The

Musings of a Monuments Man

The

Musings of a Monuments ManPosted 28th February 2021: The Key and the Stone Beware the Organ Tuner! Psst, Want Some Lead, Guv? Bats in the Belfy What's the Difference between a Cathedral and a Museum? Conington or Conington

Posted 7th March 2021 : Locked and Barred Tales of Three Locked Churches (The PeepToe Mail; The Pretty Girl Holds the Key; Private Property: Keep Out!) No Reply?

Posted 15th March 2021 Praise to the Postie We Shall Have Music Wherever We Go Seeing a Saw Horse

Posted 24th March 2021: Tales of Three More Locked Churches (The Never Open Door; Locked In; Wot, No Vicar) Bequests The Watch That Ran Backwards

Posted 9th May 2021: How to Set Off Alarms! Tales of a Another Three Locked Churches (Sling Your Hook; Digi-Tramps and Dog Walkers; No Way In)

Posted 1st March 2022: Excitement! Tales of a Further Three Locked Churches (A Lucky Find; Church: What Church? Best Viewed from Outside) A Strange Hotel Not Strictly

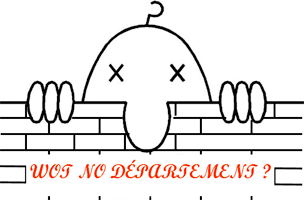

Wot, No Church? Roads, Maps and Road Maps Tales of Three Yet More Locked Churches (The Church & The Mairie 1, The Church & The Mairie 2, The Church & The Tourist Office)

To while away the hours during this virtual house arrest imposed upon us by those attempting to fight the Covid Pandemic and when I cannot visit churches to take photographs and none have been sent me me recently, I have begun this blog to amuse myself and hopefully others. Some of these items do appear elsewhere on this site but I thought might fun to gather them together and expand them a little on one page. Other items are new and more will be added later.

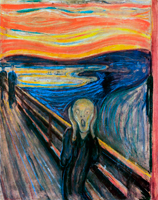

I am asked from time to time why do I drive around taking photographs of church monuments; why didn't I photograph those subjects that appear in photographic magazines such as landcapes, sport, wildlife, pets, flowers, portraits or children. You might win a prize too! Some of these are excellent from both the esthetic and technical points of view but they simply do not hold any great interest to me. Architecture might be an interesting subject to pursue particularly industrial architecture, street photography too but I do not have the skill nor the Leica of Henri Cartier-Bresson, and surrealism (my favourite art form) if only I knew where to start!

Hunting church monuments takes us to some interesting and beautiful villages, towns and cities which otherwise we would never have visited; there have been one or two not so pleasant ones from time to time but these are very rare. St Albans is a very fine small city that comes to mind, unspoiled by brash shop fronts and the almost inevitable 'chains', Wingfield in Suffolk, Pamber Prior in Hampshire, Framlingham in Norfolk, Bures in Suffolk (church and chapel), Aldworth in Berkshire with a fascinating collection of effigies in the church and the best pub so far, and Catterick in North Yorkshire which has the best chip shop we have discovered to date. If nothing else I am an expert on chip shops. Our daughter lives near Ely, a small city with free parking, a useful raiway station, good pubs, and those rare things: art shops and independent bookshops which are among the best too; and then there's the Cathedral, so empty your piggy bank! But there is one pub to challenge that at Aldworth and that is the Holly Bush in Potter's Crouch: I do not know if there is a church with fine monuments or even a church but this is a pub I would go on a hundred mile tour to visit. Unfortunatley the land lord has recently moved so I hope the standards he set remain in place.

One of the delights of English villages - which I regret to say French villages do not share - is as well as a church there is always a pub nearby, and often a very fine one serving the best of English 'pub grub' and the best real ale. I really enjoy the simple - and often the most reasonably priced - French cuisine with a glass of Southern French red wine, but I look forward to these tit-for-tat restrictions being lifted so we can cross the Channel and enjoy a pint of Old Peculiar with steak and kidney pie, proper chips and mushy peas (no other veg). Some villages have hardly anything but a church and a pub and I remember 'up north' pubs were often next to churches in industrial towns and were dubbed 'churches with chimneys': worshippers began their day in the one and then sojourn to the other for different sort of spiritual refreshment.

We meet some delightful and interesting people on our trips often, but not always, connected with the churches we are visiting. I used to meet many vicars and rectors some years ago but this is rare now with the introduction of team ministries where the lead cleric is known (although it might be said historically incorrectly) as the Team Rector. I now more often deal with administrators, parish clerks, churchwardens, and other lay folk. However I recently wrote to a vicar in Suffolk asking permission to visit and photograph in his church and his friendly reply also recommended The de la Pole Arms opposite the church for lunch, adding that we might have to book on 'Fish Friday'. The church was one of the most interesting with an excellent series of monuments and so was the de la Pole Arms who provided superb pub grub and real ale. In fact we returned a few months later with our grandchildren and met the Vicar quite by chance in the pub, a delightful and friendly man indeed.

So here we go at my first attempt at blogging. Any thoughts, ideas, comments and moans are welcome, moans less so, of course.

| The Key and the Stone |

Years ago, long before the internet or even personal computers, I

wrote to the 'Vicar or Rector', as I would at that

time, of a church in

Hampshire, asking permission to visit the church and take

photographs of the monuments. What I did not know was that the

church in question no longer served a parish so there was

neither vicar nor rector any more, it

being, what was then rather tactlessly known as, 'redundant'.

Incidentally such churches, which are still used at times for

worship, were cared for by the Redundant Churches Fund

which in 1994 changed its name to the more polite Churches

Conservation Trust. But the absence of a vicar was no problem as the ever resourceful

Post Office

delivered my letter to the person who acted as key holder of this

church. I was later to find many times that the Post Office and the

wonderful postmen and women have far more intelligence and

ability than the internet with all its fine resources. The caretaker

then

replied and asked me to telephone him to arranged an appointment to visit his house and collect

the church key. I did so and he told me that if I arrived at 10.00 am on the day

arranged I would find the key under a large stone on his door

step.

Years ago, long before the internet or even personal computers, I

wrote to the 'Vicar or Rector', as I would at that

time, of a church in

Hampshire, asking permission to visit the church and take

photographs of the monuments. What I did not know was that the

church in question no longer served a parish so there was

neither vicar nor rector any more, it

being, what was then rather tactlessly known as, 'redundant'.

Incidentally such churches, which are still used at times for

worship, were cared for by the Redundant Churches Fund

which in 1994 changed its name to the more polite Churches

Conservation Trust. But the absence of a vicar was no problem as the ever resourceful

Post Office

delivered my letter to the person who acted as key holder of this

church. I was later to find many times that the Post Office and the

wonderful postmen and women have far more intelligence and

ability than the internet with all its fine resources. The caretaker

then

replied and asked me to telephone him to arranged an appointment to visit his house and collect

the church key. I did so and he told me that if I arrived at 10.00 am on the day

arranged I would find the key under a large stone on his door

step.I always arrive early and this day was no exception: It must have been around 9.30 am or so. I stopped outside the house and there was the stone on the door step. I walked up the short drive only to find there was no key under the stone; I knocked on the door only to received no answer. I sat in my car but nobody arrived at the house and the door never opened. At 10.01am I retraced my steps along the drive, lifted the stone and there was the key. Perhaps someone knows something that I do not! The church, by the way, was quite a small one and across a muddy field; if there was a drive either I did not find it or it had become obliterated with time. The tomb was very large and nearly filled the chancel. I returned the key through the letterbox as requested and drove home. I can no longer accurately remember the key holder's name: it may have been Dumbledore, Merlin or something like that. |

| Beware the Organ Tuner! | |

Tea with the vicar is rare these days but years ago,

when I began visiting churches, I was occasionally invited into

the vicarage for a cuppa. I wrote

to a vicar in Hampshire with my usual request and he replied asking me

to called at his house for a cup of tea before Tea with the vicar is rare these days but years ago,

when I began visiting churches, I was occasionally invited into

the vicarage for a cuppa. I wrote

to a vicar in Hampshire with my usual request and he replied asking me

to called at his house for a cup of tea before visiting the

church. Actually, these short visits are a very tactful and

polite way of assessing those who wish to visit the church; and in this case, as will be seen,

it was not without good reason. The Vicar told me that his church

had been robbed recently and there had been a number of

similar robberies in

other churches in the area. He then told me, with both delight

and some surprise, that all of the items taken from the

churches had been recovered and returned. It seems that the

person who had stolen them had not done so for any real personal gain

by somehow selling them himself or to a receiver of stolen goods; the

latter, from past experience, are often 'respectable' second hand book dealers or antique

dealers, who clearly do not ask the questions they ought to ask

and freely display the goods in their shops. Rather this

particular thief actually collected church artifacts,

just as people collect stamps, coins, vinyl records, cheese

labels, cigarette cards, slide rules and just about anything,

even things which can hardly be conceived as being collectable.

I once visited a house of a lady who collected vintage prams:

the house was somewhat difficult to walk around.

visiting the

church. Actually, these short visits are a very tactful and

polite way of assessing those who wish to visit the church; and in this case, as will be seen,

it was not without good reason. The Vicar told me that his church

had been robbed recently and there had been a number of

similar robberies in

other churches in the area. He then told me, with both delight

and some surprise, that all of the items taken from the

churches had been recovered and returned. It seems that the

person who had stolen them had not done so for any real personal gain

by somehow selling them himself or to a receiver of stolen goods; the

latter, from past experience, are often 'respectable' second hand book dealers or antique

dealers, who clearly do not ask the questions they ought to ask

and freely display the goods in their shops. Rather this

particular thief actually collected church artifacts,

just as people collect stamps, coins, vinyl records, cheese

labels, cigarette cards, slide rules and just about anything,

even things which can hardly be conceived as being collectable.

I once visited a house of a lady who collected vintage prams:

the house was somewhat difficult to walk around.And the person who collected these items did so very easily as he was regularly given the church key, had plenty of time to spare, could park a van outside without questions being asked, and had every right and reason to be in the church as much as the lady who arranged the flowers: he was the organ tuner!

|

| Psst, Want Some Lead, Guv? |

When I was quite

young - certainly less than eleven - a friend and

I decided to

become junior rag and bone men: we would knock on front doors

and ask whoever appeared if they had any jam jars. We would

collect quite a number and when we could carry no more, we

would go along to 'Suggie's Yard', the premises of the local

scrap dealer, and sell them for a few pennies, maybe even a

shilling or two, especially if we managed to find some lead as

well.

We indeed did collect lead, although I can no longer recall from

where: we probably found it lying about in one of the many

derelict houses we used to explore, on waste land we combed, or

even by excavating the local rubbish tips. Yes we were junior

'golden dustmen' or rather 'leaden ones'! I have to stress we never removed it

from the church roof, but others, it seems, clearly have more

courage and less conscience. When I was quite

young - certainly less than eleven - a friend and

I decided to

become junior rag and bone men: we would knock on front doors

and ask whoever appeared if they had any jam jars. We would

collect quite a number and when we could carry no more, we

would go along to 'Suggie's Yard', the premises of the local

scrap dealer, and sell them for a few pennies, maybe even a

shilling or two, especially if we managed to find some lead as

well.

We indeed did collect lead, although I can no longer recall from

where: we probably found it lying about in one of the many

derelict houses we used to explore, on waste land we combed, or

even by excavating the local rubbish tips. Yes we were junior

'golden dustmen' or rather 'leaden ones'! I have to stress we never removed it

from the church roof, but others, it seems, clearly have more

courage and less conscience.I visited a church in Berkshire some years ago now where the Vicar apologized for the state of the church, telling me that they had just had the lead stolen from the roof and that this was the second occurance within months: so hence the cold and damp state of the church interior. The cheek and the challenge of removing lead from a church roof is really quite astounding: church roofs are very high, often covering a large area and, although lead is a very soft metal and relatively easily rolled, it is also very heavy indeed. How do these people get onto the roof in the first place and then lower the rolls of lead onto the ground without being spotted? How do they manage to carry out their work and not be heard? This is hardly a quick, casual theft: it must be carried out by organized gangs with ladders and lorries. They presumably carry out their work at night so must use lights and probably fairly powerful ones too. To whom do they sell the lead? I find it quite amazing that they are rarely discovered and apprehended. Our local church in Devon did not have its lead removed but during the day of one Christmas Eve, its oil tank was emptied as were those of several houses in the area who used oil fired central heating. Parishioners were told to arrive well wrapped and were issued with blankets for the Midnight Service on this Christmas Eve. This wasn't someone with a jerry can opening a tap: this again was a gang with an oil tank lorry and the equipment to pump out the oil. Again were these thieves were never spotted or challenged? Where were the Devon and Cornwall police or neighbourhood watch? Churches do have their spies, and I am glad that they do, so it is amazing that the above can ever happen, especially in daylight hours. I went into a church in a small village in Devon to draw a double effigy. It's an interesting church with a very tall thin tower, which may be seen for miles around, as well as there being a number of interesting monuments. The church is is in the centre of the village and when I had finished my drawing I went for a cup of coffee and a snack in a small café , which was attached to a shop directly opposite the church. The proprieter, who served me, told me that he had seen me going into the church but not coming out again, so was just going to see if I were all right. Actually he really meant 'if I were up to no good!' His tact was superb and he did not ask to carry out a bag search! We are lucky that people do keep an eye on our churches but even if no one specifically does, does no one observe anything unusual? So it is quite amazing that a church can have its lead roof stripped and a oil tank lorry can arrive and pump out the heating oil from the tank during the day and nobody observes it. |

| Bats in the Belfry (In More Senses Than One!) |

A few years ago we visited a church in Bedfordshire where we were met by the Vicar, a very friendly and helpful man, who let us into the church, rather curiously, via a locked door leading into the vestry and then through another door into the chancel. The chancel was screened off from the nave by a large heavy duty, clear plastic sheet closed with a zipper which could be opened to enter the nave. All the monuments, pews, lectern, pulpit and other furnishings were covered in thick protective sheets. The Vicar explained that the church had become infested with bats and that, as we knew, bats were a protected species and could not be eliminated or evicted. Bat excrement causes erosion of stonework and spreads disease to human beings (including the Covid virus and rabies) and hence, in this case, all the vulnerable surfaces were covered and services thus had to be held in the chancel where the bats had not and now could not enter. The Vicar allowed us to remove the coverings and take photographs and then left us alone, saying that it did not matter about the vestry door being left unlocked as he would return later in the day to lock it himself. We did find a suitable box, unfortunately unlocked, to give a well deserved 'offering'. An even more severe case occured somewhere in Yorkshire but I only have second hand knowledge of this. Here the church had become so infested that people had actually become ill owing to the bat excrement and services could no longer be held at all anywhere in the church. Services were now held in the church hall instead. I cannot help but think it is nonsense that people should be driven out a church where their ancestors had worshipped for centuries because of wild animals or rather by the absurd laws protecting them. There is considerable more concern about our environment in recent years and rightly so: I am sure no one would like to experience air you could taste and sometimes could hardly see though and rivers full of filth rather than fish which I recall as a young child. But we must get the balance right between the environment and the people in it. There are many, often give the title of 'environmental activists', who push this balance far too far in the wrong direction. Bats are interesting, fascinating creatures, the only flying mammals now around, and I certainly would not like to see them become extinct. But we cannot drive people out of their churches because bats have taken up residence: they can - and will - always find an alternate home elsewhere; or one can be provided nearby with bat boxes in trees. |

|

What's the

Difference between a Cathedral and a Museum? Answer: Museums are

Free! |

||

|

That 'joke' is not entirely fair - none of this short article actually is - as museums often have ways of making you pay, such as charging an entrance fee, which often is not a modest one, to visit special or promoted exhibitions. Museums receive grants from the Government for their upkeep while cathedrals, as well as other churches, do not; also cathedrals, especially the large, fine medieval ones we visit are very expensive indeed to maintain, whereas I should imagine that most of our museums are not. In 2013 the Minister concerned with the matter of cathedral charges replied in Parliament to a question about this very subject, stating that of the forty two English Cathedrals only nine charge an entrance fee. The information is several years out of date now and I do not know the current situation . It certainly seems to be more than this charge entrance fees and if you want to know why, read on!  The cathedrals that

do charge are: Canterbury, Coventry,

Ely, Exeter, Oxford (but they cheat by only charging to go

into the college, rather than the cathedral itself which anyway in the

college precincts), The cathedrals that

do charge are: Canterbury, Coventry,

Ely, Exeter, Oxford (but they cheat by only charging to go

into the college, rather than the cathedral itself which anyway in the

college precincts), St Paul's, Winchester, and York Minster.

Other non-cathedral churches also charge for entry: St Bartholemew the Great,

London; Holy Trinity, Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire; and St

George's Chapel, Windsor, although the last takes a leaf out of Oxford's

cheat book and charges to go into the castle grounds where the Chapel

is situated. Westminster Abbey (once an abbey, then a cathedral

for a short time, but now now a collegiate church) has the

dubious reputation of being the most expensive church in the

world to visit. The first thing to note about this list is that

these cathedrals are some of the 'tourist' cathedrals and the

majority are large medieval churches. The forty-two cathedrals

include those such as Blackburn, Bradford, Chelmsford,

Wakefield, and Derby, which, in all fairness it must be said,

are not generally regarded as 'tourist' cathedrals and I image

quite a few people did not realize that there are

cathedrals in some of these places. This distorts the figures by

making it appear that there is a smaller proportion that charge

than it would seem if the 'non-tourists' cathedrals were not

included. St Paul's, Winchester, and York Minster.

Other non-cathedral churches also charge for entry: St Bartholemew the Great,

London; Holy Trinity, Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire; and St

George's Chapel, Windsor, although the last takes a leaf out of Oxford's

cheat book and charges to go into the castle grounds where the Chapel

is situated. Westminster Abbey (once an abbey, then a cathedral

for a short time, but now now a collegiate church) has the

dubious reputation of being the most expensive church in the

world to visit. The first thing to note about this list is that

these cathedrals are some of the 'tourist' cathedrals and the

majority are large medieval churches. The forty-two cathedrals

include those such as Blackburn, Bradford, Chelmsford,

Wakefield, and Derby, which, in all fairness it must be said,

are not generally regarded as 'tourist' cathedrals and I image

quite a few people did not realize that there are

cathedrals in some of these places. This distorts the figures by

making it appear that there is a smaller proportion that charge

than it would seem if the 'non-tourists' cathedrals were not

included.I need to add to this list The Temple Church, London, although a charge is a recent change of policy and the fee is a very modest one. When I did visit the Temple Church to take photographs a while ago, they did not charge me at all: had they read the nice things I had written about them on these pages, was it because I was taking photographs, had a nice smile, or (hopefully not) because I'm a bit old? Anyway I put a little more than the £3 entrance fee in the box; perhaps they are more devious than I thought! Where are the other 'big' cathedrals that are not on the list such as Peterborough, Salisbury, Norwich, Lichfield, Durham, Ripon, and Southwell? These are the cathedrals that ask for voluntary contributions. I cannot remember any pressure being put on me to make such a contribution at Peterborough, Lichfield or Ripon and at Norwich, in particular, the request was a very polite one and the suggested fee a modest one. Sometimes the pressure on visitors is said to be rather excessive: I have heard that this is the case at Salisbury where the 'request' is quite intimidating one visitor wrote, as well as the suggested fee being a high one. So if a robed figure approaches you with bell, book and candle - pay up! I seem to remember that Southwell did have a compulsary charge and quite a low and curious one but it may well have been a voluntary one and I had not realized; there was also, rather curiously, a higher fee for photography. I thought that Tewkesbury Abbey had been omitted from the list because when I visited this fine church there appeared to be an entrance fee; had they seduced me into paying a voluntary fee perhaps? Durham Cathedral does not have a compulsary entrance fee but asks for a voluntary contribution of £5 per person and report that the average they actually receive is 32p. If visitors receive the quite unjustified unfriendly welcome that we received several years ago, I have to add that I am hardly surprised. However I understand that the situation in Durham has changed fairly recently. Quite a few people complain bitterly about these compulsory charges; some categorically refuse even to visit cathedrals that charge entrance fees. I do have some sympathy with this view. Places of worship they might be but they are still very expensive to maintain and someone must pay the bill. I think there is certainly justification to complain about the sometimes excessive charges, especially when you realize that it is per person, as well as the unpleasant pressure said to be put on visitors to make a 'voluntary' donation, which often features a suggested amount, itself sometimes quite a high one. Again there is a kinder side to these charges: some cathedrals allow free entry for certain purposes - obviously for worship but other reasons also - as well as at certain times, such as early morning and late evening. There are concessions too for children and students for example. What I do find objectionable, if not frankly insulting, comes from the website of a Cathedral whose charges are not only high but, on top of this charge, there are a number of extras too. I will not name this cathedral but at one point their website states that if you cannot afford the charges then speak to someone at the desk who will give you a sympathetic ear. Imagine anyone actually carrying out that embarrassing request. Do you have to take along a DHSS certificate, a pension book, or three years' audited accounts perhaps? Or do you just say that you are very sorry but you are poor. On the same website no one less than the Dean himself writes that it is quite free to attend services; I find this a quite extraordinary statement to make. What the Dean failed to mention is that you may not be charged on your way in but there will be a 'voluntary' charge one on your way out. Let us try to step outside this situation and put it into perspective. As I have said many people object to cathedral entrance charges, but why? Do people object to paying because a cathedral is a place of worship, which should be freely open to all, surely. But the majority of people are not visiting the cathedral primarily, if at all, to worship, but to enjoy seeing the building with all its many magnificent features: in other words, they are sightseers not worshippers. On the other hand people appear to be quite happy to pay to visit stately homes and often join, at no small cost it must be added, organizations such as the National Trust, so for members some of these places may be visited free. After all the majority of cathedrals are free to visit while I do not think you can visit any stately home free of charge. The medieval cathedrals were built effectively for all and the building design and work was overseen by a master mason, a man who had no formal education but learned his trade by experience; perhaps these cathedrals are all the better for that! However there was an element of trial and error and sometimes the buildings, or parts of them, did fall down! The tower at Ely is one example. Stately homes, on the other hand, were built for the very few to live in ease and opulence and designed by a qualified architect. Personally I would much rather visit a cathedral; in fact, I have no wish to visit stately homes at all. Think for a moment what each of them teaches you. The majority of people do not share my view which is maybe why Downton Abbey continued for at least six series (plus specials) whereas The Village and The Mill were each cut after two.

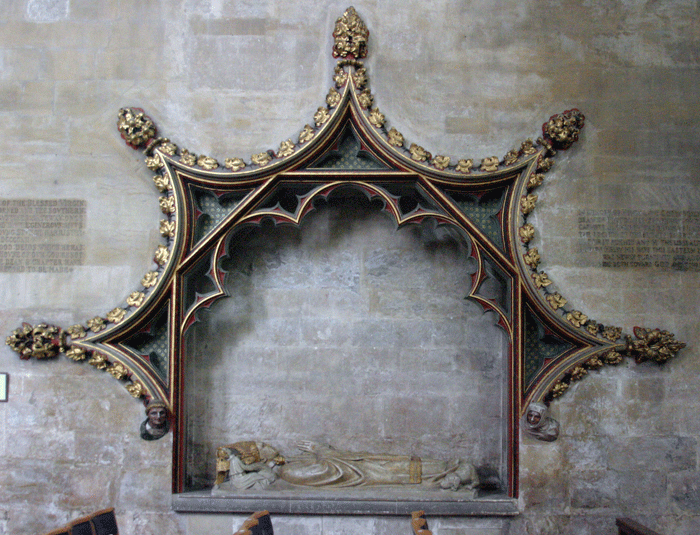

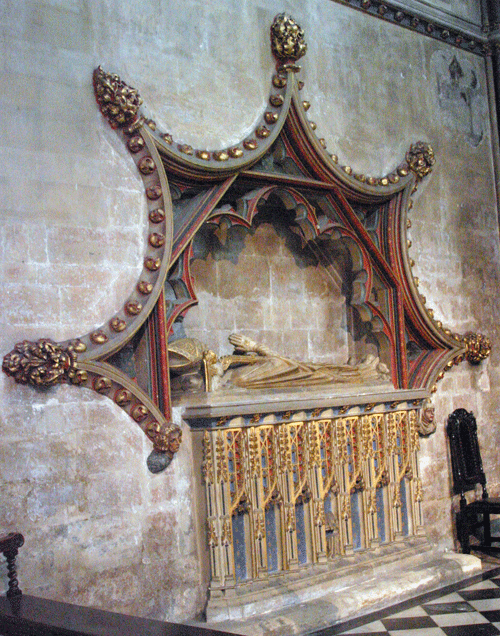

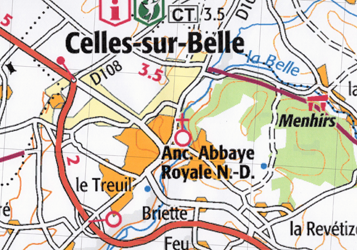

In France the situation is reversed: the museums all charge an entrance fee while the cathedrals - or at least those I have visited - do not, although there are exceptions to this general statement. Even Notre Dame in Paris, probably France's most well known cathedral, is free to enter but there are charges to visit the tower (€8.50) and the crypt (€6.00); both costs are more than covered if you buy the Paris Pass, which allows you free entry to a number of other places in Paris as well, including the Louvre. However the Paris Pass costs €130 per adult for a two day pass, so you may exhaust yourself trying to recover this cost in visiting enough places! Chartres is also free to enter as is Reims, but both charge a relatively small fee to visit certain parts of the building: the crypt and tower (Chartres) and the the treasury (Reims). The Louvre, the magnificent museum in Paris is €12 per person, but is well worth the cost. If you can tolerate the queues, you can stay all day (in fact you would need to stay more than all day to see it all) and the food on site is excellent and reasonably priced; my experience of English museum food is rather the reverse. Other than cathedrals every French church we have visited has been free and donation boxes are rare. One church, an interesting country church, was in a very poor condition, very damp and with a collapsed roof in a side room but there was no donation box anywhere to be found: I should like to have contributed €5.00 but there was nowhere to put it. Incidentally French churches are maintained by the state, mostly better than this example. The first thing that struck me about French cathedrals, and many churches, apart from their fine architecture is their wonderful height, so much higher than an English church of similar ground area; this proportion was most disturbing at first . The second thing was that they are virtually empty: it took me two days to photograph and record the monuments in Exeter Cathedral but only half an hour to record those in Cahors Cathedral. But they are not just empty of monuments, they seem to be empty of other things too: welcome desks (sometimes a euphemism for pay counters), books shops, coffee shops, and people, both clerical and lay, as well as those robed guides who abound in English cathedrals. What they do sometimes feature are beggars on the steps ascending to the principal entrance door who often kindly offer to open it for you. We haven't been to all French cathedrals: it would take some time there being rather a large number of them, but two particular examples we have visited spring to mind. St Denis is situated in a northern suburb of Paris and about six miles from the centre, so it means a ride on the Metro to a station of the same name if you stay in the city. It is not only a cathedral but was the burial place of the French kings and members of their families; I use the word was here as the large majority were ejected from the tombs during the fury against royalty during the Revolution and thrown into a common pit. Later, after the fortunately temporary restoration of the monarchy, they were 'resurrected' and buried in ten separate coffins in a charnel house in the crypt of the church; it must have been a difficult, if not impossible, task to carry this out as the remains had been buried in quicklime directly in the earth. Several churches in Paris and elsewhere were demolished during the Revolution but many of the monuments were rescued (by antiquarians not by royalists) and eventually found there way to St Denis. So, in effect, St Denis is is a museum as well as a cathedral and, as you might expect, the church is free to enter but there is a charge to visit the area where all the monuments are situated. Incidentally unlike the situation in Westminster Abbey, photography in not only allowed but quite free.  The other is the cathedral at Nantes, once the capital of Brittany which somehow found its way into Pays-de-la-Loire, and which contains the magnificent tomb of Duke François II and his wife, Margurite de Foix. Not only is the Cathedral quite free to visit, and photography free, but a platform has been built above this monument to allow photography at an excellent angle. There were some friendly guides too (no robes) to show you around the crypt, which has a magnificent exhibition of the history of the building - all free. In England sometimes, even if there is an entry fee, there are then more extras to visit the crypt, the tower, the gallery etc - more extras than buying a car years ago.  The

Abbey of Fleury at St Benoît-sur-Loire is now, once again, a real working abbey

staffed by Benedictine monks and, while not a cathedral, is a

most interesting church to visit. In the crypt there is a

reliquary containing the remains of the founder of the Order, St

Benedict himself, although this is disputed by the monks of

Monte Cassino in Italy. The church also contains the effigy of Phillippe

I, known as 'The Amourous', who died in 1108 and in whose

unusually long reign occurred both the Norman Conquest and

the First Crusade. Not only is the church free to enter but when we

visited it was open from 6.00 am until 10.00 pm; there is no

charge for photography although they politely ask you not to

take photographs during the services. This must be one of the

most welcoming churches ever. Now there's an idea: England should

perhaps undissolve the monasteries; we know where all the money

went! The

Abbey of Fleury at St Benoît-sur-Loire is now, once again, a real working abbey

staffed by Benedictine monks and, while not a cathedral, is a

most interesting church to visit. In the crypt there is a

reliquary containing the remains of the founder of the Order, St

Benedict himself, although this is disputed by the monks of

Monte Cassino in Italy. The church also contains the effigy of Phillippe

I, known as 'The Amourous', who died in 1108 and in whose

unusually long reign occurred both the Norman Conquest and

the First Crusade. Not only is the church free to enter but when we

visited it was open from 6.00 am until 10.00 pm; there is no

charge for photography although they politely ask you not to

take photographs during the services. This must be one of the

most welcoming churches ever. Now there's an idea: England should

perhaps undissolve the monasteries; we know where all the money

went! |

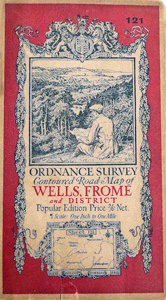

| Conington or Conington - or - In Praise of the Ordnance Survey |

||||||

| It may not look quite right but there is no double n in Conington; and Conington as well, for that matter. Why make it easy when you can make it difficult!

The Sat Nav has become in many cars just a

normal fixture, rather like seat belts, electric windows, radios, air

conditioning, servo-brakes, and power assisted steering. When I

bought my first car these features, if available at all, were

referred to as

extras - except of course the Sat Nav which was then a just a

dream to those, like myself, who dreamed of such things.

Sometimes I wonder how I ever managed to find new places at all without

this wonderful invention. The Sat Nav maps are not as complex and

hence nowhere near as helpful as Ordnance

Survey maps but could not serve their purpose if they were

so.

The Ordnance Survey maps are far too crowded with detailed

information for a driver to both follow and drive at the same time,

but

excellent for a passenger skilled at navigation. I also have a

hand held Sat Nav loaded with the1:50 000 Ordnance Survey maps of Britain complete

with all the, sometimes quirky, details, marking all the

churches and even indicating if it has a tower, spire, or

neither. How big is the church is not

shown. The screen is necessarily small so it can be easily held.

A few years ago in Nottinghamshire we were trying to find a

place called Owthorpe but the car's SatNav had never

heard of such a place, which has a population of less than one

hundred people. This was no problem as there it was on the

Ordnance Survey Sat Nav, located with the very extensive index;

this device does not give spoken guidance but a navigator can

use it with no difficulty.

The Sat Nav has become in many cars just a

normal fixture, rather like seat belts, electric windows, radios, air

conditioning, servo-brakes, and power assisted steering. When I

bought my first car these features, if available at all, were

referred to as

extras - except of course the Sat Nav which was then a just a

dream to those, like myself, who dreamed of such things.

Sometimes I wonder how I ever managed to find new places at all without

this wonderful invention. The Sat Nav maps are not as complex and

hence nowhere near as helpful as Ordnance

Survey maps but could not serve their purpose if they were

so.

The Ordnance Survey maps are far too crowded with detailed

information for a driver to both follow and drive at the same time,

but

excellent for a passenger skilled at navigation. I also have a

hand held Sat Nav loaded with the1:50 000 Ordnance Survey maps of Britain complete

with all the, sometimes quirky, details, marking all the

churches and even indicating if it has a tower, spire, or

neither. How big is the church is not

shown. The screen is necessarily small so it can be easily held.

A few years ago in Nottinghamshire we were trying to find a

place called Owthorpe but the car's SatNav had never

heard of such a place, which has a population of less than one

hundred people. This was no problem as there it was on the

Ordnance Survey Sat Nav, located with the very extensive index;

this device does not give spoken guidance but a navigator can

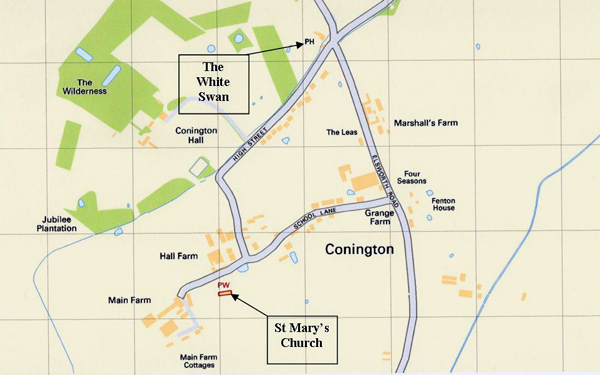

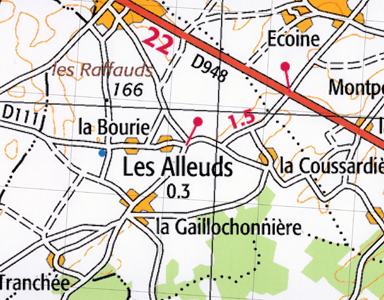

use it with no difficulty.What the standard Sat Nav map does not show are major land marks although I often think this is a feature which would be very helpful, especially in combination with an Ordnance Survey map, even if only for an extra check on position. It does show, if you care to fiddle, establishments such as Woolworths, Debenhams, C & A's and other stores but it does not show churches. Showing stores, as recent experience has shown, is not particularly helpful but showing churches certainly would be. Churches have often been in the same site for hundreds of - and sometimes over a thousand - years. I would not include every church: smaller churches and chapels would not be helpful at all for this purpose. I mean the big churches and especially those which send a tower or steeple high into the sky, and which is often the first thing you spot when you approach a village. Our daughter lives near Ely, a very attractive small city with a very attractive (and expensive to visit) cathedral whose lantern tower may be seen for miles across the flat Fenland. She also lives on the edge of several counties, some of which disappear (but sometimes reappear) or move, not literally, of course, but administratively. This causes problems when you need to find in which county a particular village is situated: what it is in is not the same as what it was in. We planned, when we visited our daughter recently, to take the two grandchildren to a church in Conington and when there for a meal at a pub called The White Swan, which I had found on the internet when searching for Conington. The White Swan received excellent recommendations so I thought this would be a good opportunity to educate the children in both the joys of visiting old churches as well as old pubs on the same day trip. The book had said that Conington was in Peterborough, presumably meaning the Soke of Peterborough rather than the actual city of that name, which I believed used to be in Northamtonshire; however the internet had said it was in Huntingdonshire. All of these aforementioned places are now in Cambridgeshire.  Finding Conington on the car's Sat Nav should have been a simple matter

but this turned out not to be the case as there was not one but two villages

of that name: clearly nobody had ever considered a double n Finding Conington on the car's Sat Nav should have been a simple matter

but this turned out not to be the case as there was not one but two villages

of that name: clearly nobody had ever considered a double n to

distinguish between them. One was Conington, Peterborough and

the other Conington, Cambridgeshire. Again this should have been

easy as it was clearly the Peterborough Conington we

wanted and this was easy enough to find. When we arrived,

however, there was just a number of houses arranged in a large

triangle

and nothing else: no church and no White Swan. to

distinguish between them. One was Conington, Peterborough and

the other Conington, Cambridgeshire. Again this should have been

easy as it was clearly the Peterborough Conington we

wanted and this was easy enough to find. When we arrived,

however, there was just a number of houses arranged in a large

triangle

and nothing else: no church and no White Swan.So we drove to the other Conington, a distance of some twenty miles, and there was a pub and a church even though this was an even smaller village than the earlier Conington. Unfortunately, although the pub was indeed the White Swan, the church was St Mary's rather than All Saints', the church I was looking for. So we planned to retrace our journey to the original Conington and think again. Undaunted we first visited the White Swan, where we enjoyed excellent pub grub, and then walked to the church, which proved to be unlocked and which contained a number of interesting monuments. Conington number one was, unsurprisingly, exactly the same as it had been a few hours earlier with neither pub nor church. I then thought of a brilliant idea, that is the thought was brilliant not my thinking of it or I would have thought of it earlier: look on the Ordnance Survey Sat Nav! And, sure enough, there we were marked in the centre of the village and there was the church a short drive away; we had not seen it, nor could it have been seen, from the village. This church was indeed All Saints', the correct one, but it was locked. However it was in the care of that excellent organization The Churches Conservation Trust and on the door was a notice giving the name and telephone number of the key holder; all churches should - but do not - do this. I telephoned the given number and a lady answered giving her name and address and how to find her house; this was, for once, a simple matter as the map clearly shows. The address was one of those with an A after then number and in this case it referred to the relevant door being at the side of this house while the main door was at the front. I knocked and a woman's voice from within shouted, 'Come in, it's not locked.' I went into a very small hallway with a steep stairway immediately facing me. An old lady with a stick appeared on the landing at the top of the stairs and called down to tell me the key was hanging on a rack with others just behind me and the one I wanted was the big one. She looked as if negotiating the rather steep stairs might have caused her some difficulty so she never came down, which was quite unnecessary anyway. I could hear a man's voice too at one point' so I assumed this must have been an grandparents' flat on the first floor of the family house. The lady asked me to post the key through the letter box when I have visited the church. I thanked her and left. We returned to the church, the key fitted, took quite a large number of photographs, relocked the church and returned the key. We had seen no one else.

These events teach us some lessons on what to do and take on a rural monuments hunt: 1) Never use public transport; there usually isn't any anyway. 2) Always take a 1: 50,000 Ordanance Survey map of the area (no other will do), and, if you can, a Sat Nav with O/S maps. 3) A mobile phone 4) Note book and pencil |

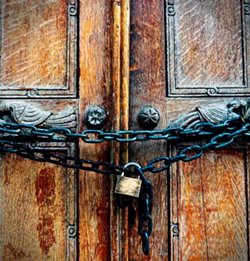

I do not like locked churches, not the churches

themselves, of course, or I would never have tried their doors in the

first place, but rather the act of keeping them locked. In fact, most churches,

both in England and in France, are not locked at all but a few are for

one reason or another. It is not just because I wish to enter to take

photographs that causes this annoyance, as I have usually (although not

always) written to the church in advance, but because many people like

to visit - need to visit - a church to pray, to meditate, to

think, or just for the peace and quiet that we all need at times in

our lives. There is no substitute. They should be open, at least during

daylight hours. We visited one church in Yorkshire some while ago only

to find it locked; I had unfortunately neglected to write to the

church in advance of our visit. There was no notice on the door or

anywhere else giving details of the key holder or the times of opening.

The was a very large sign outside announcing, 'Jesus Welcomes You!'

Had I been one of those minor vandals, armed with and skilled at

using, a spray can, I would have added below, 'But The Vicar Clearly

Does Not!'

I do not like locked churches, not the churches

themselves, of course, or I would never have tried their doors in the

first place, but rather the act of keeping them locked. In fact, most churches,

both in England and in France, are not locked at all but a few are for

one reason or another. It is not just because I wish to enter to take

photographs that causes this annoyance, as I have usually (although not

always) written to the church in advance, but because many people like

to visit - need to visit - a church to pray, to meditate, to

think, or just for the peace and quiet that we all need at times in

our lives. There is no substitute. They should be open, at least during

daylight hours. We visited one church in Yorkshire some while ago only

to find it locked; I had unfortunately neglected to write to the

church in advance of our visit. There was no notice on the door or

anywhere else giving details of the key holder or the times of opening.

The was a very large sign outside announcing, 'Jesus Welcomes You!'

Had I been one of those minor vandals, armed with and skilled at

using, a spray can, I would have added below, 'But The Vicar Clearly

Does Not!'That is another of those unfair statements as it is usually not the vicar at all (or whoever is in charge of the church) who decides whether the church be locked or not but the Parochial Church Council

(PCC).

This is not the same as the secular Parish Council shown in the

illustration, but may function in a similar manner. I came across a good example of this in

Devon where there are four churches strung along a single country road,

one of those mostly single track, tractor infested, winding roads with high banks on

either side, which are common in the South-West peninsular and on which

you travel at your peril. Three of the churches are open but one is

locked. They constitute a joint benefice, being remote churches serving very small

villages with few parishioners. I was lucky enough to meet the vicar, a charming,

friendly lady, in one of these churches and she told me that she would

like them all to be unlocked but the PPC of the locked church insists it be

otherwise. Why? It is often because members of the PCC are sometimes of

a very conservative nature and as the church was always locked in the

past, so always locked it must remain. Curiously this particular church was the

least interesting of the four.

(PCC).

This is not the same as the secular Parish Council shown in the

illustration, but may function in a similar manner. I came across a good example of this in

Devon where there are four churches strung along a single country road,

one of those mostly single track, tractor infested, winding roads with high banks on

either side, which are common in the South-West peninsular and on which

you travel at your peril. Three of the churches are open but one is

locked. They constitute a joint benefice, being remote churches serving very small

villages with few parishioners. I was lucky enough to meet the vicar, a charming,

friendly lady, in one of these churches and she told me that she would

like them all to be unlocked but the PPC of the locked church insists it be

otherwise. Why? It is often because members of the PCC are sometimes of

a very conservative nature and as the church was always locked in the

past, so always locked it must remain. Curiously this particular church was the

least interesting of the four. It is

noteworthy that one of England's largest

ecclesiastical insurance companies advises that generally churches are left

unlocked. This may seem paradoxical but the reasoning is sound: if the

church is locked then the thieves will cause considerably more damage by

breaking and entering than just walking in through the door, and, if they

are up to no good in the church, someone may simply walk in at any time,

as I have often discovered , and catch them in action. Insurance

companies are neither benefactors nor benign so we must assume they know

what they are talking about.

It is

noteworthy that one of England's largest

ecclesiastical insurance companies advises that generally churches are left

unlocked. This may seem paradoxical but the reasoning is sound: if the

church is locked then the thieves will cause considerably more damage by

breaking and entering than just walking in through the door, and, if they

are up to no good in the church, someone may simply walk in at any time,

as I have often discovered , and catch them in action. Insurance

companies are neither benefactors nor benign so we must assume they know

what they are talking about.Even if the church is locked and no permission has been given, there is often a note on the door or at the church yard gate giving the name, address or telephone number of the key holder or occasionally several key holders. So always take a mobile phone, one of the most annoying yet useful devices ever to be invented. It may be, and often is, the house next to the church or somewhere in the village; rarely, if the church is in an isolated position remote from any houses,the key holder may live some distance away - so forget public transport. These key holders are always delightful and helpful people, often quite elderly, and look after the church keys on a purely voluntary basis: they feel the are performing a necessary and helpful duty, which they are, and we should be grateful for such people. Sometimes when you telephone, the key holder will arrive by car (not yet on a motorbike but I look

forward to that day) and open the door for you; they will

ocassionally go away and ask you to telephone them again when you are

finished so they may return and lock the church. On other occassions

they stay in the church, performing various and possibly irrelevant

tasks, to keep an understandable, but still

slighlty irritating, eye on you. Unfortuntely sometimes they follow you

around the church and will not stop talking, sometimes giving you

interesting informtion but at other times not.

forward to that day) and open the door for you; they will

ocassionally go away and ask you to telephone them again when you are

finished so they may return and lock the church. On other occassions

they stay in the church, performing various and possibly irrelevant

tasks, to keep an understandable, but still

slighlty irritating, eye on you. Unfortuntely sometimes they follow you

around the church and will not stop talking, sometimes giving you

interesting informtion but at other times not.If there is no information at the church, you could try the vicarage, but this is becoming more difficult as will be explained in another posting; the pub, yes I did come across one pub which actually was the key holder, otherwise someone in there might know, perhaps even the vicar; or the post office, which themselves are also becoming increasingly rare.

You should always obtain permission to visit the church and take photographs if you possibly can - apart from any other reason - it is only polite to do so - but always stress that it is for academic or research work and not for commercial gain or profit. Although this is becoming increasingly difficult as will be explained in due course.

I always try to write to the person in charge of the church I plan to visit to ask if it is open and if I may take photographs; when I do I usually receive a positive reply. Occasionally, because I forget to write, come upon a church I had not planned to visit, or receive no reply, for reasons which will be referred to in due course, the church is more often than not open. Here are three which were locked. You will note here that in all cases the key holder remained with us during our visit to the church, but this is not always the case.

1. The Peep-Toe Mail

In the North Riding, so the book tells me, there is a church in a village called Whorlton-in-Cleveland and this church contains a well preserved wooden effigy of a knight; I know of no other example in the North Riding, although Alfred Fryer in his book on Wooden Effigies does list several in the West Riding, most of which may be found elsewhere on this site. If you put this village's name into your Sat Nav you may well find t

hat it is 'not

recognized', as the current phrase goes, which clearly sounds more

professional than, although means exactly the same as, 'dunno'! Help is at hand - need I add -

from the Ordnance Survey. There is another Whorlton, which is near

Barnard Castle, both in County Durham; that's not the one,

hat it is 'not

recognized', as the current phrase goes, which clearly sounds more

professional than, although means exactly the same as, 'dunno'! Help is at hand - need I add -

from the Ordnance Survey. There is another Whorlton, which is near

Barnard Castle, both in County Durham; that's not the one, although with boundary changes you would be forgiven for thinking

that perhaps it might be. The book also states that the parish church of

Whorton-in-Cleveland is at Swainby; this confusing statement will become

clearer later. The Ordnance Survey map shows that

Swainby is a medium sized village with a pub and a church (with spire)

and, if you go over the river bridge in that village, you will pass this

church and eventually reach Whorlton, as it is simply called

on the map. This has just a scattering of buildings (probably mostly

farm buildings) and a church

(with tower) as well as a castle. When you do the actual journey you

will find that the church in Swainby, which you will find to be

indeed a medium sized village, is a late

19th century building dedicated to the Holy Cross, but when you pass over

the small bridge and reach

Whorlton there is virtually nothing there except for a ruined castle and

a medieval church , also partly ruined and also dedicated to the Holy

Cross. Apparently what we find is explained by there once being a

medieval village here but which was abandoned long ago; this may have been

owing to the

plague or mass movement for other reasons. There is little or

nothing of this

villageto be seen above the ground now. The area is still called

Worlton-in-Cleveland and its church referred to Whorlton Old Church.

although with boundary changes you would be forgiven for thinking

that perhaps it might be. The book also states that the parish church of

Whorton-in-Cleveland is at Swainby; this confusing statement will become

clearer later. The Ordnance Survey map shows that

Swainby is a medium sized village with a pub and a church (with spire)

and, if you go over the river bridge in that village, you will pass this

church and eventually reach Whorlton, as it is simply called

on the map. This has just a scattering of buildings (probably mostly

farm buildings) and a church

(with tower) as well as a castle. When you do the actual journey you

will find that the church in Swainby, which you will find to be

indeed a medium sized village, is a late

19th century building dedicated to the Holy Cross, but when you pass over

the small bridge and reach

Whorlton there is virtually nothing there except for a ruined castle and

a medieval church , also partly ruined and also dedicated to the Holy

Cross. Apparently what we find is explained by there once being a

medieval village here but which was abandoned long ago; this may have been

owing to the

plague or mass movement for other reasons. There is little or

nothing of this

villageto be seen above the ground now. The area is still called

Worlton-in-Cleveland and its church referred to Whorlton Old Church. You may park outside this church and enter the church yard but, although the church is mainly a ruin, the chancel and the tower have been restored and are in good condition, services being held there at intervals. The churchyard, which contains a number of interesting head stones, may be entered may through its gate but the restored part of the church is locked and there is, at least when we visited, no indication of where to obtain the key. I could not see the wooden knight through either window or keyhole.

However

the internet, that sometimes fickle friend, came to the rescue here:

there is quite a lot of information about the lost village, the

castle as well as Whorlton Old Church, including the e-mail address

of the person

However

the internet, that sometimes fickle friend, came to the rescue here:

there is quite a lot of information about the lost village, the

castle as well as Whorlton Old Church, including the e-mail address

of the person  who

holds the key. I contacted this person and arranged to telephone her

when we next we visited God's Own County. This I did and we arranged

to meet

in the car park of Swainby church and then both drive in tandem to the Old

Church. She was a very friendly and helpful lady who knew a good

deal about the history of the church, even giving us a booklet on

the subject. She pointed out some interesting features both inside

and outside the church, such as the two sided tomb stones with

images of death on the one side and resurrection on the other, which

are here shown to the left and right.

who

holds the key. I contacted this person and arranged to telephone her

when we next we visited God's Own County. This I did and we arranged

to meet

in the car park of Swainby church and then both drive in tandem to the Old

Church. She was a very friendly and helpful lady who knew a good

deal about the history of the church, even giving us a booklet on

the subject. She pointed out some interesting features both inside

and outside the church, such as the two sided tomb stones with

images of death on the one side and resurrection on the other, which

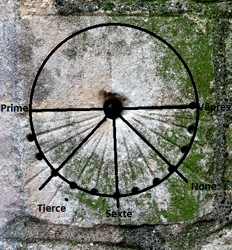

are here shown to the left and right.This knowledgeable lady also pointed out a mass dial on the south outside wall of the church. A photograph of this particular example is shown below on the left. It is said that the six days of the week are represented by the circular row of the lower holes and Sunday is represented by the hole in the centre of the arc of the circle they form. An itinerant priest, if the church had no resident one, would put a light coloured stone in the relevant hole to indicate the day of the week that mass was to be held in the coming week.

There appear to be another variation of mass dials which are sometimes called scratch or tide dials. There are said to be more than 3,000 of these on church walls in England, although some are faintly scratched, and certainly worn, rather than deeply cut as is the example at Whorlton and hence easily missed. A photograph of a rather enhanced one is shown below right.These are in effect vertical sun dials and were always on the outside south wall (the sunny side) of the church near the priest's door. If the are not on this wall, being on another wall or inside the porch, then some rebuilding has occured or a porch added to the church The term scratch is obvious as they appear to have been at times simply and possibly crudely scratched onto the wall; the term tide is derived from tid, an Old English term for a period of time, these dials first appearing in Anglo-Saxon times. Incidentally the use of the word referring to the rise and fall of the sea from the gravitational action of the Moon did not appear until Late Middle English. These dials consist of an incised circle, the lower semi-circle of which has thirteen small holes cut at equal angles around the circumference of this semi-circle and incised radii passing from the large central hole to these holes. Five of these incised radii are more deeply incised. The large central circle held the gnomon (a wonderful word, derived from Greek meaning one who knows) often just a wooden stick, which cast a shadow over the lines. The holes indicated the hours of the day, beginning at 6.00 am and ending at 6.00 pm. The more deeply incised lines represent the times of the Divine Offices, the times of the five daily prayers in a medieval church day. By the 14th century these dials were progressively replaced by mechanical clocks, which initially were erratic in their timekeeping. The plain upper semi-circle represents night time, not an effective time for sun dials!

These dials could not be adjusted for longitude, so would not give the country's 'universal' time but only the local time, although local time is, after all, the real time, as told by the sun. People did not worry too much about this until as late as 1880 when the coming of 'high speed' travel on the railways made it essential to introduce a universal time. Otherwise it would be worse travelling east to west on a USA railway where you have to adjust your watch by an hour when you enter another universal time zone, the east-west width of this country being far too large to have a county wide universal time zone; before the railways and universal time it would meant alteringyour watch each village village visited and by any amount.

|

|

|

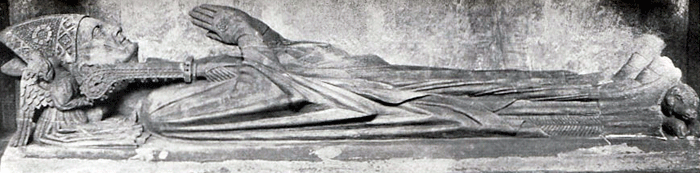

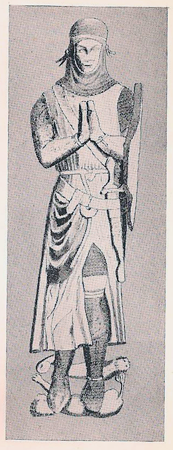

| The wooden knight we see in the photograph above appears to be wearing 'peep-toe' mail stockings, an extremely rare feature, which is mentioned in Fryer's book. There have been various explanations of this curious feature but my own opinion is as follows. The figure is very well carved and appears to have suffered very little damage or vandalism: note the details of the sword belt and spurs. However the mail is not carved at all where, in normal circumstances, it would be exposed, such as on the arms, legs where the surcoat falls back, and the mail hood; it is highly unlikely that the sculptor would have failed to have done this. Effigies of this date were often coated with a thin layer of a plaster like substance called gesso, and fine detail, such as mail, was simple stamped into it, this being a simpler and much quicker process than actually carving all the mail links. The gesso would than be painted. Thus the outline of the mailed toes could still be seen under this coat of gesso. This cost eventually flakes away which explains the state of the effigies today. |

However there are other explanations: one is that the mail was cut short of the toes to make movement more free and the knight would have worn a pair of leather hose beneath, a sort of shoe/sock combination; or that the toes were carved by some skillful vandal. I have no idea what it is like to walk in mail foot wear, allthough the knight in this period would have fought on horseback, but mail shoes are available to buy on the internet if you wish to find out! So I think the open toe idea can be dissmissed.

But there is another effigy of a knight in Pickering, also in the North Riding. This effigy is of Purbeck Marble and the knight wears a later variation of the armour seen here. Purbeck Marble is a hard stone to carve but all the mails links have been carved into the stone where the mail would have been exposed: but his toes are carved , by the looks of it, on one foot only! I think this may be apparent as I could not stand close enough to the effigy to make out the detail more clearly. I know of no other examples with this curious feature. ***

2. The Pretty Girl Holds the Key

Key holders of these locked churches are more often than not middle aged, or even elderly, people who have been trusted to keep the keys safely, only releasing them to those who appear trustworthy, and who often live in a cottage near the church. This proved not to be the case when I visited a church in Somerset a few years ago when I was taking a series of photographs of monuments in that county to add to the Church Monuments Society website; I was Hon. Publicity Officer of the Society at the time and these photographs were to promote the Society's symposium at Bristol, which had been organized by Dr Clive Easter. I had failed to arrange a visit to the church but, in this case, there was a note on the church door stating that the key may be obtained from the house behind the church. I walked round the church to the house but this was no cottage, but rather a large, fine and old manor house. I expected the door to be answered by the maid, but instead there appeared an attractive young woman dressed in what is known as 'hippy' style with long skirt, long free hair and no shoes. She proved very friendly and chipper and walked over to the church with me, still shoeless, to open the church door. She remained with me in the church while I took the photographs, chatting and asking me questions. I often wondered how she managed to walk barefoot on a cold church stone floor.

It wasn't until several years later that I found out who this delightful young lady was or might have been, as this manor house was no longer such but a hotel, or rather one of a number of holiday cottages and manor houses now converted for that very purpose.

3. Private Property - Keep Out

Another locked church we attempted to visit was at Kirkby Fleetham, also in the North Riding. Your Sat Nav will certainly guide you to the village but not to the church which is a short drive away from the former. So it's

Ordnance

Survey to the rescue again, either the 1:50 000 map or the O/S Sat

Nav. In fact you need neither of these as the church is

signposted in the village, although this is easy enough to miss, at least

initially, but I always advise a

Ordnance

Survey to the rescue again, either the 1:50 000 map or the O/S Sat

Nav. In fact you need neither of these as the church is

signposted in the village, although this is easy enough to miss, at least

initially, but I always advise a 1:50 000 map when monument hunting, as churches are not always quite where you think they should be. We soon came to a pull in on the right hand side of the road with two large gates, one signposted 'Home Farm' and the other 'Kirkby Fleetham Hall'; there was also a small sign by the latter gate: 12th Century Church. We drove through the relevant gate, which was open, and along a drive through a wooded area. On either side there were notices fixed to the trees, telling the reader to Keep Out! and that it was Private Property; not an encouraging welcome. We eventually came to a clearing where the church was in front of us. To the right was Kirkby Fleetham Hall, a fine large Grade II* early 18th century house, which has been a private house, a hotel, but was now partly let out as apartments. An occasional person wandered in front of the Hall but no one challenged us. Surprisingly there was not a shot gun or fierce dog in sight. To the left was a car park with the notices: No Parking and Private: Residents Only. Fortunately there was a small area of somewhat informal parking in front of the church. As expected the church was firmly locked. However there was a notice board giving the name and telephone number of the current vicar.

We intended to visit this church on our next visit to the North Riding but had lost the details of the vicar who, it transpired, had moved to another parish anyway, leaving the church in 'interregnum'. The details of the

person to contact was on the

church's website and I e-mailed the person concerned,

who was one of the church wardens. A reply came from a lady and I arranged to telephone her when we had

arrived in the North Riding. It is quite difficult to make these

appointments precisely since it is impossible to accurately plan the

times ahead. I telephoned on a suitable day and we arranged to meet

outside the church. I asked about parking and was told to simply

park on the grass verge outside the church as that was the normal

arrangment.

person to contact was on the

church's website and I e-mailed the person concerned,

who was one of the church wardens. A reply came from a lady and I arranged to telephone her when we had

arrived in the North Riding. It is quite difficult to make these

appointments precisely since it is impossible to accurately plan the

times ahead. I telephoned on a suitable day and we arranged to meet

outside the church. I asked about parking and was told to simply

park on the grass verge outside the church as that was the normal

arrangment. There were the two gates and the notices giving

information but the hostile notices fixed to trees along the drive

had now gone. We parked on the grass as arranged and the key holder lady

arrived shortly afterwards; she was, as ever, a very helpful person and keen

to tell us all she knew of the church. I asked her about the

local situation and

was told that the Hall had recently been sold to another owner, so hence the

welcomed disappearance of those unwelcomed notices, that the forbidden car

park served a number of properties, which we could not see, on the other side of the church

to the Hall, and, as mentioned, that the

vicar had left now the parish. She unlocked the door and I was delighted

to find a number of fine monument sinside, including the

cross legged knight, shown below, who is locally referred to as 'The

Crusader'. Although certainly not a crusader this is a very fine

stone effigy indeed. Note the fine carving of the mail, sword and

sword belt and the heraldry on the shield, which are, as often as

not, quite blank, the heraldry having once been painted but having

since disappeared. Note the toes are not suggested at all.

There were the two gates and the notices giving

information but the hostile notices fixed to trees along the drive

had now gone. We parked on the grass as arranged and the key holder lady

arrived shortly afterwards; she was, as ever, a very helpful person and keen

to tell us all she knew of the church. I asked her about the

local situation and

was told that the Hall had recently been sold to another owner, so hence the

welcomed disappearance of those unwelcomed notices, that the forbidden car

park served a number of properties, which we could not see, on the other side of the church

to the Hall, and, as mentioned, that the

vicar had left now the parish. She unlocked the door and I was delighted

to find a number of fine monument sinside, including the

cross legged knight, shown below, who is locally referred to as 'The

Crusader'. Although certainly not a crusader this is a very fine

stone effigy indeed. Note the fine carving of the mail, sword and

sword belt and the heraldry on the shield, which are, as often as

not, quite blank, the heraldry having once been painted but having

since disappeared. Note the toes are not suggested at all.On the right is the monument to William Lawrence (1785) by Flaxman. On the left side of the pedestal is a pile of books while on the right Anne Sophie mourns beneath the bust of her husband. Below her knees may been seen a pile of coins. I have not been able to discover who this William Lawrence was but his wife was the heiress to the Studley Royal estate, near Ripon

|

In the good old days before the occasional wonders of the internet and e-mails, I would always write to vicars and rectors, enclosing a stamped addressed envelope, to ask permission to visit the church and take photographs. I would nearly always receive a reply giving permission; very occasionally a polite request for me to put a small donation in the box was added.

I cannot recall where or when this occurred but I wrote to one vicar and no reply arrived after waiting several weeks. I visited the church anyway, the door was unlocked and I took the photographs. Then more than a year later a letter arrived with my handwriting on the envelope: it was from this very vicar who apologized profusely, telling me that my letter had become lost under a pile of papers and, of course, I may visit the church and take any photographs I wished, if I had not already done so.

The was no request for a donation but I had put one in the box a year earlier.

And the Post Office

Let us sort out some terminology before we begin.

In England it was always the postman: you may remember it was Postman's Knock, never Postladies' Knock so the poor girls never got a chance. Postman Pat was Patrick not Lady Postman Patricia and the Post Man Always Rang Twice. Although women did carry out this essential work they were certainly in the minority in the past, it always being a postman who delivered the mail to our house. Incidentally in the USA, it's the mailman who delivers the post. So instead of using the long and clumsy phrase, postman or postwoman, let us use the gender free word, postie. The dictionary informs us that this word is Informal English but I was always under the impression that it was Scottish, the Scots being of a more sensible and practical nature.

In France

we have a problem with clumsy phrase reduction. The

majority of deliverers of the mail now appear to be women, all of whom

sport pony tails, although this may well be my personal observation and

not a requirement of employment. In French you cannot, as far as I know, perform this gender freeing of the noun as bizarrely nouns have

their own gender even if the person they refer to is actually of the

opposite gender: an example of this is that the word for mayor is

le maire (masculine) and, even if the maire is a woman she

is still referred to as Madame (feminine) le Maire

(masculine). Rather like saying a lady postman! How a

word can possibly have a gender has never been explained to me. The

postman is le facteur and the postwoman la factrice.

But they will not be here: they are French Posties.

In France

we have a problem with clumsy phrase reduction. The

majority of deliverers of the mail now appear to be women, all of whom

sport pony tails, although this may well be my personal observation and

not a requirement of employment. In French you cannot, as far as I know, perform this gender freeing of the noun as bizarrely nouns have

their own gender even if the person they refer to is actually of the

opposite gender: an example of this is that the word for mayor is

le maire (masculine) and, even if the maire is a woman she

is still referred to as Madame (feminine) le Maire

(masculine). Rather like saying a lady postman! How a

word can possibly have a gender has never been explained to me. The

postman is le facteur and the postwoman la factrice.

But they will not be here: they are French Posties.Returning to England there is a similar situation with the clergy. It was always a clergyman as women were forbidden to become 'of the cloth'. Very foolishly in my opinion, although I do not base this on any ecclesiastical or rational argument, but to the fact that the Queen - a woman - is the Head of the Church of England. What nonsense! But now women can at last be ordained ministers of the Church of England and so all clerical posts are open to them. The non-conformist church became more enlightened long before the C of E. So we shall avoid the long and clumsy term clergyman or clergywoman and instead they are clerics from now on.

So praise to the postie and to those backroomers (gender free) who sort the mail. They manage to bring the post to the right person, even if the writing is virtually illegible and the address a

muddle or even completely wrong. I now normally e-mail a church (if I

can find the e-mail address, which sometimes I cannot) for permission to

photograph but the response is poor: I may only receive replies to