surface below. The surface itself takes a fine

line without it bleeding: some papers are almost like drawing

on blotting paper in this respect. I used to scratch out with a number 15

Swann-Morton blade, then use an ink eraser or stick and

finally polish the paper with a pencil eraser.

could

correct a mistake, remove a blot and, especially

useful, gently scratch the line with a scalpel to make it

less black which makes the drawing, as may be seen,

resemble an etching. If you removed an error there would

still be a usable

drawing surface below. The surface itself takes a fine

line without it bleeding: some papers are almost like drawing

on blotting paper in this respect. I used to scratch out with a number 15

Swann-Morton blade, then use an ink eraser or stick and

finally polish the paper with a pencil eraser.

When ready the plate is immersed in the

etchant - usually nitric acid or ferric chloride - for a measured length of time - several minutes

- and then removed. It is then washed and

examined. If you want the lines deeper to give a

stronger line on the forthcoming print the other lines

are stopped out by painting a liquid varnish

over these lines. The plate is then returned to the

etchant bath and again left for several minutes but this

time the etchant will only bite into the lines which

have not been stopped out. This process may be repeated

several times, etching deeper and deeper lines. This

process requires a good deal of experience to

develop the necessary skill.

When ready the plate is immersed in the

etchant - usually nitric acid or ferric chloride - for a measured length of time - several minutes

- and then removed. It is then washed and

examined. If you want the lines deeper to give a

stronger line on the forthcoming print the other lines

are stopped out by painting a liquid varnish

over these lines. The plate is then returned to the

etchant bath and again left for several minutes but this

time the etchant will only bite into the lines which

have not been stopped out. This process may be repeated

several times, etching deeper and deeper lines. This

process requires a good deal of experience to

develop the necessary skill.

.jpg) There are other ways

of producing plates for intaglio

printing which you are much less likely to come

across and these may be found on the internet in

articles about intaglio printing,

if you are interested.

I will mention just one other

method

here, not because I have or have

There are other ways

of producing plates for intaglio

printing which you are much less likely to come

across and these may be found on the internet in

articles about intaglio printing,

if you are interested.

I will mention just one other

method

here, not because I have or have.jpg) ever seen original prints produced by this

method, but because it is a

technique that I have used

myself on two or three occasions; this is called

aquatint. This method,

although related to etching, produces

prints which resemble pencil drawings rather

than those produced by etching, which

resemble pen and ink drawings. It is

difficult to see at this magnification but

compare the image on the left, which was

produced by aquatint, with that on the right,

which was produced by etching. On the left the

tones are solid blocks of shading while on the

right the difference in tone is produced mainly

by cross hatching but also by different

depths of the incised line. This latter process,

produced by using different times in the etching

bath, is actually similarly used in aquatint

although for whole blocks rather than individual lines.

Aquatint can be combined with etching to produce

a line and wash effect: this was used on the

print on the left.

ever seen original prints produced by this

method, but because it is a

technique that I have used

myself on two or three occasions; this is called

aquatint. This method,

although related to etching, produces

prints which resemble pencil drawings rather

than those produced by etching, which

resemble pen and ink drawings. It is

difficult to see at this magnification but

compare the image on the left, which was

produced by aquatint, with that on the right,

which was produced by etching. On the left the

tones are solid blocks of shading while on the

right the difference in tone is produced mainly

by cross hatching but also by different

depths of the incised line. This latter process,

produced by using different times in the etching

bath, is actually similarly used in aquatint

although for whole blocks rather than individual lines.

Aquatint can be combined with etching to produce

a line and wash effect: this was used on the

print on the left. Charles Alfred Stothard (1786-1821)

was the son of the painter

Charles Alfred Stothard (1786-1821)

was the son of the painter

London.

In 1807 C. A. Stothard was admitted as a student of the

Royal Academy and in 1811 exhibited his first historical

painting. In the same year he published the first part

of what was to be the twelve part work, The

Monumental Effigies of Great Britain. Charles himself

executed the pencil drawings of all the monuments in the

various churches and subsequently reproduced the majority

of them as etchings. The

artwork was accompanied by information about the

monuments themselves and those they represented. Charles Stothard died before the work was completed

so the etchings in the last two parts were executed from

his drawings by other artists. All the parts were bound

in a hefty book with an introduction, including a life

of the artist by

London.

In 1807 C. A. Stothard was admitted as a student of the

Royal Academy and in 1811 exhibited his first historical

painting. In the same year he published the first part

of what was to be the twelve part work, The

Monumental Effigies of Great Britain. Charles himself

executed the pencil drawings of all the monuments in the

various churches and subsequently reproduced the majority

of them as etchings. The

artwork was accompanied by information about the

monuments themselves and those they represented. Charles Stothard died before the work was completed

so the etchings in the last two parts were executed from

his drawings by other artists. All the parts were bound

in a hefty book with an introduction, including a life

of the artist by

.png)