|

COUNTY DURHAM |

|

|

Aycliffe

Barnard Castle

Brancepeth

Chester-le-Street <Durham City> <County Durham - 2> <County Durham - 3> |

|

Aycliffe - St Andrew |

|

|

Waiting for Image |

There are a number of cross shafts and heads as well as grave covers in the church Note the upside down figure in number three above |

| Frederick Richard Hardinge (1856) Mate of HMS Encounter Died of dysentry aboard RN Hospital Ship Hercules at 24 |

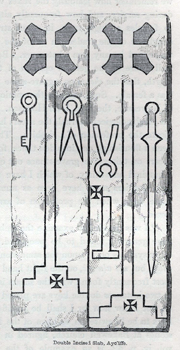

'The Farrier's Gravestone' Now no longer in situ and buried under the carpet. Grave cover of a blacksmith and his wife. Note the key and shears for a woman. And the hammer, tongs and sword for a blacksmith. |

Priest |

|

| Sandstone knight c. 1300 |

| Other Monuments |

| George Chapman JP (1932)

and his wife, Margaret (1925) Brass Charles John Aylmer Eade Vicar 1880-1926) and his son, Aylmer (1917) KIA Poelcapelle, Belgium at 25 Brass |

| Barnard Castle - St Mary |

|

| Robert de Northam Vicar of Gainford. Mid 14th century. |

A number of medieval foliated crossed preserved in the church. Note some of the symbols carved which include a sword and sheep shears. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Far left:Hon Sir John

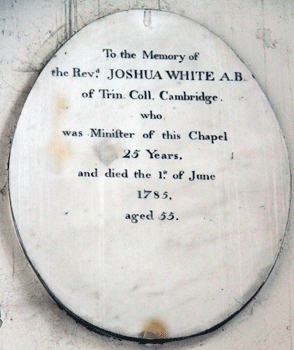

Hullock (1829) Knight & Baron of the Exchequer Above left: Thomas Colpitts (1799); his wife Ann (1816); their 2nd daughter Ann (1808) ; their sons: Thomas (1819), John (1812), George 1810). Added below is their daughter Eleanor (1841) Centre Left: Rev Joshua White A B (1783) 'Minister of the Chapel 25 years' Above right: Dame Mary Hullock (1856) widow of Sir John Far right: Rev Robert Barnes (1801) |

||||

| we received a very warm and helpful reception from members of the staff at St Mary's, Barnard Castle. |

|

Brancepeth - St Brandon |

| St Brandon's suffered a disastrous fire during the night of September 16th 1998 leaving little more than a shell Virtually all of the fine woodwork was lost; however a curious archeological discovery was made, which is described below. Restoration of the church began almost at once and this was completed in 2014. |

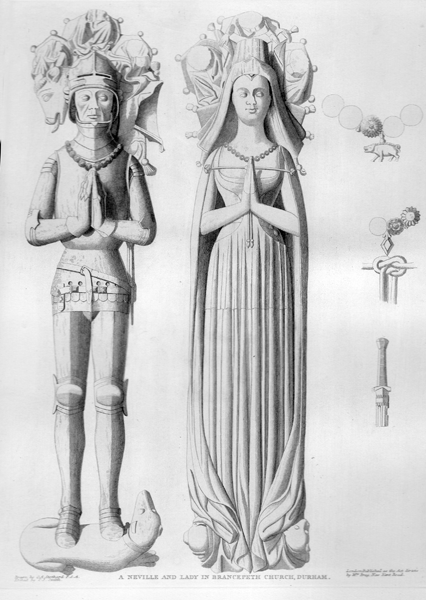

These effigies were of wood and unfortunately destroyed in the fire mentioned above. |

|

Ralph Neville, 2nd Earl of Westmorland (1484) and his wife, Elizabeth (Percy) (1440) |

|

| Ralph Neville became heir apparent to Ralph, the First Earl, when his father died in France in 1440; his grandfather,

the First Earl, died in 1445 and then Ralph succeeded to

the earldom. However the First Earl had settled much of his

inheritance on his second wife

Joan Beaufort and their twelve children; she was one of the

four illegitimate children of John of Gaunt and his mistress

Kathryn Swynford, who were legitimized bu act of parliament following

their parents subsequent marriage. The family was now very well

connected to the royal and other powerful and influential families.

This inheritance gave rise to the

Neville-Neville feud which at times became violent. All of these twelve children gained property, titles and offices: for example Richard, the eldest, became Earl of Salisbury while Robert, the youngest, eventually became Bishop of Durham. Ralph spent much of his life trying to regain his lost inheritance but Joan Beauford had powerful allies such as her brother Cardinal Henry and Thomas Langley, Bishop of Durham, who was to be succeeded by one of her sons, as mentioned. The First Earl had also strictly followed the law in his decision on this inheritance. Although a settlement was reached in 1443, it was really a failure for Ralph Neville: he did regain Barony of Raby but he had to concede most of his lands to the Earl of Salisbury. Ralph raised troops for the Lancastrian side in the War of the Roses but did not take a major part if the fighting as by this time he had 'succumbed to mental disorder.' He was then under the guardianship of his brother Sir Thomas, who died in 1458 and John was killed at the Battle of Towton in 1461. Ralph's second wife was Margaret Cobham, 4th Baroness Cobham. He was succeeded by his nephew, another Ralph, as the Third Earl, his two children having died young. |

|

|

|

|

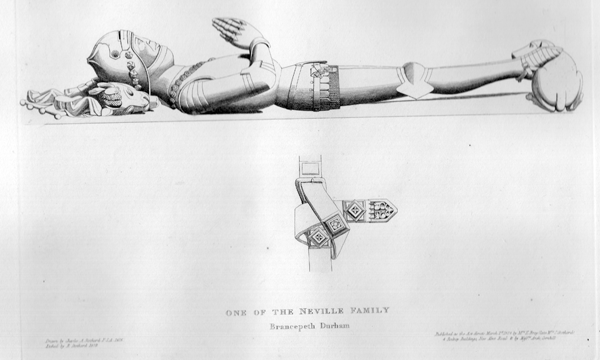

| Above: Sir Robert

Neville (1319) known as, because of his swaggering

ways, as he Peacock of the North. He was the eldest son of Ranulph, First Baron Neville of Raby, but, because he predeceased his father, his elder brother, Ralph, the victor of Neville's Cross, inherited the barony. He fought at the Battle of Bannockburn and married Ellen Neville of Raby. This was a time when the Scots were making numerous border raids into England and Sir Robert was killed during one of these outside Berwick in single combat with Sir James 'The Good' Earl of Douglas, also known as Black Douglas. The monument was damaged in the fire and the yellow stains are of molten metal falling on the stonework from the roof. |

| Ralph Neville, 3rd Earl of Westmorland (1523) |

| I do not have a photograph of this monument,

which was a large stone tomb chest without an effigy. I do not

yet know if it survived the fire. Ralph Neville was the only child of John, Baron Neville, brother of the unfortunate Second Earl, by his wife Anne Holland, daughter of John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter. John was killed fighting for the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton in 1461 and attainded later that year. However his son, Ralph, obtained a reversal of this attainder and became 3rd Earl of Westmorland and Baron Neville, when his uncle Ralph, the 2nd Earl, died in 1484. Ralph, the 3rd Earl, was predeceased by his son, so that his grandson became the 4th Earl. |

| d | ||

|

|

|

|

The fire mentioned above caused considerable

damage and great losses to the church. It also uncovered

over one hundred 12th to 13th century grave slabs buried in the

walls of the clerestory which were exposed when the heat from

the fire stripped off the internal covering. These were well

above the ground near the roof and regularly arranged. It is

thus speculated that these stones were 'hidden' in the walls by

the rector John Cosin, an enthusiastic builder - was was

actually responsible for the clerestory - and who later became

Bishop of Durham, in order to protect them from vandals or

'reformists'. However it must be said that gravestone are

frequently (if rather disrespectfully) reused as building

material: witness many a church yard path. The slabs feature crosses of various designs, many swords as well and a few shears. Forty have been kept in the church - see above, left and right - and the rest in Brancepeth Castle. |

|

| Lost Brasses | ||

| Thomax Claxton

1403). Knight Richard Drax (1456) Priest. Demi-figure. On each corner if the stone in which the brass are set images of the four Evangelists. |

| Modern Brass (not damaged by fire) |

| Gustavus

Russell 8th Viscount Boyne, 2nd Baron Brancepeth (1909).

Brass with simple cross above the English text and leaf

border. John Parrington (1876) Rectangular but a gothick arch surrounds the Latin text. Floral design. Gustavus William, 9th Viscount Boyne, Baron Brancepeth (1942). Also his elder son Gustavus Lascelles Hamilton-Russell (1940) KIA Dunkirk, serving with the B.E.F. Edward Duncome Shafto (1879) Capt. R.A. Killed by an explosion at Bala Hissar, Carbul. Note: The H in Bala Nissar looks very much like an N but I am sure it is Bala Hissar, which means Hight Fort. |

| Chester-le-Street - St Mary & St Cuthbert |

| The Lumley Effigies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The parish church at Chester-le-Street contains a series of fourteen effigies representing members of the Lumley family, although these effigies do not mark their actual burial sites. They were arranged in the chronological order of whom they represent, or are supposed to represent, (that is, not necessarily according to the actual age of the monuments) beginning at the west end of the church with the earliest and proceeding along the north aisle to the last, when the chancel is reached. Each effigy lies on an tomb slab which itself lies on what might be called a continuous tomb chest. There is a wall tablet over each giving the name of the represented and detailed genealogical and other information. Or at least this was how they appear to have been intended to be arranged when they were installed although, as will be shown below, they were not. They were commissioned by John, Lord Lumley at the end of the 16th century to proudly demonstrate his lineage and most - but not all - date from that time; others were removed from other burial sites. Two - that of Ralph, Lord Lumley and his son Sir John - were removed by license which included the monuments and the remains from the Bishop from the church yard of Durham Cathedral in the late 16th century. However what John, Lord Lumley believed to be the burial sites - 'the lay cemetery near the north door' - was, in fact, according to the Cathedral records incorrect. It seems to be unknown from where the third 'original' effigy was removed. Some have broken feet and one the lower part of his legs; most are in a rather poor condition, although the 'genuine' monuments are far better. I must stress that I have not yet seen these monuments let alone photographed them: the photographs below were kindly sent to me by Richard Collier and I have based this short article on these photographs with information from written material which I have attempted to correlate with the photographs. Let me state first of all that the short section about these monuments in Pevsner The Buildings of England: County Durham is not only vague and confusing but also quite incorrect. For example, he states that the last monument in the series represents John, Lord Lumley (1610), the instigator of the series: it does not, but rather his grandfather, also John, Lord Lumley. Furthermore, if you examine the effigies today you will see that there is a row of only twelve effigies along the north wall of the north aisle and a further two making a separate row right back at the west end again; this may be seen in the photographs below. Pevsner writes that 'by this time the aisle was so full a second row was begun', although he does not clearly state exactly what he means by this; he had just referred to John, Lord Lumley (1610) so this seems to imply a further two monuments were inserted. In fact these two were moved from the row so that an organ could be installed in Victorian times; furthermore there have been movements of effigies and the accompanying tablets over the years and some of the latter are lost. The first table is distilled from the chapter The Parish Church of Chester-le-Street by Robert Surteen in The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham Vol 2, Chester Ward. (Nichols & Son, London 1820). I have used the list of effigies and the genealogical tables as described in that chapter, often using the (somewhat) unclear language there. The comments and deductions are mine

We can now attempt to identify the effigies as they are arranged today.

I will now give further information which is in the 1820 article and the more relevant information from: Christian D Liddy and Christian Steer, John Lord Lumley and the Creation and Commemoration of Lineage in Early Modern England (Archaeological Journal 167:1, 197-227). I will also pose some questions and attempt some answers. The effigies - were installed on the instruction of John, Baron Lumley (c. 1533-1609) in the 1590's to show a direct male line from around the time of the Norman Conquest to Baron John himself , but with gaps which will be discussed later. This Lord John was the son of George, Baron Lumley, himself the son of the John, Baron Lumley whose effigy is the last of the series described above. This George Lumley took part in the Pilgrimage of Grace, a rather a gentle euphemism for the serious year long rebellions against King Henry VIII, which took place 1536-1537 and was led by lawyer Robert Aske, after whom it is sometimes named. Lord George was attainted and executed for his part in the rebellion. He was buried in the church of the Crutched Friars in London but without a monument. Eighteenth and nineteenth century sources give a copy of his epitaph in Chester-le-Street Church, which was attached to the north wall of the north aisle but now is obscured by the organ. His son, John, consequently did not inherit the barony but petitioned the King (Edward VI, King Henry now being safely out of the way) in 1547 for restoration of the honor, which was granted. It must be said here, however, that this ancestral line, although supported on a historical basis in several texts, is considered to be dubious to say the lease and the 'imported' effigies certainly do not represent whom they are supposed to represent. It is also interesting that the acts of treason by two ancestors which led to their execution and loss of the barony are not mentioned: for example, George's epitaph merely states that he 'predeceased his father'. An agreement had been made between John, Baron Lumley and thirteen named parishioners for the preservation in perpetuity of twenty-two monuments. What exactly does this mean in this case? Monument does not necessarily refer to effigies but may also refer to wall monuments as well. There is also the likely possibility that the project was never completed and the whole twenty-two monuments were never constructed. Liddy and Steer believe that this was actually the case and that six others - to Lord John himself, his two wives and three children of his first marriage, who predeceased him - were planned; in support of this they refer to a 1805 document which mentions 'an oval left blank for some future inscription upon which are three shields of arms, namely that of John, Lord Lumley, of Jane (Fitzalan), his first wife, and of Elizabeth (Darcy), his second'. This specific wall monument at the east end of the north aisle is now totally obscured by the organ chamber. I have found over the years that these overlarge and rather unsightly instruments do have a habit of disrespectfully partially or completely obscuring church monuments, which is to be much regretted. As mentioned earlier the effigies have been moved around over the years, as have the tablets. For example a drawing in the document of 1805 shows vacancy between Sir John and Baron George, as mentioned in the 1820 article above, clearly intended for that of Baron Thomas, which was, for some unknown reason, never completed. In the same drawing the effigies of Sir Thomas (no. 12) actually lay on the ground and not on the tomb chest shelf at the extreme east end and the epitaphs of Barons Richard (no. 13) and John (no. 14) to be on the south side of the east end of north aisle with their effigies lying on the ground below them. This seems to indicate that it was some time before they were moved into their intended position. Most of the monuments are made from magnesium limestone of a poor variety that tends to flake and this has certainly happened in the case here. At one point the monuments was covered with a wash which did little good but rather caused further erosion. The two effigies from Durham (said to be Ralph, Lord Lumley and his son Sir John) are of Frosterely marble while that of William I is made of a local sandstone, although it is not known where this was taken from. The continuous tomb chest shelf is made of a sturdier sandstone. One effigy, that of Sir Marmaduke, has lost his lower legs while several have lost at least the tips of their feet. Pevsner states that Lord Lumley had to have the feet of many cut off so that all the effigies would fit in a row; this is possible for the first two as the photographic evidence shows but most appear to be accidentally broken. He also states that one (actually Sir Robert although he is not named ) 'had to have his feet on his shield'; this rather awkward statement if read as 'on a shield' would make sense as his feet do rest on a small shield which takes up less space than the usual lion. It is interesting to note that the effigies try to follow the pattern of effigies over the years: almost all the early male effigies (with the exception of clerics and kings) wear armour (and then the pattern goes - straight legs, crossed legs, straight legs again, even though the armour is not always contemporary with whom the effigy represent in several cases here); later they begin to wear civilian dress, such as merchants, lawyers but here probably parliamentary robes. This sequence is followed here with the exception of no. 12, Sir Thomas, who had been killed in battle. Liddy and Steer make the interesting conclusion that Baron John Lumley planned this series to show his family's glorious past, glossing over and not mentioning that two members had been executed for treason. His family had, following the Reformation, been excluded from public life because of their Catholicism - which, it must be pointed out, was not due to dogma but to real fear from acts such as the attempted removal of Queen Elizabeth from the throne and even her assassination - and he was looking back through decidedly rose tinted eye glasses at the good old days, which like all good old days were actually more old than good. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| The above are at the west end of the aisle

are in the back ground we can see Liulp,

Uchred and - one of the genuine effigies -

William I (c. 1260) |

|

| Above, according to the tablets, are: John, Lord Lumley (10); Richard, Lord Lumley (11) ; George, Lord Lumley (12). |

|

|

|

||

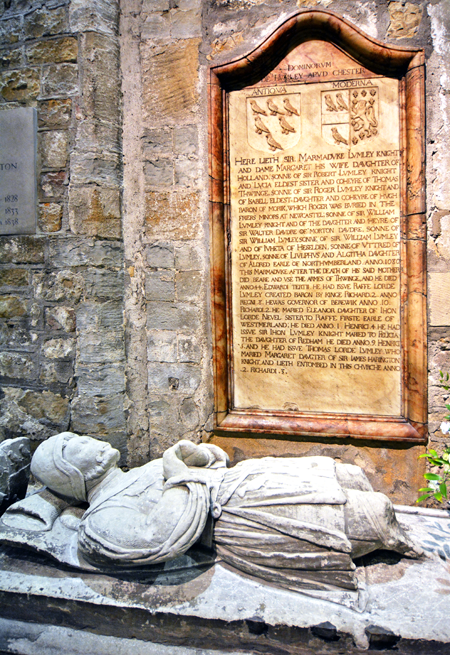

| Sir Marmaduke Lumley The lower legs have been lost |

The steel plate engravings are by Edward Blore and the etchings by Charles A Stothard