| Visiting the Church and Obtaining

Permission |

The majority of parish churches in Britain as well as in France are open during the day although

the times of opening and closing do vary; however, visiting

between 11.00 am and 4.00 p.m. should find the great majority open.

There is a local French church which has different opening hours

on different days and even that changes with the months; however

that is the exception rather than the rule for churches. I must

add that in contrast this is not the case for French shops whose

opening times are somewhat arbitrary! Some

churches are kept locked: sometimes there appears to be a good

reason for this, other times there does not. For example, there

are a series of churches along the same country road in Devon

which are part of a team benefice; three are kept open but one

is locked. It seems that the team clergy would like to keep all

churches open but the parochial church council of the church in

question prefers to keep it locked. Incidentally, it is the least

interesting church of the series.

At one time it used to be said that the key was

kept somewhere in the porch, on top of a notice board or behind a

seat for example. This may well have been for cleaners, flower

arrangers and others who had regular business in the church. I have only ever

come this once: I had walked several miles to a small country

church in Devon only to find it locked. I tossed my rather heavy

walking stick onto a seat in the porch in frustration and to my

surprise the key fell to the floor; it mush have been secreted

under the seat. This is not advising you to attack the fixtures

and fittings in the porch with stick. On another occasion I wrote to the

vicar of a church in Hampshire asking for permission to visit

the church; this however turned out a

'redundent' church, as they used to be called at the time, but

the post office very efficiently, as always, delivered my letter to the

church's key holder. This person wrote to me and asked me to

telephone him for an appointment. This I did, indicating the day

I would like to visit and this caretaker rather curiously

gave me his address and said that a key would be available under

a large stone on the door step at 10.00 o'clock. I arrived

early, as I always do, looked under the large stone but

found

no key. I rang the door bell but there was no answer. I sat in my car

outside the house but the door did not open and no one arrived.

At 10.00 o'clock I walked up the short drive, lifted the stone

and there was the key.

However you do not have to hunt the key as many

locked church have a notice board at the gate or in the porch

giving the name, address or telephone number of the key holder.

The house is often very near the church so always take a mobile

phone. In every case case I have found the key holders more than

happy to help. Sometimes they go along with you and are always

very pleasant if, at sometimes, rather garrulous. Of course they

are keeping a watch on you but often will give you interesting

information about the church.

If you are planning a special journey to visit

a church it is always advisable to write, telephone or e-mail to the vicar, rector

or whoever is in charge of the church to ask if and when the church is open and if it is not who is

the key holder. It is wise to mention the purpose of your visit.

Always write in good time as with large teams of parishes the

post office may not know where to deliver your letter

immediately. The vicar of a small village may not longer live in

the vicarge and the rector of Microtown may no longer exist.

Always state clearly that your photographs are for personal or

academic use and never for personal gain orcommercial purposes.

If they really are for a commercial purpose do state this as there may,

quite reasonable, be some

financial arrangement involved . The contact

details are now very often on the internet and very often on a

site called A Church Near You. These normally give an

e-mail address of the vicar, rector, priest-in-church or other

contact for the church in question. However the internet is not

always as up to date as we should like it to be and if your

e-mail receives no reply and has not bounced back it may be that

there is no one at the other end because the church is in

interregnum. If you then write to the church you letter may well

be delivered to the right person as the post office and postmen

and women have more initiative and intelligence than the

internet!

Even if you are not planning a special journey

and you know the church is kept open, it is always polite to ask

the church authorities for permission to take photographs

anyway. I have never to date been refused this. Cathedrals and

some large churches, such as Tewkesbury Abbey, have a help desk

where you may ask for permission. For a cathedral you write to

the Dean: he's in charge and will pass on your letter to the

head verger, publicity officer or whoever deals with such

letters. Some cathedrals charge an entry fee, some charge a fee

for photography (and give you a stick on badge!) but these are

not only variable but curious. Sometimes there is an extra

charge for tripods while sometimes they are not allowed at all

during certain times; this is quite reasonable when the large

churches have a large number of visitors. Sometimes flash is

reasonably subject to certain restrictions.

I have once been refused permission in a

cathedral and that

was by Durham but they have now changed their rather unfortunate policy

in this matter. Yes, you could

obtain permission before their recent enlightenment but you had

to ask for this in writing beforehand, the cost

was restrictively high, the time you could spend severely

limited, you were not allowed to include members of staff or

children in your photographs, and you were not allowed to use

either flash or tripod. This is mentioned on the Durham page.

Westminster Abbey does not allow photography (they want to sell

you their own large collection of photographs!) but I probably

could not afford to visit this most expensive church anyway. I

think St Paul's Cathedral does not allow photography but Amanda

did take large number and presumably wrote for and was given permission.

|

Photographing Monuments |

Church Monuments are difficult to photograph:

earthquakes aside the monument is highly unlikely to

move but you might. Because church interior are often on

the dark side you may well need a

long exposure to

allow enough light through the lens into the camera.

The are three way of controlling this:

| 1. Shutter speed |

2. Aperture of the

lens |

3. Film speed - or

on a digital camera, effective film speed |

Shutter speed tells you how long the shutter is open; it

should rather be called shutter time. On the more

professional cameras you can set this at anything from

1/8000 second to 30 seconds or even minutes or hours if

you control this yourself. The longer time the shutter

is open (confusingly a long shutter speed) the more

light enters the camera. Ideal for church interiors?

Yes, but if you hand hold the camera on anything more

than 1/50 sec you will get 'camera shake', unless you

have a steady hand. So the camera will need supporting

on a fixed surface - or you can use a tripod. Both of

these can be limiting, of course. Shutter speed tells you how long the shutter is open; it

should rather be called shutter time. On the more

professional cameras you can set this at anything from

1/8000 second to 30 seconds or even minutes or hours if

you control this yourself. The longer time the shutter

is open (confusingly a long shutter speed) the more

light enters the camera. Ideal for church interiors?

Yes, but if you hand hold the camera on anything more

than 1/50 sec you will get 'camera shake', unless you

have a steady hand. So the camera will need supporting

on a fixed surface - or you can use a tripod. Both of

these can be limiting, of course.

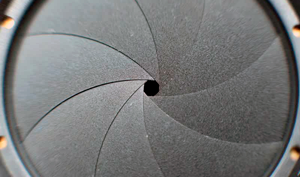

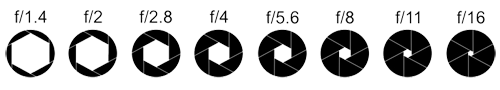

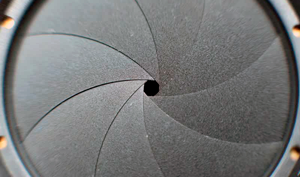

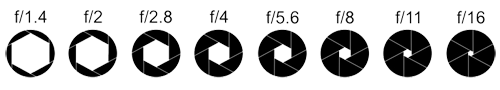

Aperture tells you how wide the lens is open which is

controlled by a clever diaphragm. This is given by

those F numbers but, confusingly, the small the number

the wider the aperture. This is because it's a ratio and

this actually does make sense but I will not go into

that here. The wider aperture the more light enters the

camera. So problem solved for photographing in bad

light: just use a wide aperture? Sorry, no that

won't work either: you didn't really expect it to. The

problem here is that the wider the aperture the smaller

the depth of field. This is if you focus on

something it tells you how far behind and in from of

that something, things will still be in focus. This can

be solved by taking photographs with the subject as flat

as possible. By that I mean do no photograph an effigy

from the feet looking towards the head for if you have

set the focus on the feet, the head will be out of

focus; so take it from the side.

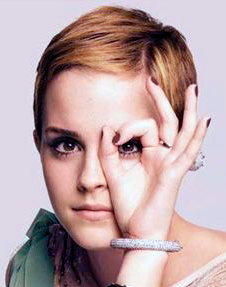

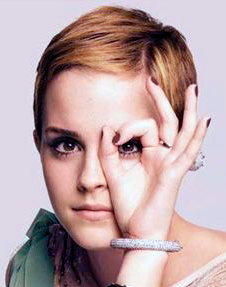

You can see the effect of small apertures like this. If you need reading

glass try looking at text without them: it's blurred,

out of focus. Now make a tiny aperture with

your index finger and thumb and try again: suddenly you

can read it. A good technique if you forget your specs

although you might look rather eccentric. Although

someone

might offer to buy you some spectacles! blurred,

out of focus. Now make a tiny aperture with

your index finger and thumb and try again: suddenly you

can read it. A good technique if you forget your specs

although you might look rather eccentric. Although

someone

might offer to buy you some spectacles!

Film speed. This tells you how fast or slow this

film is, meaning that a fast film will need less light

to expose it correctly than a slow film. So you will be

able to set a shorter exposure on your camera than with

a slow film. Film speed was set by an ASA number: most

films were 80, 200, or 400 ASA, not at all a big range.

You can also 'push' films to a higher rating if you're a

crack hand in the dark room. Will this help? By now you

will expect there will be a trade off: the bigger the

ASA number, the grainier the photograph will look. It

was only the most sophisticated cameras which allowed

you to remove one film and then insert another and then

swap it for the original again.

Help is on its way. On

digital cameras it is possible to adjust to 'speed' or

sensitivity of the film sensor, pushing it up to 25,000

and beyond. A trade off? As you push the speed up the

result becomes 'noisier' but the effect is most quite

acceptable and I regularly push up the speed. For small

images this works very well indeed.

Flash. This would seem to solve all the problems

but not as easily as you might think or hope. First of

all the usual flash on the camera with give a flat,

washed out photograph but there another problem

reminiscent of depth of field, as defined above. Any

light will produce increasingly dimmer and dimmer

illumination with distance; yes, you can see that light

bulb way over there but I will hardly illuminate you

surroundings in the dark. Flash behave in the same way

of course.

The other problem

|

| |

1. My old Agfa camera which

must be half a century old and which cost me £10! The

rings round the lens from the bottom up are:- 1. This

controls the aperture and is set on f8. The controls the

shutter speed, which is set on 1/60 of a second. 3. This

seems to repeat the aperture number and work with

the focusing ring 4. As you turn the ring to the diamond

shaped marker to set the number of feet (yes feet

remember) the lens with focus on, say, 1.6 feet as

in the photograph. If you follow the lines down from the

f numbers they will show you how much in front and

behind the subject will be in focus. Almost nothing ar

f2.8 but better as the aperture gets small toward

f22. The range is small at close focusing range

but improve dramaticall with distance.

Notice how the background is blurred in the photograph as i used a

large aperture and focused close up.

2. Yes like that but smaller...much smaller.

3. 35 mm film cassettes with speeds from 200 to what was then a whopping

1600 ASA.

|

| The Aperture |

|

|

|

| You can just about see the iris diaphragm

through the lens of this (not my) Leica. I had to turn

the camera green to make this possible |

And here's whay it looks like in close up. |

Top: Diagrams of how it works.

Bottom: As ever, nature got there fist and it's

all, unlike the earlier cameras, automatic! |

Do it yourself. At night turn off the lights

and look in a mirror - the iris open and produces

a large pupil; now turn the lights on - and the iris

closes and produces a small pupil.

As you get older the process becomes slower. |

| Saving

& Corruption: A Warning |

|

My great-grandma was quite a feisty girl

|

|

Some years ago I took a large number of

photographs in York Minster and Worcester Cathedral,

uploaded them to my computer then compressed and reduced

them for this site, where they remain. I then saved the

photographs from these two cathedrals and several

other places onto a disc as was

then the procedure. I saved all of the photographs I had

taken elsewhere onto a seies of discs too. When USB keys

arrived, I transferred all the material from these discs

to several keys, the latter being smaller, much more

convenient and, I believe, less prone to problems. All

of the photographs on the discs were accessible except

those from York and Worcester: this particular disc had

become corrupted for no reason that I could ascertain

and all the photographs were lost. This particular disc

was made by Phillips while all of the others were made

by other companies and were fine.

I wrote to Kodak about this problem,

asking them what was the best way to store photographs.

They replied that digital images were actually prone to

failure as my series on the Philip's disc had failed

and, futhermore, technology is advancing so quickly that

stored material that one has today may no longer be

accesible on a device of tomorrow. We have all seen

this, of course: programs that ran on an earlier version

of Windows will not run on a later version. Kodk's advice

was to print the photographs on photographic paper and

store them in the dark at an even temperature. This

sounds sound advice as we can still look at our

Victorian ancestors in photographs taken well over a

century ago. Even a photograph which has faded, stained

and cracked can be restored at least somewhat by an

experienced amateur and even be restored to its original

form by an expert. Whereas my photographs from York and

Worcester are lost and gone forever.

The cynical amongst you will say that

Kodak was trying to sell me lots of their photographic

paper. However they were, as I have shown, quite right

Sound recordings have a similar story:

I like the folk recording made by Moe Ash of Woody

Guthrie, Cisco Houton and others recorded in the mid 1940's

and recently a batch of the metal masters were

discovered which are as clear today as when they were

recorded. How long do casette tapes last and who

invented them I wonder? |

|

Digital photograph of the monument to

Prince William of Hatfied taken in York

Minster a few years ago. |

|

| In Praise of Digital Cameras |

Church monuments are difficult to

photograph and churches are difficult places in which to take

photographs: digital cameras have made life a good

deal easier for the church interior photographer.

A good quality film camera can, in my

experience, takes a far better photograph than an

equivalent digital camera but there are many problems.

Churches are often dark and the monuments often in even

darker corners. If you have loaded your camera with a

400 ASA film, you're in trouble straight away. You can

open your lens to full aperture (causing loss of depth

of field) but the exposure time is still too long to

hand hold the camera so you have to resort to a tripod,

which limits your choices of camera position. You can

change to faster films, if your camera allows it, or

'force' the film on development but this needs

considerable experience - as well as a dark room. Or you

can use flash. A flash, either built in or a separate

flash gun on the camera, gives a flat, washed out look

to the photograph with harsh shadows and if you attempt

to take a photograph with some depths the light from the

flash falls off rapidly with distance giving a very

unsatisfactory appearance. You can use multiple flash of

course but you do need a lot of experience and a lot of

equipment.

Of course with film photography you

will never know what you have recorded on the film until

you have developed it.

The first digital cameras - which

appeared in the 1990's if I remember correctly - were

basic and expensive: I neither wanted not could afford

one. But progress has been amazing. There is no problem

with film speed: my camera will go to an effective film

speed of 25,000; some will go even higher, so you can

take photographs almost in the dark. Quality

deteriorated using these high figures but even this is

getting better. You can see on the camera's screen

exactly how the photographs will turn out so no waiting

in the dark room. You can used multiple flash and see

exactly what the result will be at once. You can hold

the camera at, say, a high angle without looking through

the viewfinder and see on the screen what you have

captured. Some cameras have fold out screens so you can

see what you will capture even before you take the

photograph.

All of this you can attempt with a film

camera but 'blind' camera work is often

disappointing.

Multiple trial photographs of the same subject leads to

using a considerable amount of film, with the additional

cost.

Do not with a digital camera forget to

charge your battery or better still take a spare.

|

|

Drawing |

Pencil drawing is an excellent method for

producing good accurate rendering of church monuments

while in

the church. This is what the etchers such as Charles

Stothard and Thomas Hollis used to do all those years

ago to obtain preliminary drawings for their finished work. I

use a series of pencils from hard to soft with which it

is possible to produce clear lines and good shading.

High lights can be added by using a plastic eraser to

lighten the shaded area. But pencil drawings, no matter

how fine they look, do not reproduce well on the

internet.

Pen and ink drawings are ideal for this

purpose and reproduce very well indeed; the can even be made

to look rather like an etching.

I

executed this drawing of Prince William of Hatfield,

young son of King Edward III by copying an etching by

Charles Stothard. How he produced his original drawing

is a mystery! I

executed this drawing of Prince William of Hatfield,

young son of King Edward III by copying an etching by

Charles Stothard. How he produced his original drawing

is a mystery!

My drawing was executed by using a series of Rotring

pens (which used to be used by architects) on a

special paper called CS10 which was manufactured by Frisk.

The pens have a tubular nib which is best used

perpendicular to the paper and can be used with

Indian Ink. They do give very fine results indeed. The pens are still

available although

very expensive now; they can also

be infuriating: the pens, especially the fine ones used

in the drawing are apt to block from time to time.

Shaking them often unblocks them but there is a danger

of a blot of ink ending up on yours nearly finished

drawing or, perhaps even worse, on the floor. Be careful

not to lose your temper with the pen: violent shaking

can result in the nib hitting the desk and then you

might as well throw the pen in the bin.

Fisk CS10 paper, unlike the confounded yet wonderful pens,

was truly magic. It had a hard surface which sort of

went right through to the back so that you

could

correct a mistake, remove a blot

and, especially

useful, gently scratch the line with a scalpel to make it

less black which made the drawing, as may be seen,

resemble an etching. If you removed an error there would be still a usable

drawing surface below. The surface itself takes a fine

line without it spreading: some papers are almost like drawing

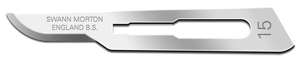

on blotting paper in this respect. I used to scratch out with a number 15

Swann-Morton blade, then use an ink eraser or stick and

finally polish the paper with a pencil eraser. could

correct a mistake, remove a blot

and, especially

useful, gently scratch the line with a scalpel to make it

less black which made the drawing, as may be seen,

resemble an etching. If you removed an error there would be still a usable

drawing surface below. The surface itself takes a fine

line without it spreading: some papers are almost like drawing

on blotting paper in this respect. I used to scratch out with a number 15

Swann-Morton blade, then use an ink eraser or stick and

finally polish the paper with a pencil eraser.

Alas, Frisk ceased production of CS10

paper years ago, so long ago that I have not been able

to fine a photograph of the drawing pad on the internet.

They continued making a board for a few years but that

too is now no longer produced. I do have a few - very

few - sheets left but after that? I have never found a

replacement to CS 10; art dealers have sold me what they

told me was an equivalent but it never was and would not

do what the old magic paper used to do.

|

|

| Swann-Morton

scalpel handle and detachable blade. You can buy

'disposable' all in one scalpels but they don't

feel as robust. With these the handle is

tough and will last for ever; the blades are

carbon-steel and very sharp but will blunt. But

you have to inset and remove the blade so great

care must be taken. I hold the blade in its foil

container to do this and use it as a cover all

the time. Some people use forceps but they just

do not have the control, in my view. |

|

Printing

|

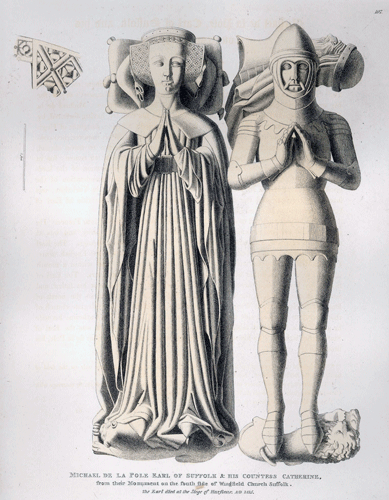

The earliest

illustrations of church monuments were produced by

intaglio printing; these are also the most

beautiful. This, of course, was well before the

invention of photographs and the first stage involved

drawing by pencil the monument in the church, a very

difficult task in itself and I greatly admire the

artists who undertook this skillful work. The image is

then transferred onto a metal plate by creating a number

of lines cut into this plate, the various tones being created by

varying the depth of the line and by cross hatching.

There are other methods and one of these will be briefly

mentioned below. The plate is then inked and passed

though a press producing a print. The plate is then

cleaned and another print made although eventually the

plate will begin to show signs of wear. Different

artists may be involved in the different processes of

this work.

Can you see a problem here? The image on the

plate has to be reversed otherwise the resulting print

will itself be reversed. However there are ways around

this problem, obviously, but I won't describe the

minutia here. Two methods of producing the plate will be

described below

Engraving

In this process the lines are cut into

the metal plate (a steel plate in the example shown) directly by using a tool called a burin.

The depth of the line is controlled simply by

engraving it more deeply. This is very skillful work and

very lengthy, taking days, weeks or months to complete a

plate. Woe betide you should you make a mistake: you

just do not! However the results are truely magnificent:

look at the engraving of King Henry IV and his Queen,

Joan of Navarre on the right. Here the drawing was

executed by architect

Edward Blore which was a major achieving in itself

and if you are familiar with this monument you will,

like I am, baffled by how on earth he managed to do it!

As is sometimes the case the another hand carried out

the engraving: here it was

John Henry Le Keux. I certainly admire the skill of

these Victorian gentlemen.

I have never attempted engraving and, because I

do not have the skill to do so nor the time to develop

that skill nor a master to teach me, certainly never will. I

have tried to use a burin on a cupper plate which was

easy enough but to execute a full detailed plate is

certainly another matter.

The plate then has to be printed and the is dealt

with in etching below. Etching was introduced

because the process is speeder than engraving and this

is now described below.

Etching

The term etching

strictly refers to the process of cutting a line in a

copper plate by a chemical process; the end result, often

called simply etchings, are prints.

The term etching

strictly refers to the process of cutting a line in a

copper plate by a chemical process; the end result, often

called simply etchings, are prints.

In

this process

the copper plate again has lined cut into

it like engraving but the process is very different. The

copper plate is cleaned and covered with a ground,

a waxy like substance that is melted onto the plate

lying on a hot plate. The back of the plate will

probably already be covered in a resistant layer but, if

not, a ground is painted on. The ground is to prevent

the etchant liquid - often nitric acid or a similar

material - from beginning to dissolve the copper.

Then the drawing is transferred to the

plate - remembering to reverse it - so that there is a

fairly simple line drawing on top of the ground.

The ground is then scratched away using an etching

needle, in a series of lines and cross hatching. Unlike

in engraving you cannot make the lines deeper at this

stage. Drawing like this on the plate is called

needling.

When ready the plate is immersed in the

etching agent - usually nitric acid or ferric chloride - for a measured length of times - several minutes

- and then removed. It is then washed and

examined. If you want the lines deeper to give a

stronger line on the forthcoming print the other lines

are stopped out by painting a liquid varnish

over these lines. The plate is then returned to the

etchant bath and again left for several minutes but this

times the etchant will only bite into the lines which

have not been stopped out. This process may be repeated

several times etching deeper and deeper lines. This

process require a good deal of experience to

acquire the necessary skill.

The plate is then removed from the bath,

washed and the ground removed by a solvent. Hopefully we

are now ready to print but the plate could be reground

again and re-etched or the line could be deepened by an

engraving technique or even lessened by careful scraping

and sanding.

Initially the copper plated is

inked: the aim is to cover all of the plate

with ink and especially to force the ink into all of the

etched lines on the plate. Etching ink is very thick and

this

work

is carried out with the copper plate placed on a heated

bed. Black ink is shown here but all colours are

available. You can also produce coloured prints with

different coloured inks but this is beyond the scope of

this short article and certainly well beyond my skill!

This is very messy work! work

is carried out with the copper plate placed on a heated

bed. Black ink is shown here but all colours are

available. You can also produce coloured prints with

different coloured inks but this is beyond the scope of

this short article and certainly well beyond my skill!

This is very messy work!

Next you wipe the ink off

again! Well, not all of it just that which is on the

surface of the plate and not in the etched lines,

obviously. This is a difficult procedure as if any ink

is left on the surface you will end up with a dirty

looking background when you come to produce the first

print: and then you will have to wipe all of the ink off

the plate and start all over again.

Now you are ready to print the plate:

the copper plate in laid on the bed of the etching

press, which is special press rather like an old

fashioned mangle, protecting the bed with clean paper to

avoid any ink marks. This is covered by the dampened

paper, by a protective paper layer and a series of thick

blankets to even the pressure from the rollers You turn the wheel and the

bed with the plate and the paper passes between two

rollers.

|

| |

| The

Artists |

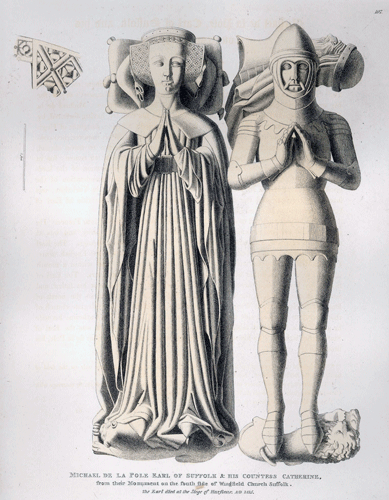

Charles Alfred Stothard

George Hollis (1793-1842) & Thomas Hollis

(1818-43) Father and son who began work on what

was to be a continuation of Charles

Stothard's

Monumental Effigies of Great Britain in 1839,

following the premature death of the latter. George is

described as an engraver and his son, Thomas, as a

painter and draughsman. Initially Thomas executed the

drawings while his father made the etching plates.

George died in 1842 so then Thomas continued the work

alone, executing the original drawings as well as making

the plates. Unfotunately Thomas died of

tuberculosis the

following year at the early age of twenty-five so

the work was never completed.

Their work was published by the same publisher as was

the work of Charles Stothard.

|

|

|

Shutter speed tells you how long the shutter is open; it

should rather be called shutter time. On the more

professional cameras you can set this at anything from

1/8000 second to 30 seconds or even minutes or hours if

you control this yourself. The longer time the shutter

is open (confusingly a long shutter speed) the more

light enters the camera. Ideal for church interiors?

Yes, but if you hand hold the camera on anything more

than 1/50 sec you will get 'camera shake', unless you

have a steady hand. So the camera will need supporting

on a fixed surface - or you can use a tripod. Both of

these can be limiting, of course.

Shutter speed tells you how long the shutter is open; it

should rather be called shutter time. On the more

professional cameras you can set this at anything from

1/8000 second to 30 seconds or even minutes or hours if

you control this yourself. The longer time the shutter

is open (confusingly a long shutter speed) the more

light enters the camera. Ideal for church interiors?

Yes, but if you hand hold the camera on anything more

than 1/50 sec you will get 'camera shake', unless you

have a steady hand. So the camera will need supporting

on a fixed surface - or you can use a tripod. Both of

these can be limiting, of course. blurred,

out of focus. Now make a tiny aperture with

your index finger and thumb and try again: suddenly you

can read it. A good technique if you forget your specs

although you might look rather eccentric. Although

someone

might offer to buy you some spectacles!

blurred,

out of focus. Now make a tiny aperture with

your index finger and thumb and try again: suddenly you

can read it. A good technique if you forget your specs

although you might look rather eccentric. Although

someone

might offer to buy you some spectacles!

I

executed this drawing of Prince William of Hatfield,

young son of King Edward III by copying an etching by

Charles Stothard. How he produced his original drawing

is a mystery!

I

executed this drawing of Prince William of Hatfield,

young son of King Edward III by copying an etching by

Charles Stothard. How he produced his original drawing

is a mystery!

could

correct a mistake, remove a blot

could

correct a mistake, remove a blot

work

is carried out with the copper plate placed on a heated

bed. Black ink is shown here but all colours are

available. You can also produce coloured prints with

different coloured inks but this is beyond the scope of

this short article and certainly well beyond my skill!

This is very messy work!

work

is carried out with the copper plate placed on a heated

bed. Black ink is shown here but all colours are

available. You can also produce coloured prints with

different coloured inks but this is beyond the scope of

this short article and certainly well beyond my skill!

This is very messy work!