|

HAUTE-LOIRE |

|

La Chaise-Dieu (Le Monastier-sur-Gazeille) Le Puy-en-Velay Saint-Flour

|

La

Chaise-Dieu Abbey of La Chaise Dieu |

| Although La Chaise Dieu would seem

to translate as The Chair of God, the name is

said to be

from the Occitan Chasa Dieu, meaning The House of God;

this itself is from the Latin Casa Dei.

The Auvergne

is a spectacular mountainous region of France and La Chaise

Dieu is 3,500 feet above sea level. Unfortunately the town is

very much a tourist destination with crowds milling around and

all; the abbey church is similar with the 'all' being a very

long winded and loud tour guide whose voice reverberates around

the church. Photography is difficult, partly because of the

relatively dark interior (photography is allowed but, because of

the wall paintings, flash is understandably not) and partly because of the

aforementioned

crowds. There are several free car parks in the town and entry to the church is also free. Guided tours (not recommended) may be paid for at the Tourist Office next door to the church. Ref: 45°19.27N, 3°41.73'E |

|

|

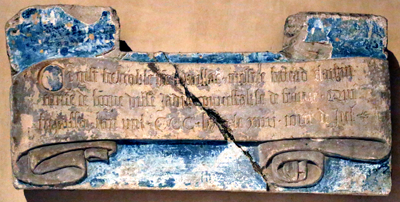

All left and above: An unknown 13th century abbot or a Bishop of le Puy. Limestone discovered in 1999 during work on the Abbey. The effigy is continuous with the underlying slab but the tomb chest is a modern replacement (not shown) |

|

|

|

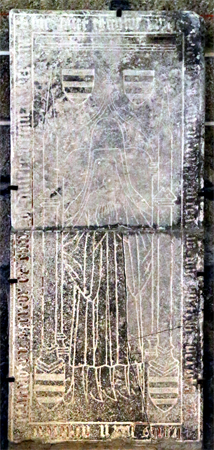

All left and above: Smaragde de Vichy Wife of Maurion de Touzel Stone, 15th Century |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nicholas de Beaufort,

Archbishop of Rouen 1342-47 Uncle of Pope Clément VI Marble effigy of 14th Century on sandstone tomb chest, which does not seem to belong |

|

|

|

|

| Pope Clément VI (1352) Marble, 14th Century |

||

| Born as Pierre Roger in the Limousin in

1391, the future pope entered the Benedictine Abbey at

Chaise-Dieu in 1301. He received a first class education and was

appointed to a number of increasingly important ecclesiastical

positions, including that of Abbot of Féchamp, when he unsuccessfully

summoned Edward III to France to pay homage to Philip VI for the

Duchy of Aquitaine, and Archbishop of Rouen in 1330. He was

elected pope as Clément VI in 1342, becoming the fourth of the

Avignon Popes . He resisted secular encroachment on ecclesiastical jurisdiction and lavishly increased papal splendour. It was during his papacy that the Black Death first arrived in Europe. He died at Avignon and was buried there temporarily, his body being later translated to Chaise-Dieu. |

|

|

| Above:

This looks like a base to a sarcophagus,

together with carved stone pillow and drain hole at the bottom.

The sides are very low and appear finished. No explanation is

given. Right: Unnamed monument with tomb chest with weepers and a fine canopy. Fragments of wall paintings under the arch. |

|

Le

Monastier-sur-Gazielle Church of St. Théophrède |

Parking is free near the church; the church is open. The List reports there is a 15th century effigy of canon or a bishop of Puy in the church. The church notes confirm this and tell us that it is situated against the east wall of the church, presumably in the ambulatory. We could not find any effigy in any position in the church. We visited the Office of Tourism, which is next to the church, and were told that the effigy is [now] in the sacristy which is locked and open only on Sundays. It was not Sunday when we visited the town. The person on duty at the Office of Tourism could (or would) not arrange to open the sacristy for us. I did find the rather poor photograph below on the internet, which I believe is from the site of the above office. |

| Ref: 45°56.30'N, 3°59.9'E |

|

| Le Puy-en-Velay |

The Cathedral is built on the highest point of the City although there are two even higher points, nearby: on one is situated a the Chapel of St Michel d'Aigilhe, built in 969 and reached by 268 steps cut into the rock; nearer on another outcrop is the iron statue of Notre-Dame de France, which was designed by Jean-Marie Bonnassiex and cast from 213 Russian cannons taken at the Siege of Sevastopol (1854-55). The statue was presented to the city in 1860. Le-Puy-en-Velay was one of the principal starting points in France for the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Adhemar of Le Puy (1045-1098) was bishop here: he was appointed papal legate and was one of the leaders of the First Crusade, but died at Antioch before Jerusalem was taken. We had planned to visit the Cathedral and the Church of St Laurent. We had some difficulty parking, although we eventually found a car park in the lower part of the City; the Church of St Laurent was, by chance, on the corner. The parking charges are relatively modest. There was a good and modestly priced brasserie on the edge of the car park. |

|

|

Church of St Laurent |

| St Laurent, as mentioned, is in the lower part of the City. The church is open, entry is free and photography allowed, but the interior is rather dark. |

|

|

|

Monument of Bertrand du Guesclin (1320) covering his entrails (see below) The Church of St Laurent was the church of the Convent of the Dominicans -1 Above top is the recumbent effigy. To the right is preserved the epitaph (shown above bottom), which is on the rear wall of what, I understand, is the restored original canopied tomb in the north chapel. To the left is the effigy now under a new arch in the chancel. |

|

-1 The Dominicans are also known as the 'Jacobins' in France, and the 'Blackfriars' in England. |

|

|

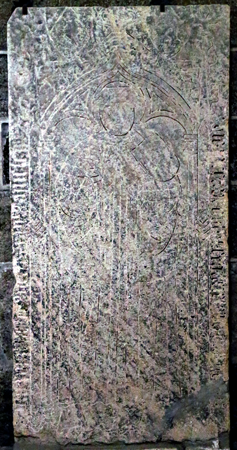

| Bernard de Montaigu Bishop of Puy 1237 |

Fragment of leger stone dated 1773 Now clamped to north wall of nave |

| Bertrand de Guesclin (c.1320-1380) |

| Bertrand du Guesclin was born near Dinan in Brittany of minor Breton nobility, the Lords of Broons. He was a French military commander during the first part of the Hundred Years War and was Constable of France -1 for King Charles V (known as 'The Wise') from 1370 until his death. * He initially served in Brittany under Charles of Blois (who was supported by the French) in the Breton War of Succession. (1341-1364); this was effectively a part of the Hundred Years' War. Charles's rival for the Duchy was John de Montford, who was supported by the English. Interestingly another John, Sir John Chandos, a man similar background to du Guesclin, fought in the English army; du Guesclin himself was knighted for his military skill during this Breton campaign. His success in Brittany restored the French morale after their disastrous defeat at Poitiers, where their King, John II (known as 'The Good'), had been captured. His successes in Brittany brought him to the notice of the future King Charles V ('The Wise') of France. When Charles became King he sent du Guesclin to deal with Charles II ('The Bad'), King of Navarre in his attempt to secure his claim on the Duchy of Burgundy, which Charles had hoped to grant to his brother Philip, the future Philip the Bold. There was a peace treaty between England and France at this time - the Treaty of Brétigny (1360) - so the English soldiers supporting Charles the Bad were drawn from the mercenary routiers rather that Edward III's army, to avoid breaking this treaty. This treaty had been signed when King John was still a prisoners and the French morale at a low ebb because of thecapture of King John and on going conflicts in Paris between the future Charles the Wise and the forces of Étienne Marcel as well as the outbreak of the peasants revolt, known as the Jacquerie. In 1364 Navarrese army under Jean de Grailly, the Captal de Buch, a Gascon noble and military leader, met the French forces at Cocherel and were defeated, the Captal de Buch being taken prisoner. Apart from the Navarrese action the Treaty of Brétigny might have seen to be the end of the Hundred Years' War but in 1369 Charles the Wise, now king, declared war on the English again on the pretext the King Edward III had broken the terms of the peace treaty. Later that Bertrand du Guesclin was himself taken prisoner when the army of Charles of Blois was heavily defeated at the Battle of Auray by John IV, Duke of Brittany, son of John of Montford - 2, one of the original two claimants to the Dukedom. The English contingent was led by Sir John Chandos, and Charles of Blois was killed in the action. Du Guesclin was in due course ransomed by King Charles V. This battle ended the Breton war of Succession. King Charles 'The Wise' requested du Guesclin to rid France of the Free Companies who had been pillaging France since the lull in the war resulting from the Treaty of Brétigny. Du Guesclin persuaded the captains on the Free Companies to join him in an expedition to Castile to aid the bastard Henry of Trastamára ('the Fratricide') against his legitimate half brother, Pedro I ('the Cruel'), King of Castile. Henry the Fratricide granted du Guesclin the County of Trastamára and the Kingdom of Granada, a somewhat worthless gesture as these were yet to be conquered from the Muslim Nastrids. This was soon to be undone: Edward, the Black Prince, led his army into Castile in 1367 in support of Pedro and met Henry's army at Nájera, where the latter was defeated and Pedro ascended the throne of Castile. Du Guesclin was captured once more (by the Captal de Buch) but once more ransomed. However this was to be a pyrrhic victory for the Black Prince and a final turning point in his life: four out of five of his men died during the campaign and the Black Prince himself became ill, an illness from which he never recovered. It also left him in a disastrous financial situal, Pedro failing to honour his debts. However two years later, in 1369, Henry and du Guesclin were back in Castile and defeated Pedro at the Battle of Montiel; Pedro took refuge in the Castle of Montiel where he bribed du Guesclin to let him escape, which he did. However Pedro had been tricked as Henry paid du Guesclin a higher fee to being his half brother before him. When the half brothers met Henry murdered Pedro by stabbing him several times - thus earning his sobriquet. This victory sealed the Franco-Castilian alliance and du Guesclin was made Duke of Molina. The war between England and France had now restarted and du Guesclin was recalled from Castile by King Charles who made him Constable. This title was normally held by a nobleman and it is said that the Constable, who came from a relatively humble background, experienced some difficulty in getting the more aristocratic leaders to serve under him, a situation similar to that experienced by Sir John Chandos. The English fortunes were now at a low ebb: Edward III's abilities were declining, his son, the Black Prince, was suffering from increasingly poor health and several of the former able captains were now dead or in prison. Du Guesclin was successful in several battles against the English and progressively the English were to lose all of the territories ceded to them by the Treaty of Brétigny, including Poitou. Bertrand do Guesclin was to take part in active fighting for another ten years: his death is described below. He was known as 'The Eagle of Brittany' or 'The Black Dog of Brocéliande'. Brocéliande was a legendary enchanted forest, found mostly in Arthurian Tales - 1 The Constable of France was one of the original five great officers of the crown. He was Commander-in-Chief of the army, effectively Lietenant General to the King, outranking all other nobles. - 2 Sometimes John of Montford is confusingly known as John IV of Brittany and his son John as John V of Brittany. |

| The Four

Burials of Bertrand du Guesclin A Tale of Four Cities |

||||||||

The town of Châteauneuf-de-Randon, Lozère (former region

Languedoc-Roussillon), which had been held by the English,

surrendered to the besieging French army under the command of

Bertrand de Guesclin on 4th July 1380. However du Guesclin died

shortly after this surrender on Friday 13th July of, it seems,

natural causes at about the age of sixty. He appears to have developed

hyperthermia fighting in hot and humid weather and then

died of surfeit of iced water; or perhaps it was a form

of dysentery. Before his death he had dictated

his will stating that he wished to be buried in his native

Brittany, in the Church of the Jacobins at Dinan, where his

ancestors were interred. The town of Châteauneuf-de-Randon, Lozère (former region

Languedoc-Roussillon), which had been held by the English,

surrendered to the besieging French army under the command of

Bertrand de Guesclin on 4th July 1380. However du Guesclin died

shortly after this surrender on Friday 13th July of, it seems,

natural causes at about the age of sixty. He appears to have developed

hyperthermia fighting in hot and humid weather and then

died of surfeit of iced water; or perhaps it was a form

of dysentery. Before his death he had dictated

his will stating that he wished to be buried in his native

Brittany, in the Church of the Jacobins at Dinan, where his

ancestors were interred.Dinan is a long journey from Châteauneuf-de-Randon - a distance of a little over 500 miles - so it was essential, especially in the summer heat, to embalm the Constable's body. This was carried out at the Convent of the Jacobins were the viscera, including the brain, were removed, from the body. These organs were buried at the church of the Convent, St Laurent, where there was a funeral service on the 23rd July. However, Olivier de Mauny, the former close companion of du Guesclin, and the funeral procession had already left Put-en-Velay, for, on the 18th July they arrived at Clermont-Ferrand, where it was found that the Constable's body was beginning to decay despite the embalming. It was therefore decided to separate the soft tissues (the 'flesh') from the bony skeleton, so, at the Dominican Convent of Montferrand (a suburb of the city), the body was boiled in a cauldron to effect this process. The soft tissues were buried there with a second funeral service and then the procession continued on its way but now only carrying the Constable's bones and heart . He was honoured with ceremonies, and even funeral services, in all the towns and cities that his remains passed through, as well as elsewhere, on their long journey to the north. It is not known if a monument were constructed over the site of the burial of the soft tissues at Montferrand as there appears appears to be no drawing or other record of such a construction, althoug it is likely. The procession crossed the Loire at Angers and then letters arrived from the King requesting that du Guesclin's body be buried in the Basilica of St Denis at the foot of the tomb that King Charles had prepared for himself in the chapel of St John the Baptist, a rare honour. The King was to die two months after the Constable. The route to Brittany was abandoned and the procession headed towards Chartres and then, avoiding the crowds in Paris, directly to town of St Denis and it basilica, now a suburb of Paris. The casket containing the Constable's heart continued on its journey to Dinan where it was buried beneath a slab of granite painted black with an incised inscription in gold  lettering. Below the inscription was the arms of the Du Guesclin

family, below this a heart, and then below this the arms of

Bertrand himself,

who belonged to a cadet branch of the Du Guesclin family. So

only the heart of the Constable came to rest where he had wished

his body to lie.

lettering. Below the inscription was the arms of the Du Guesclin

family, below this a heart, and then below this the arms of

Bertrand himself,

who belonged to a cadet branch of the Du Guesclin family. So

only the heart of the Constable came to rest where he had wished

his body to lie.In 1890 the heart in its casket and the slab were transferred to the Church of St Saviour, also at Dinan. See photograph above left. The inscription reads:

At St Denis the construction of the tomb was entrusted to Thomas Privé and Robert Loisel under the direction of the King's master mason, Raymond du Temple. It was not completed until 1397. The monument  consisted of an

alabaster effigy with a gablette over the head and a greyhound at

the feet; these lay on a black marble slab with an inscription

in gold lettering, although this is not clear from the drawing. Only the effigy remains today and this has

undergone a number of restorations. From the drawing the tomb chest appeared to

be quite plain except for the shield of arms at the foot and an

inscription on the gablette. According to contemporaries it

is an excellent likeness of the Constable, who was not a

physically attractive man. See photograph right. consisted of an

alabaster effigy with a gablette over the head and a greyhound at

the feet; these lay on a black marble slab with an inscription

in gold lettering, although this is not clear from the drawing. Only the effigy remains today and this has

undergone a number of restorations. From the drawing the tomb chest appeared to

be quite plain except for the shield of arms at the foot and an

inscription on the gablette. According to contemporaries it

is an excellent likeness of the Constable, who was not a

physically attractive man. See photograph right.The monument at Puy-en-Velay is similar to that at St Denis although it is not know who constructed it. It consists of a recumbent effigy on a paneled tomb chest set into a niche. The gablette and greyhound are in this case intact. The back of the niche was painted with a banner bearing the inscription:

The dismembering of bodies is rather a distasteful subject and some requested in their wills that their bodies must not be subjected to this process after their death. It was certainly frowned upon by several popes. It did perform a necessary hygienic function when someone, like du Guesclin himself, died a long way from where they wished to be buried and in a time when embalming was not a particularly effective process. It later appeared to have served a more ritualistic function rather than just a practical one: so that more of the earthly remains would receive prayers on the spot, as it were. It is interesting to note, and this must given an idea of the attitudes of the time, the inscriptions on the monument mentions the heart but not the entrails or skeleton. It is probably for practical reasons that the skeleton was buried in the most prestigious of places, not that this is considered the most important part of the body. On August 1560 the Church of St Laurent, which was outside the city walls, was pillaged by the Huguenots and the monument badly damaged. On September 21st 1800, during the Consulate, the prefect of Haut-Loire announced a project to commemorate the anniversary of the Republic: the casket containing the remains of du Guesclin were to be removed from St Laurent and placed in a column that was planned to celebrate the heroes of France. The column was never constructed but the casket was removed from the church and kept in the marie: it was returned in 1908. At this time the decayed monument was enclosed behind a wooden screen but could still be viewed. The then parish priest, a Father Eynac, took the initiative to restore the monument and a subsidy was obtained for this purpose. The monument was temporarily moved to a south chapel (St Anne's Chapel) for this work to be done. This restoration was carried out by a sculptor, a M. Crouzet, to excellent effect so it is said. Where possible all the original broken parts were reassembled and new work added by obtaining information from old drawings (of which I have not found copies) of the tomb. It is said that the features were accurately portrayed since the restorers were in possession of a 'mould', although it quite unclear to what this actually refers; it is likely that this was a death mask which were certainly taken of the deceased at this time. The monument was then moved to what was then intended to be its final (although not original) site, the north chapel, adjacent to the chancel. In 1955 major restorations were carried out on the church and it then became possible to return the monument to what appears to have been its original place in the south side of the chancel so that it faced the monument to Bernard de Montaigu on the opposite (south side). The monument was so transferred in 1966 to what is described as its original position and where it may be seen today. It was placed under a new, modern arch although the original arch may still be seen in the north chapel. - 1 Note the name is given as Guaquin in Dinan but as Claikin in Puy-en-Velay. The date of death also differs: it is 13th July in Dinan and the 14th July in Puy-en-Velay. The July 14th date is the generally accepted one. †††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††† What Can Be Seen Today 1. The tomb at Puy-en-Velay was damaged during the Wars of Religion and again during the Revolution. It was later restored and may be seen today. 2. The Dominican Convent of Montferrent at Clermont-Ferrand and any monument were destroyed during the revolution and nothing remains. 3. The monument at St Denis is described above, and in the St Denis pages, may be seen today. 4. The heart burial was transferred to St Savior in Dinan, the slab being set upright in a pillar with the presumably casket, of uncertain date, on top. But that was not all..... A number of statues to Bertrand du Guesclin have been constructed over the years but these do not come within the scope of these articles. It appears that he was considered to be a French hero, as the manner of Joan of Arc was to become; however it must be remembered that in du Guesclin's time France was not the single united country it is today. Two of these monuments may be of interest. A cenotaph was built to du Guesclin in 1828 at the site where it is believed that his tent had stood when he died at of Siege of Châteauneuf-de-Randon. An effigy of blue limestone, a copy of that at St Denis, was placed in the mausoleum. (see directly below) This structure was replaced by a granite mausoleum in 1911. (see below left) The original effigy was replaced by one of zinc by sculptor Phillippe Kaeppeli in 1980. (see below right) The original limestone effigy is preserved in the du Guesclin Museum in the town.

A statue to du Guesclin at Broons, Brittany, was destroyed by the Breton Liberation Front in 1977, because, as he was allied to France, he was considered a traitor to Brittany. |

||||||||

| Cathedral of Notre Dame of the Annunciation | |

| The Cathedral is a steep climb up a number

of streets and then there are one hundred and thirty seven steps

(in total) to reach the west door of the Cathedral. It appears to be

possible to drive some of the way at least to the Cathedral and

the steps can be circumvented by a steep, but somewhat easier,

walk to the south transept along the streets. Entry to the

cathedral is free and photography is allowed. The 'List' refers to five recumbent effigies in the cathedral: one is medieval (under the bell tower) and the other of the 19th century. There are photographs of both of these in the 'The List' but not of the other three which are referred to are medieval, but we could not find these; however there are a number of incised slabs in the chapter house, now clamped to the wall and these are shown below. There is a charge to enter the cloisters and the chapter house but photography is allowed. |

|

Above far left and centre: Bishop Pierre IX Marc le Breton (1886) Bishop of Puy-en-Velay. Above right: Unknown bishop of Puy. 15th century. Lower row far left: Canon Jean de Brun (1342) Sandstone. Lower row near left: Monument of a canon. 14-15th centuries. Note: The 'List' note fives monuments in the Cathedral but we were only able to discover four of them, Bishop le Breton. The guide in the cloisters told us that there were no other monuments. However searching the internet gave three of the missing four. These are all used for permitted purposes. That of Canon le Brun is by FélixMartin-Sabon taken before 1907 and held the Ministry of Culture. The missing one is of Mathelin des Chazens (14th century), unless I have misidentified one of those above. Canon le Brun is certainly correct, although the list states there to be a gisant present. These 'missing' monuments all appear to be in the bell tower. The fourth monument mentioned above may be an error as the French Wikipedia entry list only three: two canons and a bishop |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

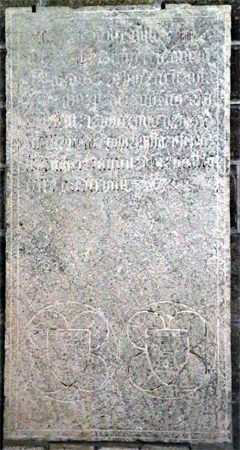

The Cathedral was staffed by Secular Canons who were buried, as was the custom, in the chapter house. Their stones have now been set around the wall to prevent further wear. Most have incised effigies, inscriptions and arms. Right: Part of a monument now in the cloister. I was unable to read the brass. |

|

|

|