|

|

GREATER LONDON |

|

|

|

City of London - 1 |

|

Recorded Burials in the Temple Church References

|

The Temple Church |

|

|

| Underground: Temple:

District &

Circle

Lines There is now an admission charge of £4.00 but with several concessions; photography allowed at no extra charge. 'London's Least Known but Friendliest Church' |

|

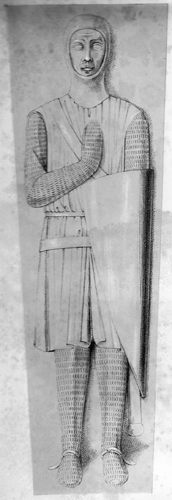

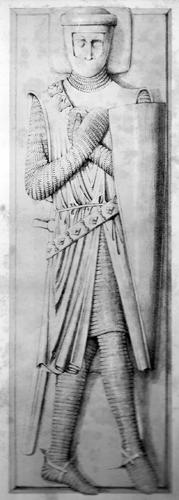

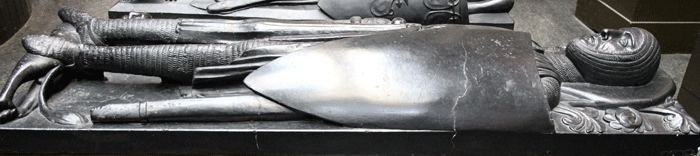

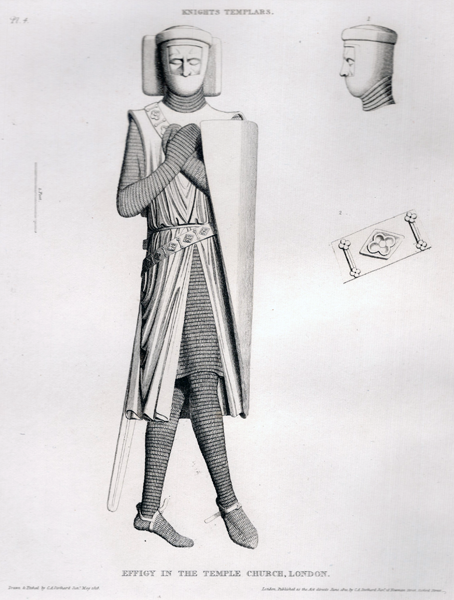

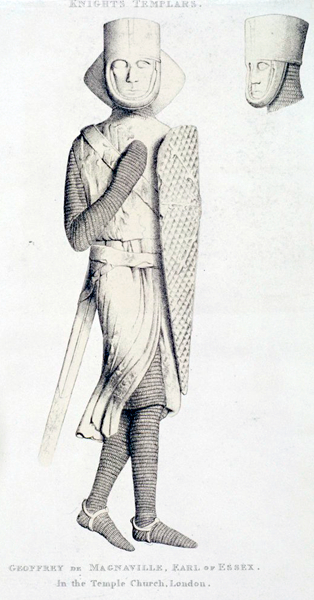

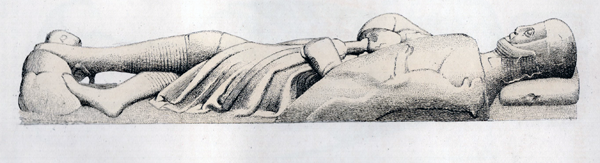

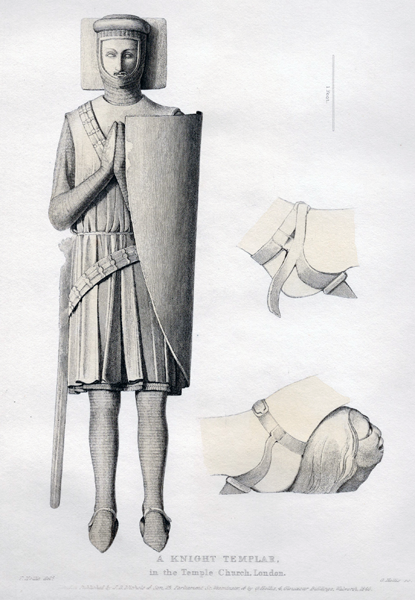

The Temple Church lies between Fleet Street and the Thames Embankment in a complex of buildings of the legal profession. Some of the entrances to this complex may be closed at certain times so it is best to check The Temple Church website for further details and for a useful plan of the area. This website also gives details of the opening hours of the church. The Temple Church belongs to two of the four Inns of Court, the Inner Temple and Middle Temple; it is thus the lawyers' private chapel. It is extra diocesan, has no parish and is not subject to the authority of the Bishop of London, that is, it is one of the few peculiars that still exist in England today. The Temple takes its name from the crusading Order of Knights Templers founded in 1118 to protect pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land. Their names comes from their headquarters being near the site of the Temple in Jerusalem. Henry I introduced them to England and they first settled in Holborn, near the top of Chancery Lane. In the 12th century they built their great house of the New Temple on the banks of the Thames. The Round Church was built on the model of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. The Order was accused of heresy and other offences and dissolved in 1312 at the instigation of King Phillipe Le Bel of France. The Grand Master - Jacques Molay - and others were burned at the stake. In England the Templars' property passed to their rival order, the Knights Hospitallers who, in turn, were suppressed at the Reformation. Thus the Temple eventually passed to the Crown, subject to the tenancies of the lawyers, who had settled there as tenants of the Hospitallers and formed themselves into two societies, The Benchers of the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple, who secured the freehold by charter from James I in 1608. One of the conditions of the grant was that they were to maintain the Temple Church and its services for ever. The Minister of the Temple Church is still called the "Master of the Temple"; his title is 'Reverend and Valiant', reflecting the ancient origin of the church. In the round part of the church, simply called The Round, are the nine military effigies which probably do not represent actual Knights Templers but rather their supporters, some of whom may have actually joined the order shortly before they died while others became 'associate' members. The southern group (on your left) includes the effigy of William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke (1219), who was Regent during the minority of Henry III, and his sons William and Gilbert as well as that of William de Ros, which was brought from Yorkshire, although I have never discovered why. In the southern group (on your right) is the supposed effigy of Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex (1144) and a 13th century coped Purbeck marble coffin lid. The other effigies in both of these groups have not been identified. These monuments were restored by Edward Richardson, whose efforts were much criticized, in the early 1840's; his drawings of the effigies - after his restorations - appear on this page. He also rearranged the position of the effigies to that which we see today; before this they were arranged in line across the Round, being centrally divided onto two groups. It is not known how they were positioned in medieval times. They were also drawn by Charles Stothard, who died in 1821, that is before Richardson's restoration, and the former, a remarkably skillful and accurate draughtsman, produced a series of etchings of the effigies which I will include in this survey; this will give an accurate, albeit two dimensional, representation of the effigies before their restoration. On the night of 10th May 1941 London was subjected to a Luftwaffe bombing raid and the roof of the church fell onto the effigies; they had been protected in the anticipation of such a raid by being surrounded by railway sleepers but this was a fire bomb so each effigy was subjected to its own inferno causing great damage, molten lead from the roof entering cracks in the stonework. The effigies have been carefully repaired by Harold Haysom. Below are photographs of the effigies as well as other monuments in the Temple Church. As can be seen the monuments on the north were more badly damaged than those on the south of the round while those in the nave escaped damage. To see what the monuments used to look like before the bomb damage but, it must be added, after their restoration by Richardson, visit the Cast Courts in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London where Richardson's plaster casts some of these monuments before damage, as well as many others, are on displayed. You may also get some idea from Richardson's drawings on either side of this text or from photographs of the effigies taken before the bomb damage in the RCHM volume, The City. I have added the reference numbers the RCHM gave to the monuments for ease of cross reference. Richardson in his book of The Monumental Effigies of the Temple Church with an Account of their Restoration in the year1842 (London, Oxford and Cambridge 1843) from which the drawings on either side are taken, also gives an account of the various references and drawings of these effigies, in summary thus:

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Plaster Casts of the Military Effigies in the Victoria & Albert Museum |

|

In 1851 the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations opened in Hyde Park in London, housed in the Crystal Place, itself a triumph of Victorian engineering and design, three times the size of St Paul's Cathedral. The Exhibition ran for a little under six months but the Crystal Palace was moved in 1854 to Penge Common. In 1853, more than ten years after his restoration work, Richardson made casts of five of the Temple Church effigies, which were then exhibited together with a very large collection of similar works in the Crystal Palace. Casts of sculpture from all Europe - not just monumental effigies - were so exhibited. The reason for this was to allow people to see these works in three dimensional accurate copies, without the expense, time and difficulty of seeing the originals. We might today would also include add the expense of visiting Westminster Abbey! The Plantagenets from Fontevraud (and elsewhere) joined their descendents from Westminster Abbey (and elsewhere), all together in the Crystal Palace. The ingenious and amazing way these casts were constructed is briefly discussed in the page on the Victoria and Albert Museum. It is very unfortunate (if not rather ironic) that the effigies which received the greatest war time damage were those of which Richardson did not make casts. The Crystal Palace was largely destroyed by fire in 1936 but the casts of the Temple Church effigies together with others which had survived were moved to the Victoria and Albert museum, which profits from the Great Exhibition had been used to found, together with the other large London museums. Below are photographs of plaster casts of the Temple Church military effigies which may be see in the Cast Courts of the Victoria & Albert Museum. These give an idea of what the effigies looked like before the bomb damage. |

|

RCHM-07: Unknown |

RCHM-08: William Marshal II |

RCHM-09: Gilbert Marshal |

RCHM-10: William Marshal |

RCHM-12: William de Ros |

|

| The Effigies Today |

In the 1970's I visited the Temple Church with a film camera and took some photographs of the monuments. There were no railings surrounding them at that time so even with a 28 mm lens I was just able to photograph them from above. I revisited the church around the turn of the century with a digital camera but now railings, albeit very low ones, surrounded the effigies. I again used a 28 mm lens but the camera had a cropped sensor, making the focal length effectively around 35mm, so this, together with the railings, made a bird's eye view impossible to take. There were also a number of electric cables and notices, which I could not help but include in the photographs, as well as difficult lighting. I have attempted to 'photoshop out' the gross obstructions. I did take some close up photographs of interesting parts of the effigies and some side views and these are shown below, together with the scanned photographs from my earlier trip. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

William Marshall (1219) (RCHM no 10 |

Gilbert Marshal (1241) (RCHM no 9) |

William Marshall II (1231) (RCHM no 8) |

Unknown (RCHM no 7) |

William de Ros (1316) (RCHM no 12) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Geoffrey de Mandeville (1144)

(RCHM no 6) |

Unknown (RCHM no 5) |

Unknown (RCHM no 4) |

Unknown (RCHM no 3) |

Richard of Hastings (?)

(c.1185) (RCHM no 11) |

| The coped slab above (RCHM no 11) is of dark marble and has on the east gable a calf's head and on the west a lion's face. Near the middle ridge on either side a batch of foliage |

| Recent Photographs |

|

Unknown (RCHM no 3) |

|

Unknown (RCHM no 4) |

||

Above left & centre top: RCHM No 3. Richardson recorded that this effigy was in 'a fine state of preservation' and had minimal defects. The legs are crossed and the hands are also crossed on the breast, which is exceedingly rare in Britain, although it does occasionally occur in France, e.g. Queen Isabel of Angoulȇme's wooden effigy in Fontevraud Abbey. The eyes appear closed and this feature is again rare, although it occurs in southern but not northern Europe. The coif, or mail hood is not carved at all on the head but apparently seems to finish at the neck.. This is because the coif would have been probably covered by arming cap, in this case a hood (probably of leather) which also covers his mouth and with a padded ring around the temple; the ring's function would have been to help support the great helm (the cylindrical helmet worn over the coif). The effigy is of the mid 13th century of Purbeck marble but whom it represented in unknown Above right & centre bottom: RCHM No 4. Richardson again reports that this effigy had only minor defects. This time the legs are straight and the feet used to be supported by two grotesque but they are hardly discernable now. The mail in this case does not stop at the neck but continues as a mail coif; however he wear a padded ring, as in No 3, and this appears to be surmounted by a skull cap which would have been worn over the mail but under the arming cap. The effigy is of Purbeck marble, of the second quarter of the 13th century but whom it represents is again unknown |

||

|

Unknown (RCHM no 5) |

|

|

|

Richardson comments that the 'state of decay and dilapidations

of this figure far exceeds that of any of the others'. The legs

are straight and have no rests, one arm rests on the breast

while the other holds the low carried shield. The feet, before

the war damage, originally pointed vertically but this is likely

to be a Richardson add-on given the overall low relief of this

effigy. Again there is no mail carving on the head, suggesting

an arming cap which does not this time cover the mouth or show

extra padding. This effigy is of Purbeck marble and in low relief, which, together with the pose (excepting the feet) has led to the belief that this effigy is the earliest: the first half of the 13th century. However the reasoning here is hardly rigorous. Again the represented is not known. |

| Geoffrey de Mandeville (1144) - (RCHM no 6) |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

| A very interesting effigy and it is most regrettable that is has sustained so much damage. The legs were crossed in the manner of those of RCHM no3 although only one now remains. The right hand is laid on the breast while the left arm appears to be holding the shield, on which there can still be seen a carved pattern but there is doubt whether this is a heraldic device or structural reinforcement. | Most curious is the helmet: this is cylindrical with a central reinforcing ridge and a very hefty chin strap. The mail appears to be carved behind the helmet suggesting it is more of a face mask. There also appears to be a strap attached where the helmet meets the chin strap which passes behind the head in order to hold these structures in place. This effigy of Purbeck marble and about 1260. |

|

|

This effigy is said to be that of Geoffrey de Mandeville (1144). He was buried in the Old Temple, of which he may well have been the founder, while still in Templar hands. He was one of the most infamous of the anarchistic barons during the 'anarchy' in the reign of King Stephen. He died while still excommunicated at Mildenhall in Suffolk following a fatal wound; some Templars laid the habit of their order on him and removed his body. He was encased in lead and 'buried' hanging from a tree in the Temple garden; being an excommunicant, for his sack of Ramsey Abbey a year earlier, he was not entitled to Christian burial. His body was transferred to the New Temple twenty years later and buried there following the absolution of excommunication obtained by his son from the Pope in 1163. However there is no existing evidence that this is the effigy of Geoffrey de Mandeville since the Templars (following the Cistercian tradition) did not allow burial inside the church until the end of the 12th century. It would have been therefore more likely that he would have been buried in the porch of the New Temple as a founder. The effigy is, as stated above, dated about 1260, long after his death. It could, of course be retrospective, but this is a mere guess. |

|

Unknown (RCHM no 7) |

|

|

||

| Richardson

writes that parts of this effigy were 'much decayed in places.'

Richardson completely restored the legs which had already been

restored in Caen stone rather than Purbeck marble, although he

stated that the original outline could be traced from fragment

remaining on the base This effigy has crossed legs with one hand resting on the breast

with the other holding his shield, which is larger and held

higher than that of No 5. His head turns slightly to his right. Another effigy of Purbeck marble. This, if it were in its undamaged state, would be a very fine example of the period. Mid 13th century and the represented in again unknown |

|

William Marshall II (1231) (RCHM no 8) |

|

|

||

Richardson reports a number of breakages and that the 'left had excepting the tips of the fingers that remained...the sword hilt from below the left hand were gone.' The hilt could not be missing from below the left hand so he may have meant the right right hand. However earlier drawings indicate that the hilt had survived so he may have meant the quillions (the cross guard of a sword) which certainly were lost; and now lost again after war damage. He copied the scabbard, which was missing, from RCHM No 10 as there were only traces of its original length. The pommel (the knob at the top of the hilt to give the sword balance) is a curious scallop shell, but is not shown thus in the earlier drawing. He writes 'the sword hilt is in the form of a scallop shell'; an explanation is that the original had been covered by the 'crust' which covered the various effigies. Whatever the explanation William II appears to be drawing his sword but his sword hand is certainly in an awkward position. This effigy and the next are of Reigate stone which may explain their better survival from the bombing raid; last quarter of the 13th century. |

||

| In the

First Barons' War he joined the rebellious barons (who

were led by the Dauphin - the future

Louis VIII (Louis the Lion) of France - and claimant

to the English throne) against

King John, while his father (see below) was fighting for the

King. He was one of the twenty-five executors of Magna Carta and

so excommunicated by

Pope

Innocent III , to whom John had finally submitted. He

changed sides and joined his father in fighting for the King;

his excommunication was then lifted. Following the death of King John

(peaches and cider), after which many barons changed sides, he

fought with his father at the

Battle of Lincoln between the forces of the Dauphin and the

new boy king, Henry III. This was the turning point of the War.

He commissioned a biography of his father, the first biography of

a medieval knight. When his father, William I died in 1217, he became 2nd Earl and inherited the post of Earl Marshal. He had no children and his titles passed to his younger brother Richard. |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

| William Marshall was an Anglo-Norman soldier and statesman who served five English kings from Henry II to Henry III. He was a younger son of a minor nobleman, John Marshal, and as such spent his younger years as knight errant (a wandering knight) and a successful tournament competitor. He was knighted while campaigning in Normandy. He had been promised the hand of Isabel de Clare by Henry II and this was confirmed when Richard became king in 1189, so that year the forty-three year old William married the nineteen year old Isabel. Isabel was the daughter of Richard de Clare ('Strongbow'), 2nd Earl of Pembroke and she herself was styled the 4th Countess of Pembroke in her own right. William acquired by this marriage large estates in England, Wales, Ireland and Normandy. He was not officially granted the title of Earl of Pembroke until the second creation of that title by King John in 1199, when he was styled the 1st (Marshal) Earl of Pembroke. His family had held the hereditary title of Marshall to the King, a chief marsall overseeing the other marshall; however, much of these duties were delegated to others who wore more specialised in the work. Because ot this he was known as Earl Marshal. He was one of the few barons who remained loyal to King John who appointed him guardian of his nine year old son, the future Henry III. On John's death he organised the coronation of Henry in Gloucester Catherdral. William led the army that defeated the French forces of the Dauphin Louis (the future Louis the Lion), son of King Philip Augustus of France, who had been invited to England by the rebel barons. Williams's victory at the Battle of Lincoln was the final battle that ended the rebellion and the invasion. William was appointed guardian of the young king and protector of the realm during the minority of Henry III. |

|

Coped Slab (RCHM no 11) See above | |

This is the earliest monument in the church and is of Purbeck Marble, resembling, although more elaborate than, that in Winchester Cathedral which is often said to be of King William Rufus but is more likely that of Bishop Henry de Blois (King Stephen's brother). It has a ridge along all the angles between the raised parts and along the perimeter. Where the three ridges meet on the raised parts, there is in the upper joint a lion's head and at the lower a ram's head. Carved foliage branch off from either side of the long central ridge. This is best seen in the copy of Richardson's drawing which I have reproduced to the left. Although there is no inscription this is said to be the slab of Richard of Hastings, Master of the Temple from 1150's until 1180's, who was responsible for the building of the New Temple in about 1160. The ram's head may represent the Agnus Dei which was the symbol of the Master of the Temple being used on their seals. The protruding horns and tongue give the ram a less than gentle appearance more in fitting for a symbol of the 'Monks of War' |

|

William de Ros (1316) (RCHM no 12) |

This monument is described by David Park (The Temple

Church in London) as 'an effigy without a burial'.

This is an excellent example of an early 14th century

effigy, which fortunately escaped bomb

damage. David Park states that in The New View of London (1708) it is recorded that the effigy was brought here from 'York' by a Mr Serjeant Belwood, who was Recorder of York, in about 1682. The heraldry indicates that it is of a member of the Yorkshire de Ros family. It probably came from Kirkham Priory, near York, from the de Ros mausoleum there, where the only significant burial of the early 14th century was that of William. There is a similar effigy in Bedale, North Riding of Yorkshire. Of Roche Abbey stone and of the early 1300's. Note the bare head with curled hair with the coif thrown back and which rests on a double pillow. The surcoat has loose sleeves reaching to the wrists. The hands are in prayer and the legs are crossed with the feet on a lion. Note the stapes around the wrist. The sword remains in its scabbard, the belt of which is decorated with leopards' heads. The shield is charged with arms: three water bougets, for Ros.

|

||

|

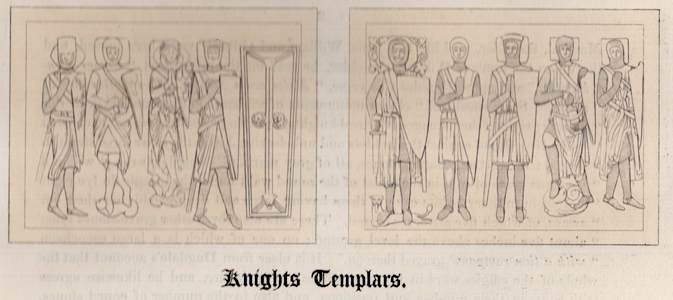

| Published (and Unpublished) Representations of the Effigies |

| As mentioned above in the quotation from Richardson, the first drawings (as far as is known) of the effigies were planned by the Society of Antiquaries, London who commissioned a Signor Grisoni, about whom I can discover nothing, to execute the drawings. Their whereabouts are not known. In 1736 Smart Lethieullier, an English antiquary, informed the Society of Antiquaries that he owned drawings of the effigies which he had commissioned himself, although the artist who executed them is not given. These are presumably those held by the British Library in a collection of drawing which belonged the the Antiquarian. These have never been published but appear in The Temple Church in London. The earliest published illustration were commissioned by Richard Gough and are shown below. These are probably less accurate that the Smart Lethieullier ones mentioned above and certainly not accurate enough for any detailed study. There are watercolours painted by the Rev John Skinner (1772-1828), Vicar of Camerton, Somerset, amateur antiquarian and archeologist during a visit in 1826; he also took brief notes. I have never seen these, either the originals or any reproductions, but am told they again were insufficiently accurate for any detailed study. The drawings of another cleric, Rev Thomas Kerrich (1748-1828), who was Principal Librarian of the University of Cambridge and an artist of remarkable skill, were the first to show useful detail; these are now also in the British Library but unfortunately have never been published. Some of these are obviously preparatory sketches while other are quite remarkable finished drawings, which resemble those of Charles Stothard. Charles A Stothard drew and produced etchings of monumental effigies; to be accurate some drawings were turned into etched by others after his premature death. These are a work of art in themselves and show remarkable accurate detail. He frequently shows the effigy in profile as well as from above and often adds ones or more drawings of details enlarged , which is very helpful. There are four effigies from the Temple Church in this collection T & G Hollis continued but never did complete Stothard's drawings and etching. Their work too is of a high standard and accuracy. The produced two more etching from the Temple Church. These illustrations show, some more accurately than others, how the effigies appeared before their restoration by Edward Richardson. Unfortunately there are just six: the other three were never executed. Edward Richardson published drawings of all of the effigies (including the coped grave cover) in 1843. There are very good drawings and he includes not just the plan view (which I include here) but two elevations of each monuments as well. However these were executed after his restoration so can give no indication of their pre-restoration state. However we can thank the much maligned Richardson for showing their appearance before the bomb damage, not only in drawings but also in making casts of five of them. With the arrival of photography and improved printing technique, the use of the expensive process of engraving and etching as a more or less universal method of illustration came to an end. In my view having taken photographs and made etchings of effigies myself, etchings give by far the most satisfactory result. Actually with the introduction of digital photography and cameras with high effectice ASA numbers, viewing screens, as well as improved ultra-wide angles lenses has made phtography much easier. However one takes hours and the other minutes. The Royal Commission of Historical Monuments produced photographs of all of the effigies (and many of the monuments in the Temple Church their London Vole IV: The City. It has to be commented that some of the photographs are not of the best quality: they were taken in the late 1920's when photography was in its adolescence (not infancy, of course) and had not reached today's standard as well the Temple Church's interior being quite dark because of the Victorian stained glass. However they do give us a good record of what the effigies looked like before the war damage not all that many years later. I should dearly like to know how Thomas Hollis made drawing of the monuments which are built into the structure of Prince Arthur's chantry! An example of why photography will never replace etchings! |

| Richard Gough FSA FRS (1735-1809) |

|

Richard Gough was an antiquarian who was the authour of the massive, five volume work, Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain (1735-1809). The books are profusely illustrated but Gough was not an artist so employed others to carry out the work for the illustrations. These are of variable quality and were critised by no less than Charles Stothard himself for their innacurracies; however Stothard stresses that he is no way criticising the work of Gough himself. I always find the give they monuments an odd, almost doll like appearance. The illustrations are intaglio prints, which were used for early book illustrations, but in this case are engravings rather than etchings. At the base of both is printed Basire Del et Sculp, which refers to the fact that engraver James Basire carried out both the initial drawing and the the engraving of the plates used to make the prints. I think you will probably agree with Stothard in finding these prints of a poor style and probably innaccurate except in general; the engraving inself appears coarse and heavy. These illustrations probably show how the effigies were arranged before their current arrangement which dates only from the restoration of the church. This is mentioned elsewhere |

|

|

||||||||

| RCHM 6 | RCHM 9 | RCHM 12 | RCHM 3 | RCHM 11 | RCHM 10 | RCHM 5 | RCHM 4 | RCHM 8 | RCHM 7 |

| Notes |

Although we probably can learn little from these engravings, they probably show how the effigies were arranged before their current layout: the two prints are probably correspond with the two rows arranged on either side of a walkway. This is confirmed by a similar layout out Stothard drawing below. I must stress that this is not the original medieval layout, which is not known. In general the drawing of the faces is very poorly executed and all the eyes are closed, which they are not. Otherwise apart from fairly small details they do correspond with the Stothard drawings below, more or less. The engraving has produced prints which are heavy and coarse. There are better engravings elsewhere in Gough's work but these are certainly among the poorest. |

| C. A. Stothard |

| Charles Alfred

Stothard was the son of the painter Thomas Stothard and is

described as a 'historical draughtsman'. He began the drawing and

producing etchings of monumental effigies, and this work was

originally published in parts. He was unfortunately killed by a fall from a ladder, which collapsed, while he was drawing a stained glass window in the parish church of Bere Ferrers, Devon. He had stuck his head on an effigy below the ladder. He was buried in the church where his grave stone, now worn to illegibility, may be seen. His work on effigies was never completed but, after his death, some of the drawings were turned into etchings by others and the text of his work again completed by other. The parts were in due course published as a large and hefty volume. His work on this subject is regarded as the finest and the most accurate. His original drawings, not all of which were turned into prints and so remain unpublished, are housed in the British Museum. I will add a page about Charles Stothard in due course. |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| RCHM 12 | RCHM 3 | RCHM 9 | RCHM 6 |

| The Richardson restoration appear to be minor: repair to the shield and sword, replacing the roundel with lions' heads on the belt, adding buckle holes to the belt, giving a hair make over, and perhaps other minor additions and repairs. | The Richardson restorations seems to be minor here | There seems to be more repairs and additions here: the scabbard and part of the sword have been added, spurs have been added, the lion at the feet totally remodeled as well as other minor alterations. This is also shown below | Little work appears to have been carried out by Richardson. Note the singular helmet again: Stothard, whom we can trust to be accurate, had drawn a complete solid structure over the head. There is not sign of mail appearing at the back of the head as it does in the photograph. Was it covered by an early restoration, perhaps. |

| T & G Hollis |

| George and Thomas Hollis were father and

son, both artists and engravers. Their plan was to continue the

work on monumental effigies begun by Charles Stothard after his

accidental, premature death. And this they did, for example in

producing etchings of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia effigies,

which did not appear in Stothard's work. Thomas carried out the

initial drawings and his father, George, the actual etchings.

Their work is similar to that of Charles Stothard and was

published by the same firm but unlike that of the former there

is little text in the published work. Father George died in 1842

while still in middle aged and Thomas then continued the work,

doing both the initial drawingsas well the final etchings.

Unfortunately Thomas himself died (of tuberculosis) the

following year at only twenty-five. The original drawings by Thomas Hollis are, like those of Kerrich and Stothard, housed in the British Museum. The two etchings below of the Temple Church effigies were completed by the father and son. It is interesting to compare the appearance of these effigies before restoration figures with that after restoration; that is, the renderings by T & G Hollis with those of Ricahardson. Did they really need restoring at all? I have copied the Richardson drawings from above so that it is easier to compare the results. . |

|

|

|

|

|

RCHM No 4 Unknown |

RCHM No 10 William Marshal |

||

| Bishop

Sylvester de Everdon (1254) Bishop of Carlisle (RCHM No 1) |

|

This is a very fine mid

thirtieth century

effigy of a bishop which was originally at the east end of the

south choir aisle but was moved to its present position in a

recess in the

south wall of that aisle in the nineteenth century.

Its position meant it escaped the wartime damage which

devastated the other effigies. Note the figure at his feet which is actually a winged dragon and the two small angels on the canopy, one with a censor and the other praying. The effigy is similar to that of Archbishop Walter de Gray (1254) in York Minster. There is actually no firm evidence that this is the monument of Bishop Sylvester, but see below. See below also for information about the body of a child found lying at the Bishop's feet which was discovered when the tomb was opened in 1810 |

|

|

||

|

Bishop Sylvester was an important member of Henry III's

government and at one time keeper of the great seal. He died at

Northampton while on his way to London, following a riding

accident. So it is possible that the entourage would have

continue their journey to London and to the bishops of Carlisle's

house there, which was in the Strand near the Temple

Church. This might well explain why a bishop of Carlisle ended

up in London! There is a mid thirteenth century Purbeck marble of a bishop (possible Sylvester's successor, Robert Vipand, who died in 1256) which may still be seen in Carlisle Cathedral. |

| Post-Medieval Monuments |

|

|

|

|

|

| [RCHM 36] George Wylde (1679) Latin inscription The RCHM reports this to be in the triforium of the round |

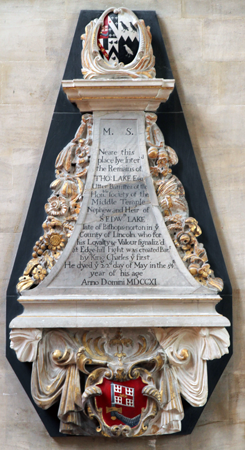

[RCHM 35] Tho[mas] Lake (1711) 'Utter barriſter of the Middle Temple' † The RCHM reports this to be in the triforium of the round |

[RCHM 26] Sir John Williams (1668/9) Latin inscription. By John Stone The RCHM reports this to be in the triforium of the round |

[RCHM 14] Richard Martin (1615) The RCHM reports this to be in the triforium of the round |

[RCHM 13] Sir John Witham Bart (1689) By Thomas Cartwright The RCHM reports this to be in the triforium of the round |

| † An 'utter barrister' is a barrister who pleads without the bar (that is outside the bar, hence utter or outer barrister) and is distinguished from a bencher who is allowed to plead within the bar, as is a Q.C. A 'bencher' is a senior member of an Inn of Court, usually - but not always - a QC, who has been elected to that degree as recognition of contribution to that Inn or to the law. This is now an obsolete term. |

| Other Monuments |

| These monuments are reported in Post-War books but I did not see them. There were monuments visible in the triforium but there was no access |

|

[RCHM 18] Edmund Plowden (1584), Treasurer of the Middle Temple. Altar tomb with alabaster effigy with richly decorated canopy. The RCHM reports this to be in the triforium of the round Edward Littleton (1664), heraldic brass with 29 shields and a Latin inscription of a winding scroll in front of choir stalls. [RCHM 2] John Selden (1654) Middle Temple jurist, legal antiquary and scholar; ledger stone beneath a glass panel. The RCHM reports this to have been in the junction of the chancel and the round; hence the curious numbering. Lord Chancellor Thurloe (1806) bust by Carlo Rossi |

|

Monuments Reported

by the RCHM to be

in the Triforium of the Round See above for any 'missing' monuments in this sequence |

|

[RCHM 15] John Ellys (1686) Oval marble tablet with scrolls, palms, foliage, fruit, and two cherubs' heads, surmounted by two cherub's heads [RCHM 16] Sir Thomas Robinson Bt (1683) Large marble wall monument, middle part with inscription, flanked by Corinthian columns standing on brackets and supporting separate entablatures and a broken curved pediment, enclosing foliage and cartouche of arms; below middle part are a cartouche of arms, festoons and a cherub's head. [RCHM 17] James Howell (1666) Tablet with rectangular inscription slab in frame flanked by Corinthian columns supporting a separate entablatures, each surmounted by a vase; above middle of tablet are a pediment and an achievement of arms. [RCHM 19] Thomas (1671) and William Jollyffe (1680/1) Marble tablet with moulded frame and flanked by composite columns supported on a shelf and trusses; surmounted by a broken scrolled pediment. [RCHM 20] Anne Littleton (1623/4) Inscription tablet large shield of arms; above are a winged skull and hourglass while below scrolled brackets and shield [RCHM 21] Ralph Quarterman (1621) Square inscription tablet, flanked by paneled pilasters with ribband ornaments, supporting an entablature surmounted by a niche contain a skeleton and small panel. [RCHM 22] Thomas Agar (1673) Square tablet in moulded frame [RCHM 23] Sir William Morton (1672) Col. of horse and foot under Charles I. Plain inscribed slab but with mouldings etc on top, probably from another monument [RCHM 24] John Morton (1668), eldest son the above, and Ann, his wife. Originally part of same monument as 23 but now made up of other portions, plain inscribed slab surmounted by two carved panels with trophies of arms with achievements between them. [RCHM 25] Ann Morton (Smith) (1668/9) Wife of Sir William, above. Again originally part of 23, a plain slab, as 23, with pieces of monuments above. [RCHM 27] Thomas Williams (1645) Similar to 26. See above. [RCHM 28] Roger Bishop (1587) Square tablet with scrollwork, foliage frame and shield of arms, above which panel with brass plate with kneeling figures and scroll [RCHM 29] William Freeman erected 1701. Marble with segmental headed inscription tablet in moulded frame; flanked by Ionic columns supporting entablatures and segmented pediment surmounted by a vase and military trophies; outside columns with foliated scrolls and below these moulded shelf with small trusses resting on cherub head and, in middle cartouche of arms. [RCHM 30] William Petyt (1707) Treasurer of the Inner Temple and Keeper of the Records of the Tower. Marble tablet with semi-circular head and moulded edges [RCHM 31] Sir John Vaughan (1674) Chief Justice of Common Pleas. Tablet with inscription panel surrounded by moulded architrave and flanked by Composite columns which support entablatures with broken scrolled pediment enclosing cartouche of arms. [RCHM 32] Edward Turnor (1623) and his second son, Arthur (1651) Inscribed and painted black marble slab with two divisions , each surrounded by a bay tree with one shield above and three below; slab flanked by half Ionic columns and, above the slab, a heavy lintel with broken scrolled pediment enclosing two smaller pediments over each division of the inscription, each surmounted by a wreathed skull and, in the middle, a carved cartouche of arms [RCSM 33] Clement Coke (1629/30) Inscription tablet in moulded frame with clasped hands flanked by two shields above and surmounted by a third shield, and, a curved pediment and achievement of arms; below, two curved brackets and shield of arms. The whole is probably not in its original form but assembled on a modern slab [RCHM 34] Sir Thomas Hanmer (1687/8) White marble, formerly on column and semi-circular in plan. inscription in frame, diminishing towards base and resting on two cherub heads; cornice above continuing beyond on two carved brackets, each with shield of arms; above concave truncated pyramid with achievement of arms, flanked by two seated putti [RCHM 37] John Churchill (1709) White marble cartouche on background of drapery, with trumpets at the side, cherub head below, with shield of arms between. [RCHM 38] Sir Samuel Baldwin (1683) White marble cartouche with drapery; cherub head below, cartouche of arms above. [RCHM 39] Sir John Sympson (1681) Serjeant-at-Law. White marble cartouche with foliage and with cherub head below and cartouche of arms above [RCHM 40] Sir John King KG (1677) Solicitor-general to James, Duke of York. Large marble tablet with inscription in bay leaf, and foliated frame flanked by composite columns resting on a moulded shelf and supporting entablature with broken scrolled pediment enclosing an urn. [RCHM 41] James Sloan (1701) White marble tablet: draped inscription hanging from bunch of flowers with shield of arms in front, two cherubs in front and two below [RCHM 42] Edward Eaton (1687) White marble scrolled tablet with winged skull above and shield of arms below [RCHM 43] William Ceeley (1662) White marble cartouche with drapery, acanthus, foliage and cartouche of arms on top. Erected after 1682 [RCHM 44] Mary Gaudy (1671) and her two brothers, Bassingbourne and William, and her cousin, Framlingham (all 1660-61) Curved marble tablet in moulded frame with fruit and supports at sides; cherub head at base; and scrolls with cartouche at middle. [RCHM 45] Roland Jewkes (1665) Large tablet with inscription in a moulded frame with cherub head atop, flanked by Ionic columns supporting entablature with broken scrolled pediment with flaming urn in middle connected to side of pediment by swags. [RCHM 46] Edward Gybbon (1677) White marble tablet in form of drapery surmounted by achievement of arms. By W. Stanton [RCHM 47] Hutton Byerley (1695) White marble tablet with moulded cornice, broken pediment and shield of arms. [RCHM 48] Henry Wynn (1671) Marble tablet flanked by Composite pilasters surmounted by entablature with broken scrolled pediment, enclosing achievement of arms. [RCHM 49] Sir George Treby (1700) Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. Large white marble tablet with middle part with semi-circular inscription, and two winged cherubs at top and base with trumpets, scales, and foliage. flanking middle part, two twisted columns resting on curved brackets and supporting an entablature and curved pediment with cartouche of arms in middle and tympanum with foliage in low relief. [RCHM 50] John Denne (1648) Painted stone tablet flanked on either side by row of five shields; above cornice and broken pediment enclosing cartouche of arms; below large shield of arms, flanked by carved scrolls. |

| Monuments Reported by the RCHM to be Outside the Church |

Brasses outside the church on south side: 1. Thomas Nash (1648) An inscription plate. 2. Edward Littleton (1664) Inscribed scrolls with shield of arms, with 14 small shields on either side. Indents on north side of church: 1. Of civilian with wife and children, shield, foot and marginal inscription. Late 16th century. 2. On Purbeck marble slab. Coffin lids in churchyard, north of nave: Six tapering stone slabs, five coped. Probably 13the century Floor slabs, originally in church but now in church yard, north of the church: |

| I have, of course, taken the information about the above monuments from the RCHM: London (The City), which I here acknowledge. Many were in the triforium of the round and a few of these were moved into the body of the church following restoration after war damage. I do not know the fate of the others. Nor do I know the fate of those reported outside of the church. |

| Other Recorded Burials in the Temple Church |

1. St Hugh of Lincoln (1200) Entrails only burial in the Old Temple, where he died, although his body was taken to Lincoln. This was after the move of the Templars (in 1161) to the new and present site. At that latter time the Old Temple was a possession of the Bishop of Lincoln and used as his London House. 2. Constant de Hoverio Now lost. Probably refers to a slab with a lost brass indent, recorded in an engraving of 1819. Possibly a Templar of c. 1300 3.William (1256 or 59) Fifth son of Henry III. A skeleton of an infant was found when the tomb of Bishop Sylvester was opened in 1810 and said to be of this William, whose burial in the church in referred to by one of the early writers. 4. Aimery of St Maur (1219) Master of the Temple and successor to Richard of Hastings. His burial is recorded in the History of William Marshall which is mentioned above where it states that he wished to be buried in the nave in front of the rood. There is now no monument to be seen. 5. Robert de Ros (1226/27) This also has been referred to by the early writers above. He appears to have been nicknamed Fursan or Furfan. He joined the Order before he died. 6. Robert de Vieuxpont (1227/28) The two Roberts were northerners, and supporters of King John, although de Ros later became an opponent and was one of the twenty-five barons elected to ensure observance of the Magna Carta. De Vieuxpont was a grandson of one of the assassins of Thomas Becket. These burials were recorded in various documents, although the sites are either given obscurely or not at all. The actual monuments were not described and some of those above may well relate to these burials. |

| References |

|

Richard Gough: Sepulchral Monuments of Great Britain (1735-1809) Charles A. Stothard: The Monumental Effigies of Great Britain (1817-1832) Thomas & George Hollis: The Monumental Effigies of Great Britain (1840-1842) Edward Richardson: The Monumental Effigies of the Temple Church with an Account of their Restoration in the year1842 (1843) RCHM: London. Volume IV: The City (1929) Robin Griffith-Jones and David Park (Eds): The Temple Church in London, (Boydell Press 2010). The monuments are discussed by Philip Lankester and David Park |