| Brittany | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Some Notes on Brittany |

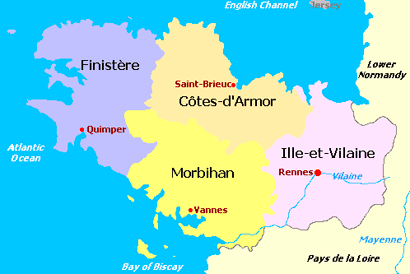

There had been two earlier attempts to rationalize the départements of France, which dated back to the Revolution. The historic and geographical Brittany lost 20% of its area in the Vichy Programme of 1941; these initial attempts were either ineffective or were abolished in 1945. When the regions of France were created in 1956 that 20% - the Département of Loire-Atlantique - was included in the region of Pays-de-la-Loire so that Brittany not only lost one of its five départements but also its regional capital, Nantes, which this département had contained. Many Bretons, understandably, are not at all happy about this as Brittany was quite independent from France for a long period of its history. It is also culturally and linguistically distinct, even though there had been attempts to eliminate the Breton language. The four départments are now: Finistère (capital Quimper), Côtes d'Armor (originally, Côtes-de-Nord) (capital Saint-Brieuc), Morbihan (capital Vannes), and Ille-et-Vilaine (capital Rennes, which is also the regional capital.) There are three languages spoken in Brittany: French, of course, Breton, a Celtic language, and Gallo, which is a form of early Northern French - langues d'oïl - and is spoken, as might be expected, in the eastern part of Brittany. Breton which began to die out has had a revival in recent times: it is taught as a second language in some schools and used partially by some media. The Romans called Britain, Brittania, the original source of this word coming from a word meaning cut, presumably because it is an island cut off from mainland Europe; however, they referred to Brittany as Amorica, meaning close to the sea. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire Brittany was also called Brittania but in due course became called Brittania Minor (or Little Britain) to distinguish it from Brittania Major, or in other words, from Great Britain. So the Great in Great Britain has nothing to do with being it being great no more than Little Britain (now Brittany) has anything to do with it being somehow inferior. Rather like Bunter Major and Bunter Minor, terms which will be familiar to fans of the Owl of the Remove. At the beginning of the middle ages Brittany was divided into three separate kingdoms which were then united into a single kingdom under Nominoe (king 845-857). Subsequently the Kingdom of Brittany reached its maximum extent extending into what are now adjacent départements, only to be reduced again by severe Viking attacks. In 937. Allan II of Brittany - with the support of Athelstan, the first king of England - expelled the Vikings and recreated a strong state. Allan paid homage to Louis IV ⁻2 of France so that Brittany ceased to be a kingdom and became a duchy. Breton lords helped William the Conqueror invade England and were given large estates there as a reward. However the Dukes of Brittany were often independent, allying with either the French or the English as best suited their own particular purpose. |

| The Breton War of Succession, which was itself a

localized

part of the Hundred Years' War between England and France, was fought

between the House of Blois (backed by France) and the House of Montford

(backed by England). The House of Montford triumphed in 1364 and enjoyed

independence until the end of the Hundred Years' War. The eventual

failure of the English as the Hundred Years' War drew to a close led to

Breton commanders playing key roles in the defeat of the English in the

final battles. The war ended in 1453 with victory to the French and

only Calais remained in English hands. ⁻2 Allan II 'Allan Twisted Beard (Varveck in Breton) and Louis IV (Louis from Overseas) were closely allied as both had been exiles in England as the courts of Kind Edward the Elder of Wessex (son of Alfred the Great) and his son Athelstan because of internal disruption ins their kingdoms. Louis IV's mother was a daughter of Edward the Elder. |

|

The Breton

War of Succession also known as The War of the Two Jeannes |

The

Dukes of Brittany had both historical and ancestral connections

with England: there were marriages between members of English

and Breton families and the Dukes were also Earls of Richmond in

Yorkshire.

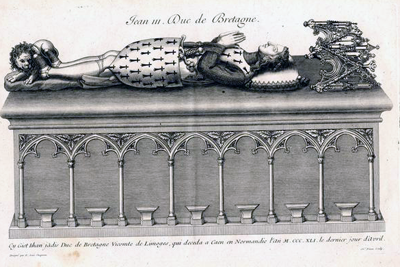

Arthur II, Duke of Brittany (left) (d. 1312) married twice: his first wife was

Mary of Limoges and his second wife, Yolande of Dreux,

Countess of Montford. By Mary he had three children: his

successor, John (d. 1341); Guy, Count of

Penthievre (d. 1331); and Peter, Lord of Dol-Comborg

and Sant-Marlon (d. 1312). By his second wife he

had one son, John de Montfort, and five

daughters: Beatrice, Joanne, and Alice, who all married into French

noble families; Blance, who died young; The

Dukes of Brittany had both historical and ancestral connections

with England: there were marriages between members of English

and Breton families and the Dukes were also Earls of Richmond in

Yorkshire.

Arthur II, Duke of Brittany (left) (d. 1312) married twice: his first wife was

Mary of Limoges and his second wife, Yolande of Dreux,

Countess of Montford. By Mary he had three children: his

successor, John (d. 1341); Guy, Count of

Penthievre (d. 1331); and Peter, Lord of Dol-Comborg

and Sant-Marlon (d. 1312). By his second wife he

had one son, John de Montfort, and five

daughters: Beatrice, Joanne, and Alice, who all married into French

noble families; Blance, who died young;  and

Marie, who became a nun. and

Marie, who became a nun.On the death of Duke Arthur his eldest son became duke as John III. (right) John III married three times but none of these marriages produced any children. He strongly disliked the children of his father's second marriage and for many years attempted to obtained an annulment of this marriage so bastardizing his half siblings. His heir of choice was Jeanne de Pethièvre -2, who was his neice, being the daughter of his younger brother Guy (now dead), and who had married Charles of Blois (below right), a nephew of the French king, Philip VI. However in due course - and for no known reason - he became reconciled to the situation and declared his only half brother - John de Montfort- as his successor, his two younger full brothers having pre-deceased him. The laws of succession in Brittany were unclear but Jonathan Sumption suggests that John de Montford, being the closest male relative, was the true heir in this rather unclear case. -1 Whatever the legal situation when Duke John III died in 1341, having governed the Duchy for nearly thirty years, The War of Succession began. Most of the nobles supported Charles of Blois but John de Montfort acted quickly, soon taking possession of the Breton capital, Nantes, and in less than four months held two other major cities, Rennes and Vannes and most of the Duchy. John was enterprising and quick witted but on the other hand he was also politically naive: however his wife, Jeanne of Flanders, a sister of the Count of Flanders, was a very capable leader and probably the architect of her husband's initial success. This would in all probability have remained a local matter but the Hundred Years' War had broken out between England and France four years earlier in 1337, although at this point there was a truce between Edward III of England and Philip VI of France which was due to expire in June 1362. John de Montfort had received agents from England and when Philip VI learned of this France accepted Charles of Blois as the official candidate. John de Montfort, whatever were his original intentions, accepted Edward III as King of France, which  was what the Hundred Years' War was all

about. was what the Hundred Years' War was all

about. At the Battle of Champtoceaux and the subsequent attempt to reach Nantes John de Montfort's much smaller army was overwhelmed by the Charles of Blois and the French forces. He was forced to surrender and was granted a safe conduct to Paris to negotiate with Philip VI. This meeting came to nothing and John was imprisoned in the Louvre. His wife - Jeanne of Flanders - now became the leader of the de Montfort cause; she is also referred to Jeanne de Montfort. Edward III was not able to aid John de Montfort because of the terms of the aforementioned treaty with France; however there was nothing in this treaty to prevent Philip VI invading Brittany to deal with a rebellious vassal. However in the new year the treaty was to expire.  Jeanne

of Flanders (left with her

husband) set up her headquarters in Hennebont in Western

Brittany where her two year old son was declared nominal head of

the Montfort party. She appointed Amaury de Clisson as his

guardian. The latter was dispatched to England with part of the

ducal treasury, which was still in Jeanne's possession. At some point

she moved her headquarters to Brest

where she was visited by a member of the rival party, Henry de Malestroit , who also happened

to be the brother of Jeanne's military commander. She negotiated

a truce with Henry which froze the military situation,

allowing her effective control of Western Brittany until the

date on which the English, under command of

the Earl of

Northampton, were expected to arrive. The advanced guard to

secure the landing places under

Sir Walter Mauny arrived

eventually after delays caused by the usual

organizational problems. The main army under the Earl of

Northampton and Robert of Artois was also subject to delays but

these was due to

diplomatic problems between King Edward and his Low Countries

allies not chaotic organization. Jeanne

of Flanders (left with her

husband) set up her headquarters in Hennebont in Western

Brittany where her two year old son was declared nominal head of

the Montfort party. She appointed Amaury de Clisson as his

guardian. The latter was dispatched to England with part of the

ducal treasury, which was still in Jeanne's possession. At some point

she moved her headquarters to Brest

where she was visited by a member of the rival party, Henry de Malestroit , who also happened

to be the brother of Jeanne's military commander. She negotiated

a truce with Henry which froze the military situation,

allowing her effective control of Western Brittany until the

date on which the English, under command of

the Earl of

Northampton, were expected to arrive. The advanced guard to

secure the landing places under

Sir Walter Mauny arrived

eventually after delays caused by the usual

organizational problems. The main army under the Earl of

Northampton and Robert of Artois was also subject to delays but

these was due to

diplomatic problems between King Edward and his Low Countries

allies not chaotic organization.Because of the build up of English troops in Southern England and before the local truce between Jeanne de Montfort and the French expired, the French attacked under the leadership of Charles de Blois, the later so that Philip VI still wished to preserve the truce, at least nominally. Charles quickly took Rennes, which was too far from the from the main Montfortist areas to be defended, and almost all of the Montfortists in Eastern Brittany submitted. At this point the advanced guard under Walter Mauny -3 (below right) arrived at Brest; he had been ordered not to attack any French forces and contented himself with a number of plundering raids. However when the main English force had not arrived by the end of June, he proposed a truce to Charles de Blois until November, that is the end of the campaigning season. He was back in England in July to lodge his prisoners in safety. Charles of Blois arrived before Hennebont in May 1342, to be met with fierce resistance, the town and castle remaining staunchly loyal to Jeanne de Montfort. The French attempted to assault the town before the army was ready resulting in a massacre and humiliating defeat. Charles de Blois's camp was  set

on fire and Jeanne herself was seen mounted on her charger

rallying her troops. A small detachment of Spanish remained at

the town but by late June they abandoned the siege and withdrew.

To the East, Vannes also held out. Charles himself, with the

main body of his army, moved to Auray while detachments roamed

the roads killing and looting. However by the end of July, with

still no English army arriving but major French forces being

redeployed in Brittany, both of these places capitulated and

Jeanne fled to Brest where by mid August she found herself

besieged by a major French force.

set

on fire and Jeanne herself was seen mounted on her charger

rallying her troops. A small detachment of Spanish remained at

the town but by late June they abandoned the siege and withdrew.

To the East, Vannes also held out. Charles himself, with the

main body of his army, moved to Auray while detachments roamed

the roads killing and looting. However by the end of July, with

still no English army arriving but major French forces being

redeployed in Brittany, both of these places capitulated and

Jeanne fled to Brest where by mid August she found herself

besieged by a major French force.The main English expedition force consisted of three armies: the first under William Bohum, Earl of Northampton, who was to be appointed the King's lieutenant in Brittany and France; the second under the King himself with the Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick; and the third under Hugh Audley, Earl of Gloucester and Laurence Hastings, Earl of Pembroke. There was also a fourth force under Sir Oliver Ingham, already in France, and Hugh Despenser (son of the executed Despenser the Younger); their pupose was to be deployed in Gascony to draw for as many of the French forces from Brittany. However Despenser remained in Brittany to reinforce Jeanne's garrison.  On 18th August Northampton's

(left!)

army arrived at Brest, the French

sea blockade proving ineffective; Charles de Blois then retreated

with his army believing that the number of the English were

greater than they actually were. Shortly afterwards Robert of

Artois returned with reinforcements. Northampton then marched to Morlaix,

thirty miles north of Brest, On 18th August Northampton's

(left!)

army arrived at Brest, the French

sea blockade proving ineffective; Charles de Blois then retreated

with his army believing that the number of the English were

greater than they actually were. Shortly afterwards Robert of

Artois returned with reinforcements. Northampton then marched to Morlaix,

thirty miles north of Brest, but

unfortunately for him the French were prepared and repulsed his

attack; Northampton settled down to a long siege.

but

unfortunately for him the French were prepared and repulsed his

attack; Northampton settled down to a long siege.The French believed, misinterpreting intelligence they had received, that the second division under the King was bound for Calais not Brest, so they withdrew a large contingent of their army from Brittany to the north and to the advantage o f Northampton. Charles of Blois withdrew his men from Guingamp, where they were stationed, and marched to relieve Morlais; however, Northampton was aware of this and marched his army through the night attacking the French who suffered heavy causalities the following morning. Morlais was thus never relieved but neither was it taken. .png) King Edward finally reached Brest on 26th October after three

weeks of gales in the Channel. The next stage in the campaign was to

recapture Vannes so a reconnoitering expedition was carried

under the command of Walter Mauny . The army began to leave Brest on

November 7th, being followed along the Breton coast by the fleet.

Unfortunately half the fleet mutinied and sailed away, the rest

being put under command of the reckless

Robert of Artois

(left). The

latter tried to take Vannes without waiting for the main army to

arrive and in this venture he was nearly successful. However Robert was wounded and,

although this was not fatal, he contracted and died of

dysentery.

King Edward finally reached Brest on 26th October after three

weeks of gales in the Channel. The next stage in the campaign was to

recapture Vannes so a reconnoitering expedition was carried

under the command of Walter Mauny . The army began to leave Brest on

November 7th, being followed along the Breton coast by the fleet.

Unfortunately half the fleet mutinied and sailed away, the rest

being put under command of the reckless

Robert of Artois

(left). The

latter tried to take Vannes without waiting for the main army to

arrive and in this venture he was nearly successful. However Robert was wounded and,

although this was not fatal, he contracted and died of

dysentery. Edward's army marched towards Vannes, all main towns on the way opening their gates to him. Unfortunately more ships sailed away and, because of this lack of shipping, the King could transport no siege engines in his advance. On 29th the army reached their objective but Vannes was ready and Edward's assault failed. However the army was kept busy: by the end of November Edward had captured three towns, including Ploërmel, the other commanders attacking the countryside around Nantes. In mid December another army - that commanded by the Earl of Salisbury - arrived in North-East Brittany burning the suburbs of Dinan and the surrounding villages. The third army under command of the Earls of Gloucester and Pembroke were driven ashore by gales and only the two earls and their personal retinue reached Brittany. It was now decided in England that the weather was now too bad to attempt any further expeditions and a new army under command of the Earls of Arundel and Huntingdonshire was planned to sail rather optimistically from March 1433. When the news of Edward's landing reached Paris at the beginning of November 1342, the French mustered a fresh army under command of the King's son, John, Duke of Normandy, This army reached Nantes around Christmas just in time to prevent a faction in that town, who were later hanged, surrendering to Warwick, who was so forced to return to the main army around Vannes. The French army moved along the inland road recapturing several towns on the way, including Ploërmel; here they stopped so that the two armies were now eighteen miles apart but yet again avoided battle. In January a truce was concluded at the Priory of Mary Magdalene at Malestroit, a truce that was favourable to King Edward. The status quo of control of the divided Brittany was  to be

maintain and John de Montfort was finally to be released from

the Louvre. Edward was not given control of Vannes: instead it was

to be held by a papal delegation until the truce expired on 29th

September 1346 and then handed over to the French King. This

long truce was to give time for satisfactory negotiations to

take place. However not all went according to these favourable

results: John de Montfort was not released from his confinement

in the Louvre and, Joanne, who had done so much for her

husband's cause, went mad shortly after she returned to England

with King Edward. She was kept in confinement in Tickhill castle

in Yorkshire, where she survived more than thirty years Her

young children were lodged in a suit contracted specially for

them in the Tower of London. to be

maintain and John de Montfort was finally to be released from

the Louvre. Edward was not given control of Vannes: instead it was

to be held by a papal delegation until the truce expired on 29th

September 1346 and then handed over to the French King. This

long truce was to give time for satisfactory negotiations to

take place. However not all went according to these favourable

results: John de Montfort was not released from his confinement

in the Louvre and, Joanne, who had done so much for her

husband's cause, went mad shortly after she returned to England

with King Edward. She was kept in confinement in Tickhill castle

in Yorkshire, where she survived more than thirty years Her

young children were lodged in a suit contracted specially for

them in the Tower of London. |

| -1 Jonathan Sumption, The Hundred Years Way. Vol 1 (Faber and Faber, 1990) Chapter XI. -2 Note that the effigy shown in the Wikipedia entry for Jeanne de Pethièvre is incorrect, it being that of a different woman of the same same. The one shown is an effigy, now in the Louvre, of Joanne (de Commynes), wife of René de Bosse, Count of Pethièvre, who died in 1514. -3 Walter Manny was buried in the Charterhouse London, but only a fragment of his tomb remains. There is no effigy. |

| ~To Be Continued~ |

| All About Anne of Brittany | ||||

In 1485 after the death of Louis XI, 'The Universal Spider' (top left), and during the minority of his son Charles VIII 'The Affable', France was ruled by a regent, Anne de Beaujeu (top right), the late King's sister. In what came to be known as the Mad War, a coalition of feudal lords, including  François II, Duke

of Brittany with aid from the Empire

and the kingdoms of England and Castile-Leon, attempted to depose Anne,

who must have been quite a formidable lady as she succeeded in breaking

the revolt without a major battle. A truce was agreed in 1485 but a

second phase of the rebellion broke out when the truce expired: this was

regarded as a Franco-Breton war between France and François

II of Brittany. This rebellion again ended in failure with

the defeat of François at the Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier.

Peace was restored with the Treaty of Sablé being signed in 1488. In this François acknowledged the French

king as overlord, but the clause that interests us here is the one

specifying that the Duke

would need the permission of the French King for the marriage of his daughters.

François II, Duke

of Brittany with aid from the Empire

and the kingdoms of England and Castile-Leon, attempted to depose Anne,

who must have been quite a formidable lady as she succeeded in breaking

the revolt without a major battle. A truce was agreed in 1485 but a

second phase of the rebellion broke out when the truce expired: this was

regarded as a Franco-Breton war between France and François

II of Brittany. This rebellion again ended in failure with

the defeat of François at the Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier.

Peace was restored with the Treaty of Sablé being signed in 1488. In this François acknowledged the French

king as overlord, but the clause that interests us here is the one

specifying that the Duke

would need the permission of the French King for the marriage of his daughters.

François had made his daughter Anne of Brittany ⁻¹ (mid left) promise never to subjugate Brittany to France. He died a few months after the Treaty of Sablé was signed as a result of a fall from his horse when Anne was eleven years old. In 1490, Anne now being thirteen was married by proxy to Maximilian of Austria (mid right), the future Holy Roman Emperor; Maximilian was of the Hapsburg family whose holdings included not only the Holy Roman (German)  Empire but

Burgundy, the Low Countries and lands in the Iberian peninsula. This

certainly kept Anne's promise to her father but it not only broke the

terms of the Treaty of Sablé but also would have surrounded France by

her enemies, and was thus quite unacceptable to the Regent, Anne de

Beaujeu. Empire but

Burgundy, the Low Countries and lands in the Iberian peninsula. This

certainly kept Anne's promise to her father but it not only broke the

terms of the Treaty of Sablé but also would have surrounded France by

her enemies, and was thus quite unacceptable to the Regent, Anne de

Beaujeu.  King Charles VIII (left), now twenty-one, took his army into Brittany and laid siege and soon captured Anne of Brittany's stronghold Rennes. Maximilian, preoccupied with affairs in the Empire did nothing. Anne now agreed to marry King Charles and they were subsequently married in 1491 in an elaborate ceremony on the banks of the Loire at Langeais, although the marriage was of dubious validity. One of the terms of the marriage contract was that if Charles were to died before Anne and if the had not produced a male heir, then she was to marry the next king of France. In fact Charles did die first by, it is reported, hitting his head on a low door lintel, at the early age of twenty-seven in 1498; and they had not produced a male heir although Anne, in one of her seven pregnancies, had given birth to only one surviving child, a son who died of measles at the age of three. The next king of France was Charles's cousin, Louis XII 'The Father of the People', a popular king (bottom right) whom Anne, according to  the marriage contract married

⁻². This

marriage produced nine children of which only two survived, both

daughters, one of whom is important to our narrative here.

Anne died in 1515 aged only 37 and before her the marriage contract married

⁻². This

marriage produced nine children of which only two survived, both

daughters, one of whom is important to our narrative here.

Anne died in 1515 aged only 37 and before her husband . The surviving daughter was

Claude, who

on her mother Anne's death, became Duchess of Brittany, and four months

later married her cousin

François,

Duke of Valois. He was heir to the French throne, being then the nearest

male relative of Louis XII. If Louis XII did not produce a male

heir form his third marriage to Mary Tudor, the sister of HenryVIII of

England, then François would succeed to the throne. He did not and

François succeeded to the throne and again a Duchess of Brittany became

Queen of France. François and Claude had seven children but only two

lived past the age of thirty. Claude died young at only twenty-four and

was succeeded in Brittany by her eldest son the Dauphin François who

became Duke François III. He died childless and then, Henry, the second

son of Louis XII and Claude became both Dauphin and Duke of Brittany; he

eventually succeeded to the throne as Henry II.

husband . The surviving daughter was

Claude, who

on her mother Anne's death, became Duchess of Brittany, and four months

later married her cousin

François,

Duke of Valois. He was heir to the French throne, being then the nearest

male relative of Louis XII. If Louis XII did not produce a male

heir form his third marriage to Mary Tudor, the sister of HenryVIII of

England, then François would succeed to the throne. He did not and

François succeeded to the throne and again a Duchess of Brittany became

Queen of France. François and Claude had seven children but only two

lived past the age of thirty. Claude died young at only twenty-four and

was succeeded in Brittany by her eldest son the Dauphin François who

became Duke François III. He died childless and then, Henry, the second

son of Louis XII and Claude became both Dauphin and Duke of Brittany; he

eventually succeeded to the throne as Henry II.At the revolution Brittany was abolished as a province of France - although hardly as a cultural and geographical entity or as a people - and was divided into five départements. The five départements remained until in 1956 the region of Brittany was created out of four and that takes us to where we began.

|

||||

| ⁻¹ Anne had been initially promised to King

Edward V, one of the 'Princes in the Tower'; it might be interesting

(although entirely futile) to speculate the future course of history if this boy

king had survived. ⁻² Louis XII, as Louis of Oléans, had been forced by Louis XI to marry the latter's daughter Joan who was deformed and sterile. This was a cynical attempt by the King to extinguish the Orléans cadet branch of the Valois dynasty. Louis XII, when he became king, had this marriage annulled by the Pope so that he could marry Anne. Joan later founded a monastic order. |

||||