Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, know as The Black

Prince

Eldest son of King Edward

III |

|

|

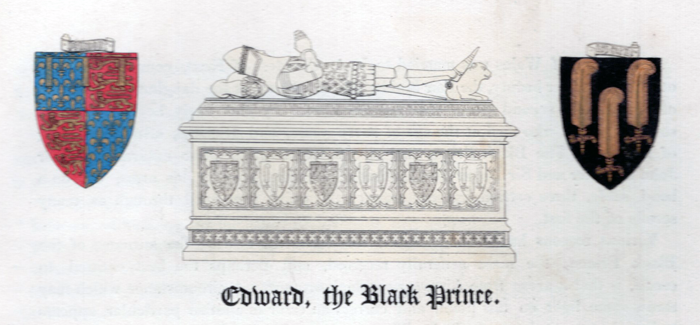

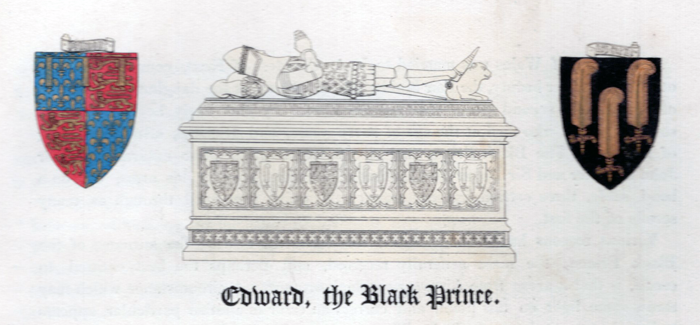

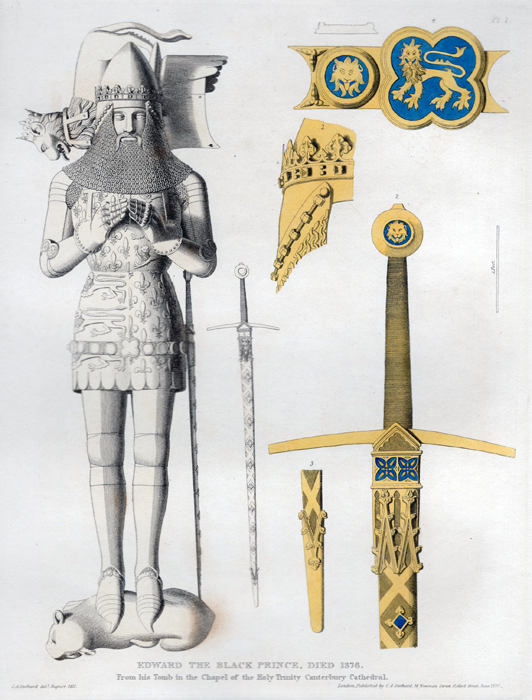

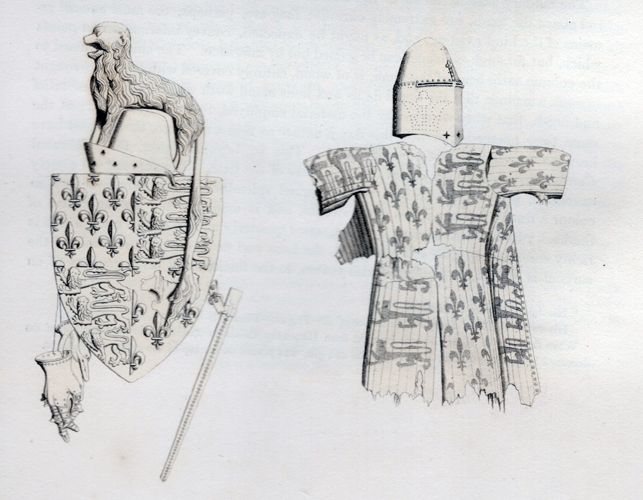

Above and right: Charles

Stothard's drawing and etching of the Black Prince's

monument.

At the very top is a drawing of the gilt bronze

effigy of Edward lying on the tomb chest. To the left is

his arms as the eldest son of King Edward: England

quartered with France with a label indicating the eldest

son. King Edward III, as a grandson of Philippe the

Fair, claimed the throne of France. To the right are his

arms as Prince of Wales.

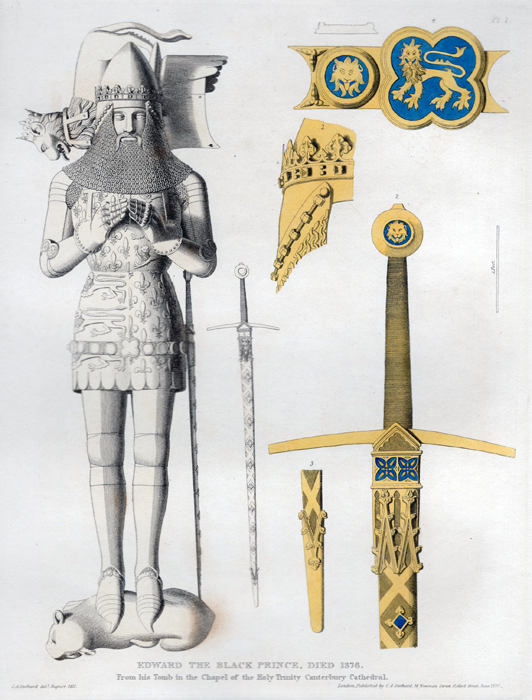

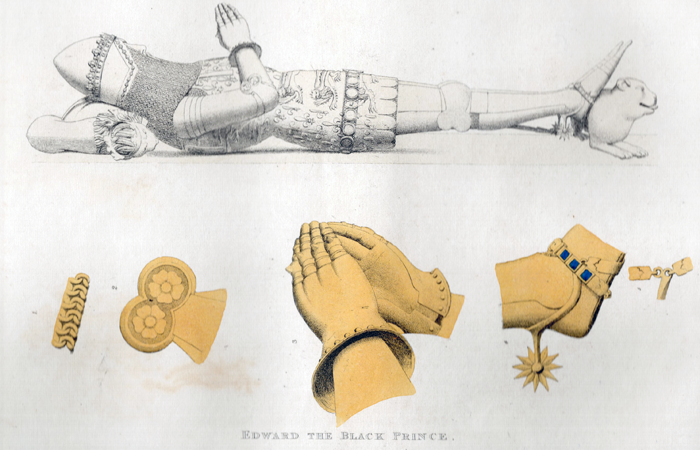

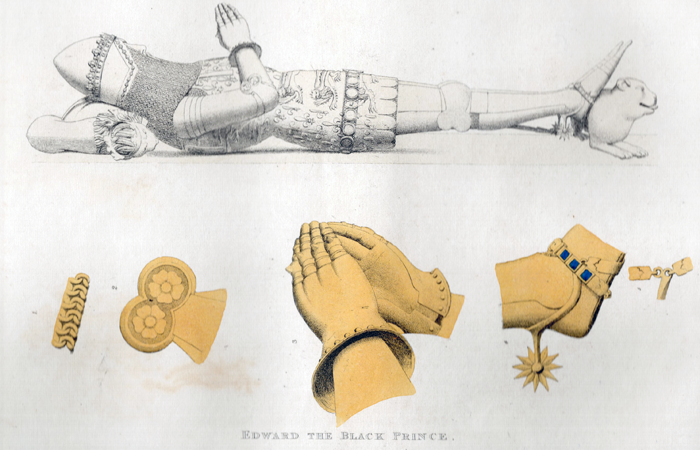

Above: Stothard's etching of the effigy with

various details.

Right bottom: Side view of the effigy.

Right top: Edward's armour which used to hang

over the tomb but is now displayed in a glass cabinet

nearby. Modern replicas now hang over the tomb.

|

|

|

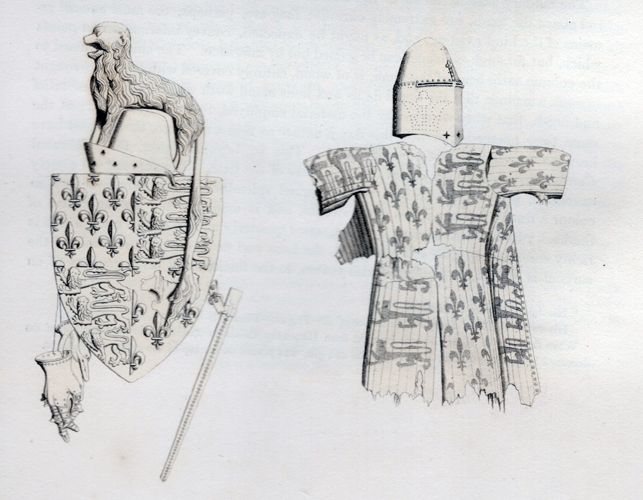

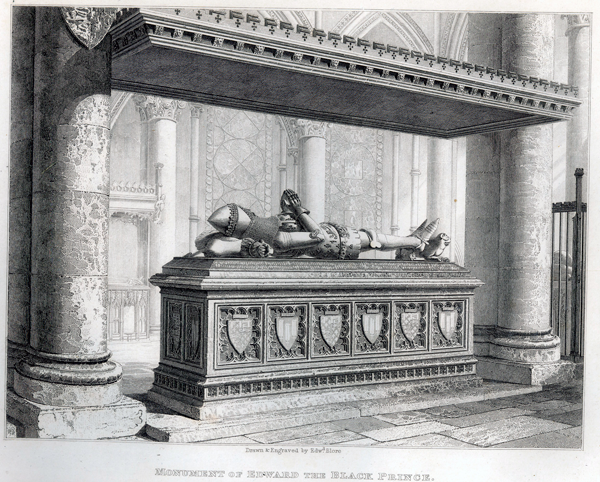

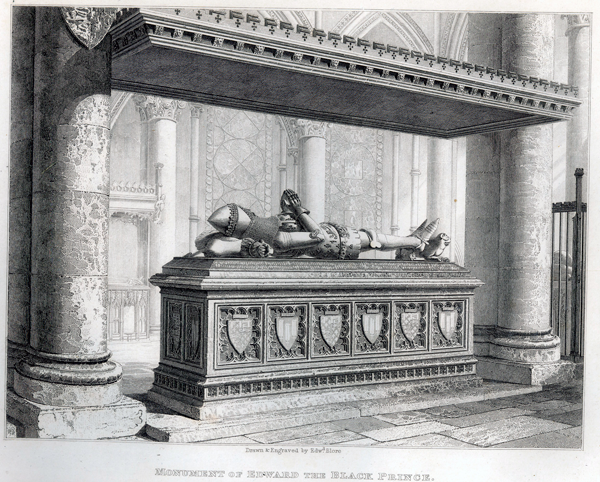

Below and right: : Edward

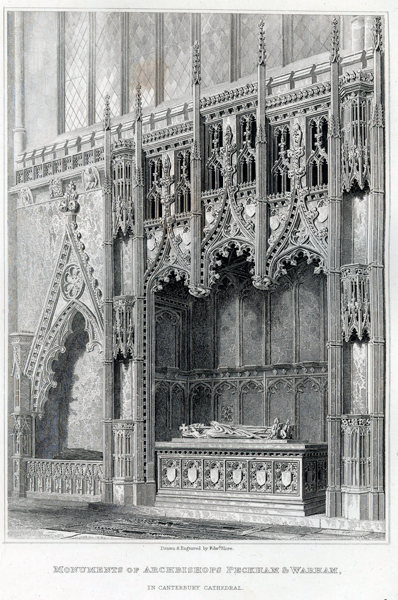

Bore's steel plate engravings of the monument. In

addition we can see the 'tester' hanging over the tomb.

|

|

|

|

The Black Prince |

Edward of Woodstock (1330-1376)

- known as the 'Black Prince' -1 - was the eldest

son of King Edward III and so heir to the English

throne and well as the English possessions in France; he was

also, in name only, heir to the French throne itself. He became

one of the most successful military commanders in the early part

of the Hundred Years' War. Although born to be king, he

was not

destined to be so. was not

destined to be so.

In 1333 he was created Earl of Chester and l137 Duke of

Cornwall, which was the first English Dukedom. Then in1343 he

was created Prince of Wales at the age of thirteen.

the age of thirteen.

In 1346 The Black Prince sailed with his father to

France and took part in the

Battle of Crécy, at the age of sixteen. With other

experienced commanders, including Sir John Chandos, he commanded

the

vanguard,

quite unaided by

King Edward

III, who wished his son to gain military

experience both as a soldier and commander. The English were

victorious and Edward, with his father, marched to

Calais and there took part in the year long siege. Calais was to

remain an English foothold in France for many a year. Father

and son then returned to England.

In 1355 King Edward planned a three pronged attack on France with Prince

Edward, now the King's lieutenant of Gascony,

attacking Aquitaine, although this was no more than a

chevauchée, rather than any major battles being fought. The

Gascons, eager for plunder, were happy to join their English

commander. The following year Prince Edward and his army marched north on

another chevauchée with the intention of linking up, in

Normandy, with his

father and

Charles the Bad, King of

Navarre, at that moment an

ally of the English . However, he was unable to cross

the River Loire so turned west, being flanked by the French army

led by King John

'the Good'. The latter's In 1355 King Edward planned a three pronged attack on France with Prince

Edward, now the King's lieutenant of Gascony,

attacking Aquitaine, although this was no more than a

chevauchée, rather than any major battles being fought. The

Gascons, eager for plunder, were happy to join their English

commander. The following year Prince Edward and his army marched north on

another chevauchée with the intention of linking up, in

Normandy, with his

father and

Charles the Bad, King of

Navarre, at that moment an

ally of the English . However, he was unable to cross

the River Loire so turned west, being flanked by the French army

led by King John

'the Good'. The latter's

father,

Philip

VI, or Philip of Valois, whose confiscation of King Edward's

French possessions had initiated the whole conflict, had by this

time died. The armies were only a few miles apart. There was

also a detachment of French blocking the English retreat. John

of Gaunt, Edward's brother, attempted to come to Prince Edward's aid

but he too was blocked by the French. father,

Philip

VI, or Philip of Valois, whose confiscation of King Edward's

French possessions had initiated the whole conflict, had by this

time died. The armies were only a few miles apart. There was

also a detachment of French blocking the English retreat. John

of Gaunt, Edward's brother, attempted to come to Prince Edward's aid

but he too was blocked by the French.

.png) When

Prince Edward knew that the larger French army now lay between him and

Poitiers

he set up his position on high ground. Edward was in a much

weaker position and was willing to offer very generous terms to

King John. However the French king was persuaded to demand that

Edward and one hundred of his knights surrender themselves as

prisoner and this Edward would not accept. Negotiations took the

whole day which gave the Prince opportunity to consolidate his

position and for the English army to rest. At daybreak of 19th

September the fighting began and this led to an overwhelming

defeat for the French, King John himself being captured by the

Gascon lord

Captal de Buch. On the

following day Edward and his army continued their march - quite

unmolested - towards Bordeaux. A truce was organized and Prince Edward

left for When

Prince Edward knew that the larger French army now lay between him and

Poitiers

he set up his position on high ground. Edward was in a much

weaker position and was willing to offer very generous terms to

King John. However the French king was persuaded to demand that

Edward and one hundred of his knights surrender themselves as

prisoner and this Edward would not accept. Negotiations took the

whole day which gave the Prince opportunity to consolidate his

position and for the English army to rest. At daybreak of 19th

September the fighting began and this led to an overwhelming

defeat for the French, King John himself being captured by the

Gascon lord

Captal de Buch. On the

following day Edward and his army continued their march - quite

unmolested - towards Bordeaux. A truce was organized and Prince Edward

left for England the following year. England the following year.

In 1359 King Edward and Prince Edward sailed together to Calais

where the Prince led a division during the months long

Rheims

Campaign. This was generally unsuccessful and the two Edwards

were happy to abandon the previous

Treaty of London and negotiate

the

Treaty of Brétigny in which the King abandoned his claim to

the French crown in exchange for Aquitaine, Calais and a few

other territories, but no longer under the overlordship of the

French king. This new treaty was ratified by the two Kings

in 1360 as the Treaty of Calais. The French were also quite

happy to sign the treaty as they were in a weakened position with an

outbreak of civil war in northern France and their own peasant

revolt, know as the

Jacquerie. This appeared to mark the end

of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War.

In 1361 Edward, now thirty, married his

cousin Joan,

known 'The Fair Maid of Kent'. They shared the same grandfather

in King Edward I but Joan 's father had been Edmund of

Woodstock, Earl of

Kent from whom she had inherited her title of

Countess of Kent, following the death of her brother. She was

now a widow of thirty-two and had three surviving children by her

previous husband. The following year King Edward granted his son

all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony -

2

as a principality held by

the Prince - now Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony - from his

father. The following year the Prince, Joan and their households

departed for his new principality Although many lords of his

Aquitaine and Gascony came to pay homage to Prince Edward, many

were unhappy about being handed over to an English overlord;

they were also unhappy about the Prince showing favour to his

own countrymen and his Kent from whom she had inherited her title of

Countess of Kent, following the death of her brother. She was

now a widow of thirty-two and had three surviving children by her

previous husband. The following year King Edward granted his son

all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony -

2

as a principality held by

the Prince - now Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony - from his

father. The following year the Prince, Joan and their households

departed for his new principality Although many lords of his

Aquitaine and Gascony came to pay homage to Prince Edward, many

were unhappy about being handed over to an English overlord;

they were also unhappy about the Prince showing favour to his

own countrymen and his ostentatious extravagance, for the Prince enjoyed the outward

show of his status .

ostentatious extravagance, for the Prince enjoyed the outward

show of his status .

Charles V 'The Wise' came to the French throne, following the death

of his father, John, in 1364. No soldier himself, he was

more than happy to encourage and take advantage of this

dissatisfaction of the lords with the Prince, their immediate

overlord. The free companies - bands of discharged soldiers who

became organized under captains - avaged the countryside as

brigands, robbing, and claiming ransoms and protection money.'Free'

because the owed no loyalty to any government but only to

themselves.

It was noted that the companies - who were largely Englishmen or

Gascons - did not attack the Prince's domain, leading to the

belief that Edward, while not actually encouraging them, did

nothing to discourage them either. In this year King Edward asked

his son,

seeing the harm being done to all, to restrain their

activities. seeing the harm being done to all, to restrain their

activities.

In 1365 a group of Free Companies took service with

Bertrand du Guesclin, the famous French military leader, who

used them to drive out the legitimate king of

Castile,

Pedro

the Cruel, and set up his bastard brother,

Henry of Trastámara, in his place. Incidentally Pedro was

also, and rather curiously, known as 'The Just'. Pedro and his

four children, being an ally of King Edward, fled to the Black

Prince at Bordeaux. Pedro persuaded Edward to help him recover

this throne and offered to pay Edward, and anyone who would join

him, by dividing his riches when he

had recovered his throne; he also offered to

pay the wages of the army. Pedro and Edward asked Charles the

Bad for permission to take their army across his territory of

Navarre to Castile. Pedro offered to pay Charles and the Prince

lent him the money; the latter was offered territory as a pledge

and this three daughters as hostages for repayment of the debt.

The Prince had borrowed money from his father and broken up his

plate to help pay his men. When the English and Gascon captains

of the free his riches when he

had recovered his throne; he also offered to

pay the wages of the army. Pedro and Edward asked Charles the

Bad for permission to take their army across his territory of

Navarre to Castile. Pedro offered to pay Charles and the Prince

lent him the money; the latter was offered territory as a pledge

and this three daughters as hostages for repayment of the debt.

The Prince had borrowed money from his father and broken up his

plate to help pay his men. When the English and Gascon captains

of the free

companies

learned that the Black Prince was about to fight for Pedro they withdrew

their support from Henry and joined Edward, whose army consisted

of English and Gascons as well as Bretons and German mercenaries;

there was a civil war in Brittany with the English supporting

the victorious side. The armies met at

Nájera and Henry was defeated and Pedro returned to the

throne. companies

learned that the Black Prince was about to fight for Pedro they withdrew

their support from Henry and joined Edward, whose army consisted

of English and Gascons as well as Bretons and German mercenaries;

there was a civil war in Brittany with the English supporting

the victorious side. The armies met at

Nájera and Henry was defeated and Pedro returned to the

throne.

However this was a pyrrhic victory: Pedro never repaid his debts and

clearly had no intention of doing so as well as refusing to hand over

the promised territories; Pedro soon lost his grip on the throne

and was murdered by his half brother who became know as 'Henry the

Fratricidal'; there was a outbreak of sickness in the

Engish/Gascon army and

many died; the Prince became ill and never fully recovered;

Henry stirred up trouble in Aquitaine; and the French were

angered by the Prince's support for

Pedro against them. John of Gaunt was to marry one of Pedro's

daughters (Constance),

and claim the throne of Castile himself, which was not a wise

decision and would lead to further problems in times to come.

The Battle of

Nájera was to be the final turning

point in the life of Edward, the Black Prince.

Edward on returning encouraged the free companies, who had not been paid

fully, to cross the Loire into French territory to the annoyance

of King Charles who continued to encourage dissatisfaction among

the Gascon lords. The Battle of

Nájera had caused Prince Edward major

financial difficulties: he was unable to fulfill contracts and

introduced a hearth tax which many of his lords refused to

pay. Many such lords took their case to the French

king, who was happy to have this opportunity to request the

Prince's appearance before him in Paris. Edward threw the King's

messenger in jail and replied that yes he would appear but with

an army behind him. By 1367 more than 900 towns and castles had

switched their loyalty to the French King

War was declared in 1369 but although desultory at first it weakened the

English hold on the territory. The following year King Charles

raised two large armies for the invasion of Aquitaine and Edward,

in a period of recovery, responded. The French gained many

important cities and the two French armies met to lay siege to Limoges

which was treacherously handed over to them by the Bishop, a

supposed

friend of the Black Prince. Edward, his temper frayed by his illness,

swore they would pay for their treachery. His health had

deteriorated to the extent that he had to be carried to the operations in a

litter. His sappers brought down a section of the walls and the

city was sacked. The Bishop was brought before Edward who was

persuaded the latter's followers not to have him executed as he had wished. The total loss of life

of the

inhabitants was estimated by recent historians as 300: an order of

magnitude less than that originally estimated. So the Black Prince's

famous black mark turns to a shade of gray. Edward's sickness

worsened so he was no longer able to direct further operations. War was declared in 1369 but although desultory at first it weakened the

English hold on the territory. The following year King Charles

raised two large armies for the invasion of Aquitaine and Edward,

in a period of recovery, responded. The French gained many

important cities and the two French armies met to lay siege to Limoges

which was treacherously handed over to them by the Bishop, a

supposed

friend of the Black Prince. Edward, his temper frayed by his illness,

swore they would pay for their treachery. His health had

deteriorated to the extent that he had to be carried to the operations in a

litter. His sappers brought down a section of the walls and the

city was sacked. The Bishop was brought before Edward who was

persuaded the latter's followers not to have him executed as he had wished. The total loss of life

of the

inhabitants was estimated by recent historians as 300: an order of

magnitude less than that originally estimated. So the Black Prince's

famous black mark turns to a shade of gray. Edward's sickness

worsened so he was no longer able to direct further operations.

The death of his eldest son,

Edward

of Angoulême, who was heir to

the throne, from plague at age five,

greatly distressed the Black Prince and his condition

deteriorated to such an extent his physicians advised him to return home

to England, which

he did leaving his brother, John of Gaunt, in charge of

operations. He retired to his estate at Berkhamstead but by

1372 his health had improved sufficiently for he and his father to sail

to France but contrary winds prevented this and it was not to

be. The wheel of fortune had certainly turned against the Black

Prince who now resigned as Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony.

He took part in some political wrangling in in 1376, opposing John of

Gaunt's anti-clerical party and in the

Good Parliament supported

the commons in thier attack on some of the abuses of the

administration. This latter was not supported by John of Gaunt,

who was to reverse the decisions in the

Bad

Parliament the following year. However later

in 1376

the Black Prince's condition

deteriorated considerably and he died at Westminster. So there

was to be no Edward IV or Edward V in the direct Plantagenet

line.

|

-1 Why

the Black Prince? The simple answer to this is that nobody really

knows. The first reference to the term is by John Leland, the

antiquary, writing 160 years after The Black Prince's death. The are a

few theories:.svg.png)

The first of two is that he wore black armour or carried a black shield. The

first of these can be dismissed at once as the Prince fought in

Southern France and Spain. If you have ever touched a black

metal surface heated by the sun you will see why this is highly

unlikely. A black shield is a possibility as he carried a

'shield of peace' during tournaments and this did indeed have a

black background or field in heraldic terms: sable

three ostrich feathers argent. This can be seen on his tomb

alternating with his shield borne as the eldest son of King

Edward III.

The other explanation is a metaphorical one meaning that he had a black reputation and the

French writers do refer to him as 'black'. He was certainly a

very fierce warrior in a time when such ferocity was valued but

I think this origin is rather unlikely.

- 2

Aquitaine, Gascony or Guyenne, and What

about Poitou? History writers discussing this area of France

seem confused about this aspect of their subject so it is hardly surprising

that their

readers will also become confused in the reading. I often find

that when authors seem woolly they - no matter how well respected

they may be -

simply do not know or understand certain aspects of the suject

under discussion. This judgement is

slightly unfair here at least as there is already confusion in

this situation. Eleanor of Aquitaine (also called Eleanor of

Guyene) brought the duchies of Aquitaine as well as Gascony to

the English crown, and the separate County of Poitou. So

Guyenne seems to be a former name of Aquitaine (it is used by Stothard

in his book) and Poitou is a completely separate entity. Guyenne

is said to be a southern French distortion of Aquitaine,

although in English this doesn't bear any resemblance. The

difference between Aquitaine and Gascony has always seemed to

have been ill defined: sometimes the regions overlap, sometimes

Gascony is part of Aquitaine, while sometimes they are two

separate duchies. Gascony is east and south of Bordeaux and was,

and is, occupied by Gascons (hardly surprisingly) who are said

to have a

Basque origin. The native language of the area - Gascon - is

still spoken there, although it is classified as a variation of

Occitan, the language of southern France. Gascony, in general,

sided with the English during the Hundred Years' War and

many joined

the Free Companies with their English counterparts when the

conditions suited them.

It seems that when King Philip Augustus conquered the (so-called)

Angevin Empire from King John, he removed most of Henry II's

French possessions with the exception of Gascony, or at least

the remnants of the Angevin Empire corresponding to that area.

This was still held by the English king as a fief, with the

French King as overlord, a curious situation. As such, it

appears to have been confiscated by the French king and then

restored at intervals. Edward III originally began the Hundred

Year's War in an attempt to recover this area of France from Philip

VI, before actually claiming the crown himself.

|

|

King

Henry IV

Eldest son of John of

Gaunt, Son of King Edward III.

& Queen Joan of Navarre

His second wife |

|

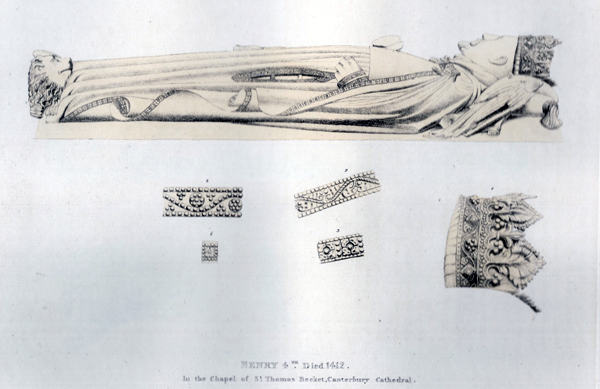

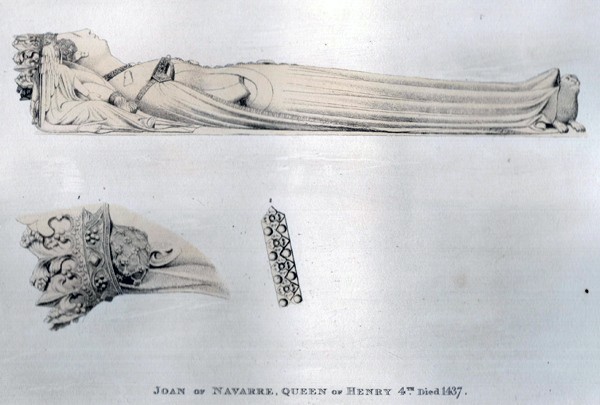

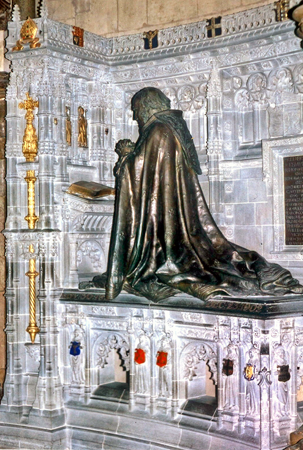

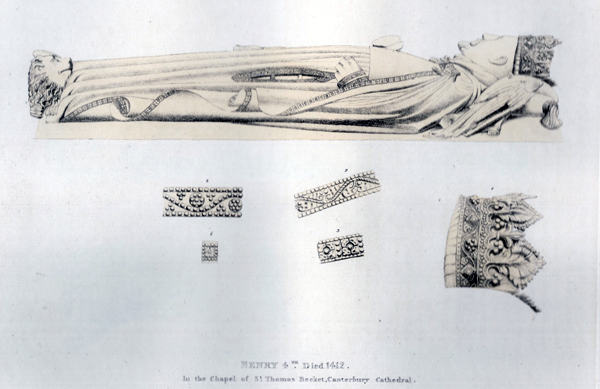

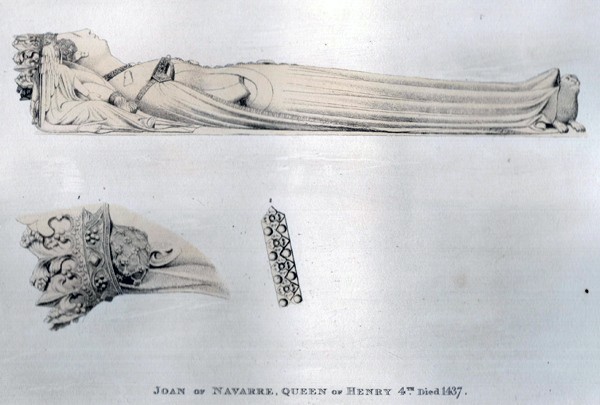

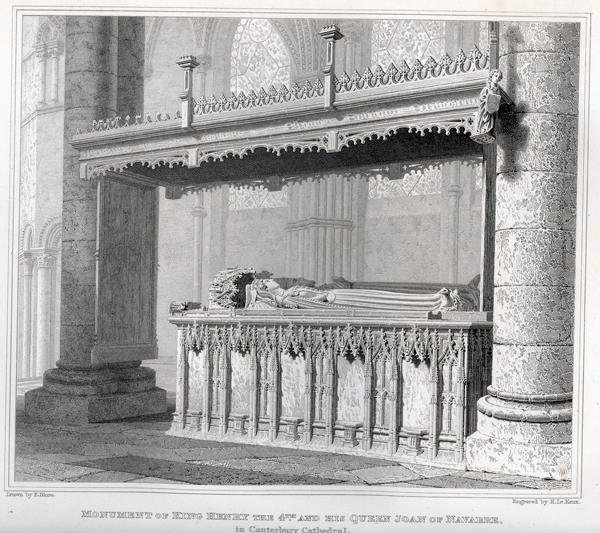

Above and right: The

alabaster effigies of Henry IV and Joan of Navarre, with

details, from the etchings by Charles Stothard.

The effigies are attributed to

Robert Brown 1437

Below:The monument from steel plate engravings by

Edward Blore. On the left we see the effigies again but

with the surrounding structure and the gablettes over

the heads. To the right is the whole monument with tomb

chest, which probably held figures in the niches, and

the tester over the monument. |

|

|

|

| King Henry IV |

Years ago I was in Canterbury Cathedral

looking at the tomb of Henry IV, when a mother and her

child wandered by, the mother telling the child that this was

the king who had six wives. Apart from those monarchs who

had very short or rather obscure reigns, Henry IV must be

England's least known king. This may be because while television, cinema and popular culture tells us

endlessly about the Henry who did have six wives, the

fourth of that name is mostly ignored, so residing in obscurity.

He had two wives, by the way, but neither met such contraversial ends. On

another level the English Monarch Series, books

published initially by Methuen, then later by Yale, began in 1964

but Henry IV had to wait until 2016 to appear, more than

fifty years later. I find this rather curious as Henry IV

had a relatively short reign to study but a very eventful one.

Henry of Bolingbroke, as he was, was not destined to be king: he was

born in Bolingbroke Castle, Lincolnshire in 1367, the eldest son of

John of Gaunt, himself the fourth son of King Edward III, and

his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster. Blanche was the

younger daughter of Henry Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster,

himself the great-grandson of King Henry III, and it is from

Blanche that John of Gaunt inherited his land and titles, her

elder sister having died before her.

Henry was one of the junior Lords Appellant who attempted, and

for a time succeeded, to control the arbitrary and tyrannical government

of King Richard II. John of Gaunt, the King's uncle, helped

Richard slowly regain power when the former returned from his

adventures abroad; Richard set out to punish the Lords Appellant:

the Duke of Gloucester, his uncle, was murdered, the Earl of Arundel

executed and the Earl of Warwick banished. Thomas Mowbray, Duke

of Norfolk, one of the Junior Appellants like Henry, regained

the King's favour and, it is said that on Richard's orders,

organized the murder of the Duke of Gloucester. Henry was left

alone by the King at least initially.

A dispute occurred between Henry and Thomas Mowbray and they

appeared before King Richard. This dispute is obscure, to me

anyway, but it may

have been related to the murder of the Duke of Gloucester. The

King ordered that the dispute be settled by Trial by Battle but

then cancelled this order and banished them both. Thomas Mowbray

died in exile so never returned to England. Henry lived although

while he was in exile his father, John of Gaunt, died

whereupon King Richard, both spitefully and foolishly, seized his

vast

lands, which, of course, were Henry's inheritance.

After consultation with

Thomas Arundel, the former Archbishop of

Canterbury, who had also been exiled by Richard because of his

association with the Lords Appellant, Henry returned to England

landing at Ravenspur in Yorkshire, with Arundel as his adviser.

While Richard was campaigning in Ireland, Henry began a military campaign initially announcing

that he had returned to claim the Lancaster inheritances, but he

gathered enough support to then announce that he was claiming

the crown. Richard returned from Ireland and surrendered at Fint

in North Wales where he was forced to abdicate; he was then was imprisoned in

Pontefract castle. Henry's main supporters on this campaign were

Arundel himself, whom Henry was to reinstate as Archbishop of

Canterbury, and

Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland who was

later

to prove treacherous.

Henry Bolingbroke was crowned as King Henry IV by Thomas Arundel in

Westminster Abbey on 13th October 1399, a year to the day since he had

been sent into exile, and

the line of the Lancastrian Kings began. However it was not to

be a happy reign as will be seen.

Almost immediately in January 1400 there was a rebellion (known as the

Epiphany Rising), by the Earls of

Huntingdon (half brother to Richard),

Kent

(nephew of Huntingdon) and

Salisbury, which

planned to murder Henry as well as the Archbishop of

Canterbury and Henry's four sons

and then return Richard to the throne. Others involved were

Baron Despenser,

Earl of Rutland (Edward of Norwich),

Baron Lumley, and

Sir Bernard Brocas. Also included because he resembled

Richard and could impersonate him was an esquire, Richard

Maudeleyn. They plotted at the home of the Abbot of Westminster

to seize the King at a tournament, kill him and restore Richard

to the Throne. However they were betrayed by one of the

conspirators - the Earl of Rutland - and Henry acted quickly.

The rebels had expected that the whole country would rise in

favour of Richard but the opposite proved to be the case.

Salisbury and Kent were captured by a local authority, tried and

executed; Despenser captured by the crew of a ship he attempted

to flee in and executed as elsewhere and separately were Huntingdon and Lumley. Brocas was

tried in London and executed as was Maudeleyn. The Abbot was

imprisoned in the Tower but soon released. In all twenty-six

were beheaded, six were hanged, drawn and quartered, but many

were pardoned.

There were to be no more attempts to return Richard since he

died in prison in February 1400 shortly after the rising. No one

know how he died: there were said to be no marks of

violence on his remains when examined in the nineteenth century

but this examination neither proves nor disproves a non violent

end. It is said the he may starved himself to death from grief

at the failure of the Epiphany Plot or have been deliberately

staved by his jailors. Whether Henry ordered or had knowledge of

this is unknown and must remain another medieval mystery.

The revolt of

Owain Glyndŵr began in

September the same year and this rebellion was to be prolonged

with many failed attempts at his defeat. He was so successful

that he declared himself Prince of Wales in 1404. The

following year things began to falter, his being defeated by John

Talbot and a month later by Prince Henry. However the rebellion

did not finally collapse until 1409.

During the nine years of the Glyndŵr revolt the rebellion of Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland,

occurred in 1403, ending with the

Battle of

Shrewsbury where both Henry and his eldest son

(the future Henry V) fought the rebels. The younger Henry was

badly wounded and the Earl's son, another Henry, but

conveniently known as Hotspur, was killed. Why this treachery

by the Earl? The Perceys had

fought against the invading Scots at the

Battle of Homildon Hill, where the Scots were thoroughly routed

and many noble prisoners were taken. However, King Henry would not allow

them to be ransomed as he did not wish them to lead another army

into England. This did not please the Earl as ransoming

prisoners was a good source of income, so the Earl decided to

challenge Henry, supporting the Glyndŵr rebellion and linking up

with

Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March. This Edmund Mortimer was

son of Roger Mortimer, the 4th Earl, and thus descended - albeit

via the female line - from an older son of King Edward III

(Lionel, Duke of Clarence) than John of Gaunt; Roger

Mortimer had been vaguely recognized as heir to the throne by

the childless Richard II, ignoring the usual rules of succession

which had been laid down by Edward III. When we include Edmund's

sister into all of this it becomes wonderfully complicated but

that's another story and not relevant here. King Henry did not

charge the Earl with treason as the latter did not personally

take part in the rebellion.

In 1405, again during the Glyndŵr rebellion, there was yet

another Percy rebellion. This was led

by

Thomas Mowbray, 4th Earl of Norfolk (the son of another

Thomas, 3rd Earl and 4th Duke, who had been banished with Henry)

and

Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York. The rebels were

abandoned by the Earl of Northumberland and overcome by the

King's army led by his son, John of Lancaster, and The Earl of

Westmoreland, at Shipton Moor. The judge refused to pass sentence on the leaders

of the rebellion unless they were tried by their peers, so

Henry, probably weary of these rebellions, had them summarily

executed. The Earl fled to Scotland.

When the Glyndŵr rebellion still in progress, in 1408, Earl Henry

Percy invaded England from his exile in Scotland with an army of

Lowland Scots to be met with an army of Yorkshire levies led by

High Sherriff

Sir

Thomas Rokeby at

Battle of Branham Moor. Again the rebel army was scattered

and many killed including the troublesome Earl. The power of the

Perceys in the north was broken, at least

temporarily.

Henry was affected by bouts of incapacitating illness in the last

years of his reign and from 1406 did not act as an effective ruler.

It is difficult to diagnose illnesses from centuries ago and by

the descriptions given by physicians of the time. It was said to

be leprosy sent as a punishment for his usurping the throne,

possible regicide and his execution of Archbishop Scrope. The

symptoms sound like he possibly suffered from

arthritic psoriasis, an auto-immune disease which

includes skin lesions and difficulty with and pain in the

joints, and which becomes increasingly disabling as it

progresses; there are also remissions and exacerbations. There

may well also be a inherited factor.

He died in 1410 at the age of forty-seven.

He married as his first wife

Mary Bohun,

joint heiress with her sister of the substantial estates o f

Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford. She was the mother of Henry V as well as three other

sons and two daughters. Unfortunately Mary died at

twenty-six giving birth to her last daughter, Phillippa, and did

not live to see her eldest son become king.

Henry's second wife was

Joanne of Navarre, daughter of King Charles

the Bad, who had changed sides several times during the Hundred

Years' War under Edward III. Her first husband was

John IV, Duke of Brittany by whom she had four sons and five

daughters. She and Henry had met while Henry was in exile and

they married in 1403 after Henry had became king. She bore Henry IV no children

but may have given birth to two still born babies.

Henry V had a good relationship with his stepmother and she even

acted as regent during his absence in France. However when Henry

V brought back as a prisoner her son, Arthur of Brittany, the

relationship broke down and Joanne was accused of trying to

kill the King by, it appears, witchcraft. She was never tried

but imprisoned in

1419 and all her lands and possessions confiscated. However her

stepson released her and restored the confiscations before he died in

1422

|

| |

|

|

The South Ambulatory |

|

Archbishop Hubert Walter |

Hubert

Walter (c. 1160-1205) was a cleric and

administrator under kings

Henry II,

Richard I and

John. Although neither a holy nor learned man he

became one of the most outstanding government

administrators of the middle ages. Hubert

Walter (c. 1160-1205) was a cleric and

administrator under kings

Henry II,

Richard I and

John. Although neither a holy nor learned man he

became one of the most outstanding government

administrators of the middle ages.

He was aided in this career by his uncle,

Ranulf Glanvill, who was

chief

justiciar under Henry II.

During the reign of Henry II Hubert was appointed Dean

of York, having been an unsuccessful candidate for the

post of Archbishop. He was then was appointed Bishop of Salisbury after Richard became king

in 1189

and then accompanied Richard on the

Third Crusade, departing before the King from

Marseille together with

Baldwin of Forde (Archbishop of Canterbury) and

Ranulf Glanvill, both of whom were to die during

the Siege of Acre. He acted as a principal negotiator with

Saladin

even persuading the latter to allow a few Western

clerics to remain in Jerusalem to hold Christian

services..

Hubert learned in Sicily on his way home from the Holy Land that King

Richard had been captured on his way home and was held

by the Holy Roman Emperor,

Henry VI. He was one of the first to find the

King and was one of those involved in raising the ransom

demanded by the Emperor. As a reward for

these services King Richard wrote to

Queen Eleanor asking her to arrange Hubert's

appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury, the last

incumbent (Baldwin) having died, as mentioned above, in

the Holy Land. He was also appointed chief justiciar; in

this position he effected a number of important legal

reforms some of which are the basis of the English legal

system today, such as the appointment of Justices of the

Peace. He resigned his secular posts in 1198.

He had, not without difficulty, forced Prince John to

submit after he rebelled against his imprisoned brother

Richard using both secular (a siege) and ecclesiastical

powers (excommunication) to effect John's submission.

After the sudden death of King Richard, Hubert supported

John succession against the rival candidate for

the crown,

Arthur I, Duke of Brittany who was the son of

Richard and John's long dead elder brother,

Geoffrey. John's claim was successful and he was

crowned by Hubert in Westminster Abbey in 1199. As a

reward for his services the king appointed Hubert

Chancellor of England, a senior administrative

secular post. Hubert was also employed by John on a

number of diplomatic missions.

Hubert died in 1205 after a long illness.

|

| Above:

Archbishop Hubert Walter (1205).

Purbeck Marble |

|

|

.gif)

was not

destined to be so.

was not

destined to be so. the age of thirteen.

the age of thirteen. In 1355 King Edward planned a three pronged attack on France with Prince

Edward, now the King's lieutenant of Gascony,

attacking Aquitaine, although this was no more than a

In 1355 King Edward planned a three pronged attack on France with Prince

Edward, now the King's lieutenant of Gascony,

attacking Aquitaine, although this was no more than a

father,

father,

.png) When

Prince Edward knew that the larger French army now lay between him and

When

Prince Edward knew that the larger French army now lay between him and

England the following year.

England the following year.

Kent from whom she had inherited her title of

Countess of Kent, following the death of her brother. She was

now a widow of thirty-two and had three surviving children by her

previous husband. The following year King Edward granted his son

all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony -

Kent from whom she had inherited her title of

Countess of Kent, following the death of her brother. She was

now a widow of thirty-two and had three surviving children by her

previous husband. The following year King Edward granted his son

all his dominions in Aquitaine and Gascony - ostentatious extravagance, for the Prince enjoyed the outward

show of his status .

ostentatious extravagance, for the Prince enjoyed the outward

show of his status . seeing the harm being done to all, to restrain their

activities.

seeing the harm being done to all, to restrain their

activities. his riches when he

had recovered his throne; he also offered to

pay the wages of the army. Pedro and Edward asked Charles the

Bad for permission to take their army across his territory of

Navarre to Castile. Pedro offered to pay Charles and the Prince

lent him the money; the latter was offered territory as a pledge

and this three daughters as hostages for repayment of the debt.

The Prince had borrowed money from his father and broken up his

plate to help pay his men. When the English and Gascon captains

of the free

his riches when he

had recovered his throne; he also offered to

pay the wages of the army. Pedro and Edward asked Charles the

Bad for permission to take their army across his territory of

Navarre to Castile. Pedro offered to pay Charles and the Prince

lent him the money; the latter was offered territory as a pledge

and this three daughters as hostages for repayment of the debt.

The Prince had borrowed money from his father and broken up his

plate to help pay his men. When the English and Gascon captains

of the free

companies

learned that the Black Prince was about to fight for Pedro they withdrew

their support from Henry and joined Edward, whose army consisted

of English and Gascons as well as Bretons and German mercenaries;

there was a civil war in Brittany with the English supporting

the victorious side. The armies met at

companies

learned that the Black Prince was about to fight for Pedro they withdrew

their support from Henry and joined Edward, whose army consisted

of English and Gascons as well as Bretons and German mercenaries;

there was a civil war in Brittany with the English supporting

the victorious side. The armies met at

War was declared in 1369 but although desultory at first it weakened the

English hold on the territory. The following year King Charles

raised two large armies for the invasion of Aquitaine and Edward,

in a period of recovery, responded. The French gained many

important cities and the two French armies met to lay siege to Limoges

which was treacherously handed over to them by the Bishop, a

supposed

friend of the Black Prince. Edward, his temper frayed by his illness,

swore they would pay for their treachery. His health had

deteriorated to the extent that he had to be carried to the operations in a

litter. His sappers brought down a section of the walls and the

city was sacked. The Bishop was brought before Edward who was

persuaded the latter's followers not to have him executed as he had wished. The total loss of life

of the

inhabitants was estimated by recent historians as 300: an order of

magnitude less than that originally estimated. So the Black Prince's

famous black mark turns to a shade of gray. Edward's sickness

worsened so he was no longer able to direct further operations.

War was declared in 1369 but although desultory at first it weakened the

English hold on the territory. The following year King Charles

raised two large armies for the invasion of Aquitaine and Edward,

in a period of recovery, responded. The French gained many

important cities and the two French armies met to lay siege to Limoges

which was treacherously handed over to them by the Bishop, a

supposed

friend of the Black Prince. Edward, his temper frayed by his illness,

swore they would pay for their treachery. His health had

deteriorated to the extent that he had to be carried to the operations in a

litter. His sappers brought down a section of the walls and the

city was sacked. The Bishop was brought before Edward who was

persuaded the latter's followers not to have him executed as he had wished. The total loss of life

of the

inhabitants was estimated by recent historians as 300: an order of

magnitude less than that originally estimated. So the Black Prince's

famous black mark turns to a shade of gray. Edward's sickness

worsened so he was no longer able to direct further operations..svg.png)

.png)